Designed by: Noor Fakih, Tom Shahar, and Julia Rose Chin

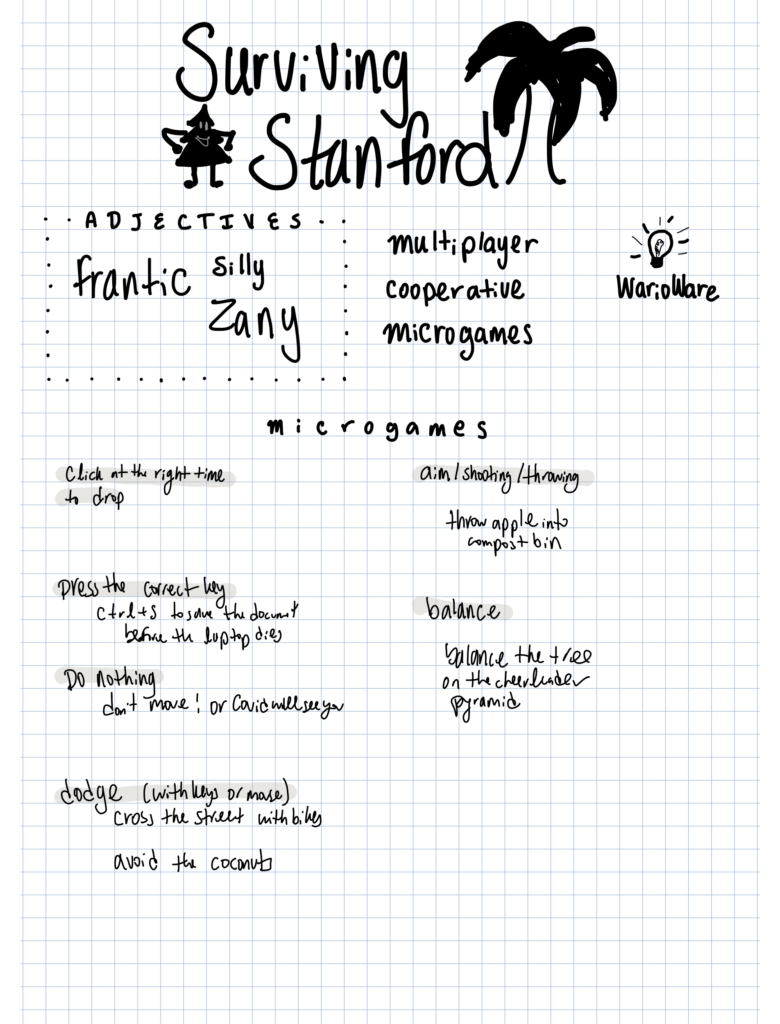

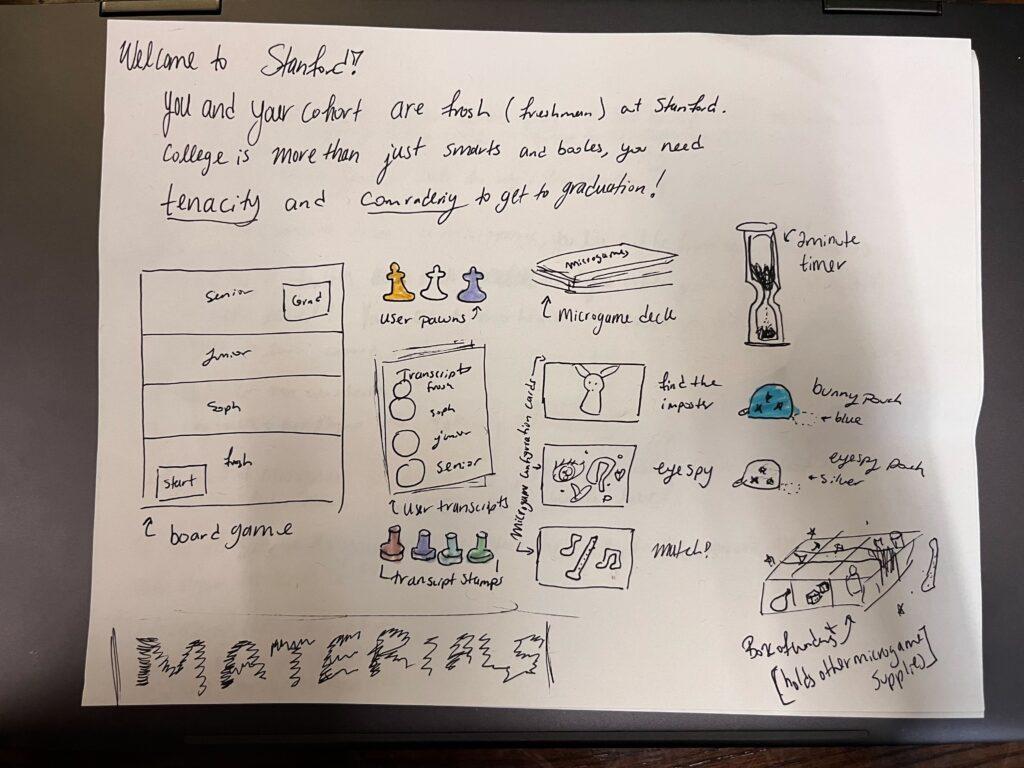

“Surviving Stanford” was inspired by WarioWare for its short, rapid-fire microgames, so we wanted to incorporate the frantic atmosphere created by this format into our party game. The entire group of 3-6 players work together to work through the different levels of microgames we’ve devised. We also found that analog and tabletop games afford a certain level of sensory pleasure, when it comes to interacting with physical objects, so to create a more intimate atmosphere within the group, we ended up creating a fully analog game that uses physical props and cards to set up the microgames. Each microgame is themed around common experiences that Stanford students and alumni will be familiar with, from Fountain Hopping to dodging bikes at the Circle of Death after classes let out. For those who are more competitively minded, we have also created a version of the rules where each person competes against the others to obtain as many cards as possible, with Mario Party-esque “bonus cards” that players can get at the very end! “Surviving Stanford” aims to break the ice between players with some lighthearted cooperative (or competitive!) minigame fun, with a fun Stanford theme.

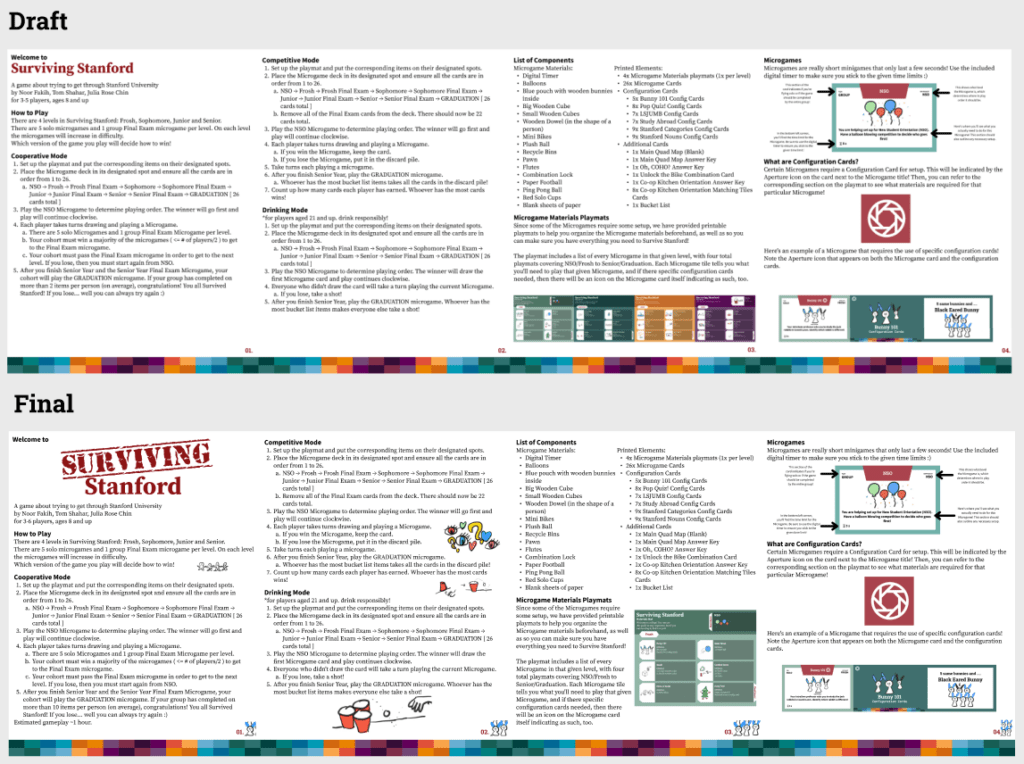

If you’d like to give the game a shot yourselves, here’s a version you can print and play yourselves at home! Do you have what it takes to Survive Stanford?

And for your downloading ease, the following attachment includes the four prior PDFs in one .zip file!

The Creation of “Surviving Stanford”

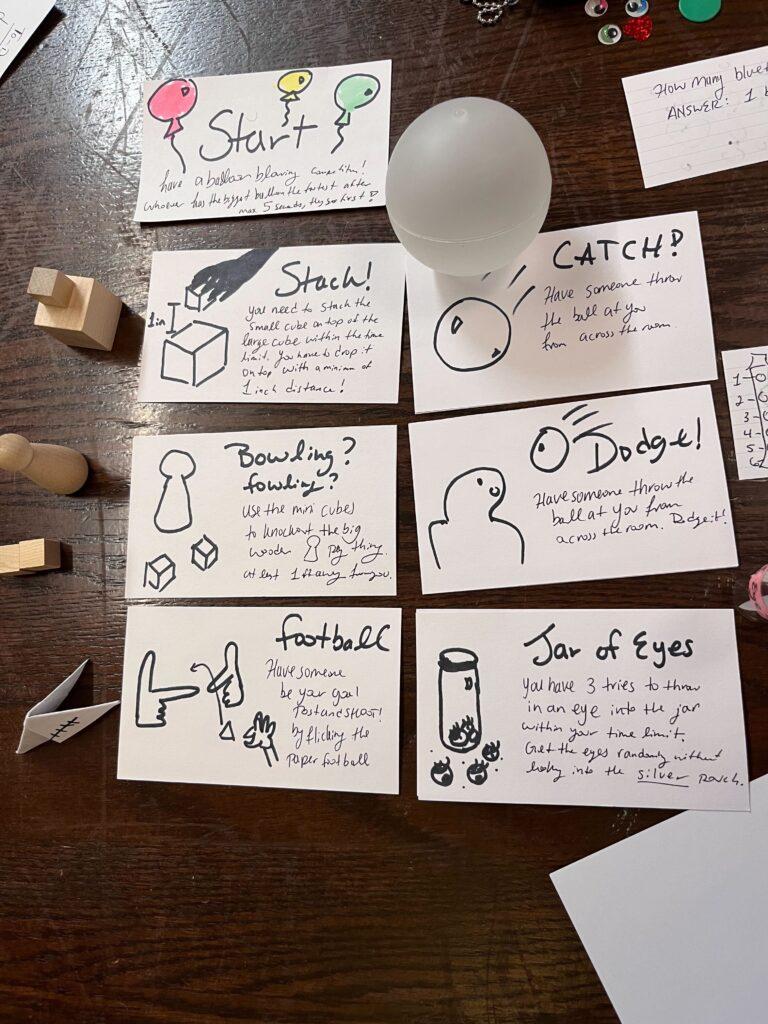

We wanted to mainly pursue a cooperative party game, since we’d seen so many other party games that pitted players against each other. Because of that, we settled on the Stanford theme – a real-world setting where peers work together to help each other graduate – to bring more flavor and a fun premise to our game. In our main (cooperative) ruleset, either everyone (or no one!) “graduates from Stanford” by completing our set of Stanford-themed microgames. This also ties into how we chose to leverage the Fellowship type of fun in our game, since players will help each other and get to know each other over the course of the game and completing the microgames. The procedures for each game are similar enough to not make the game too daunting to get into for first-time players, with clear instructions outlined on each microgame card. Additionally, since games are not too strictly defined, it allows for certain “house rules” to develop, especially for some of the “dodge” minigames where one player is actually pitted against another. In these cases, players generally still chose to throw at the player they were targeting, even though the rules don’t say so anywhere.

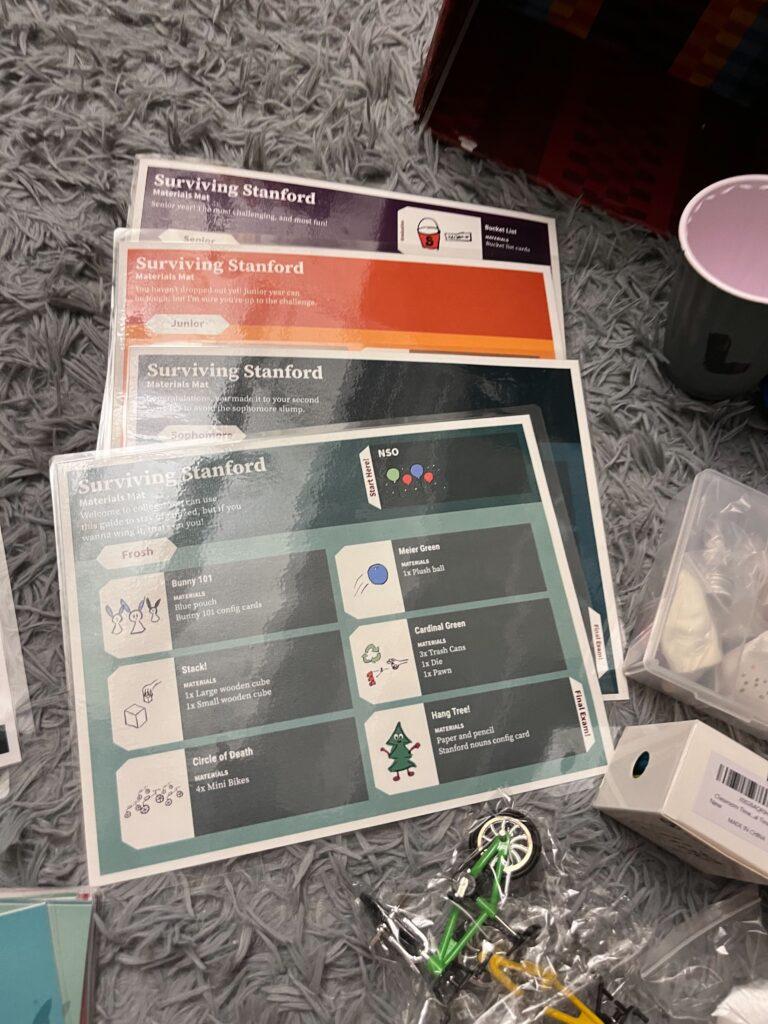

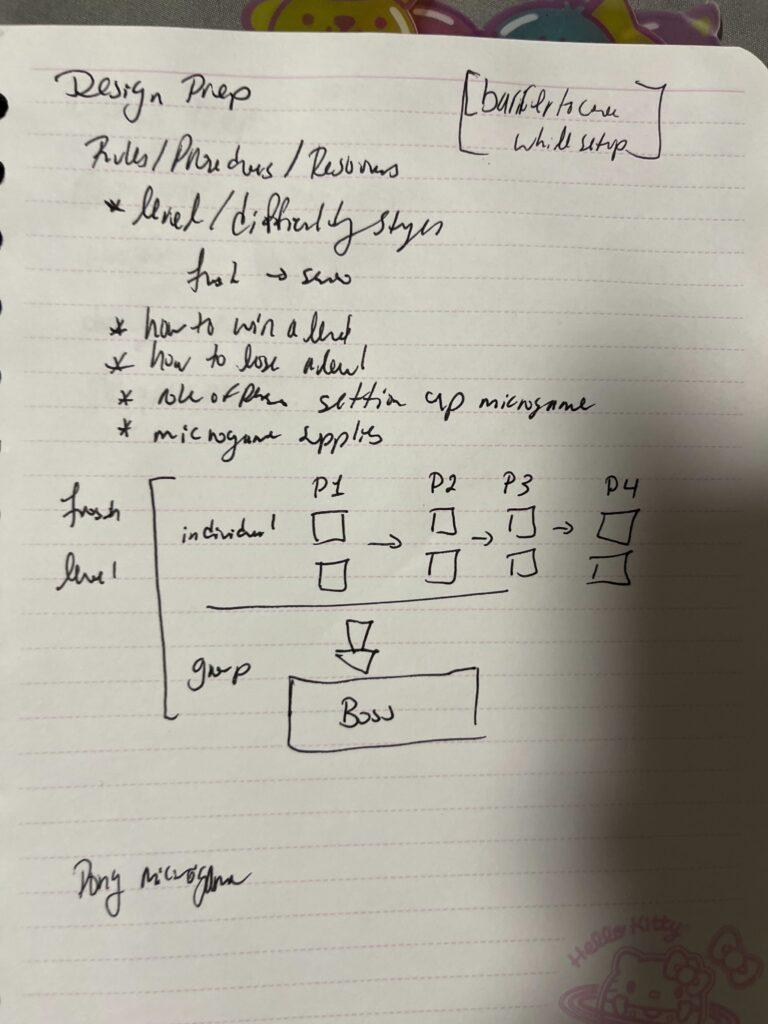

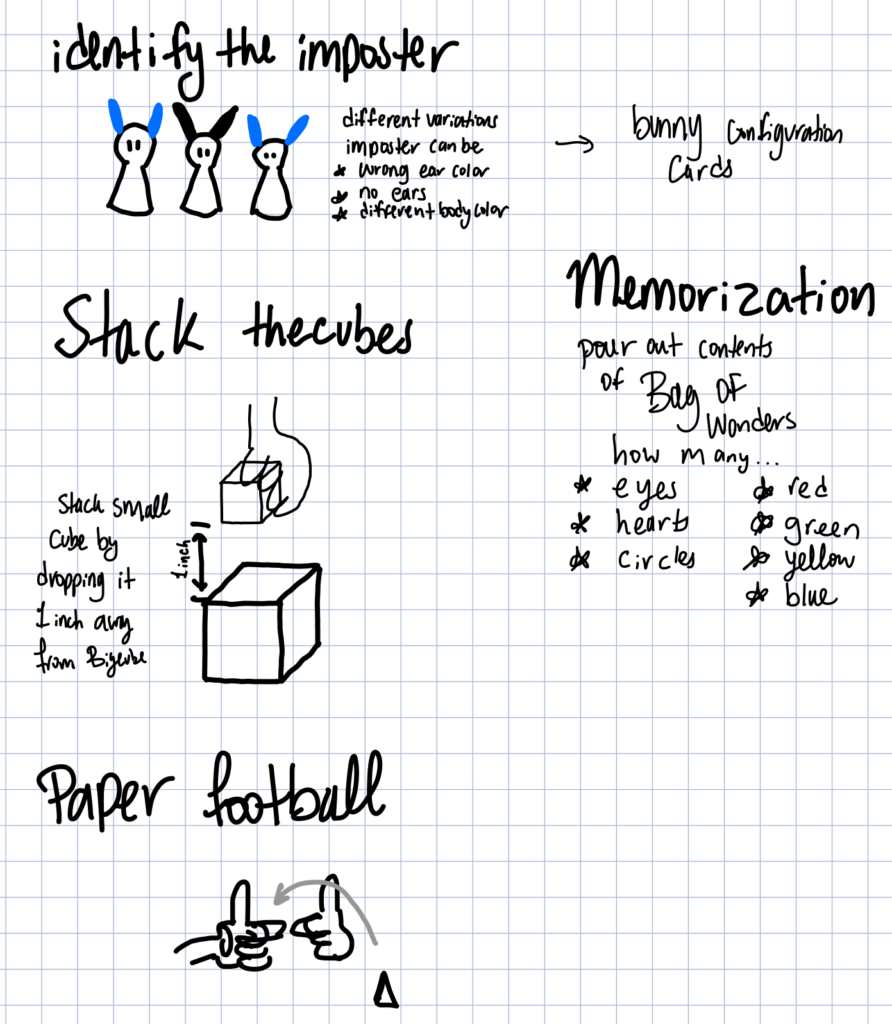

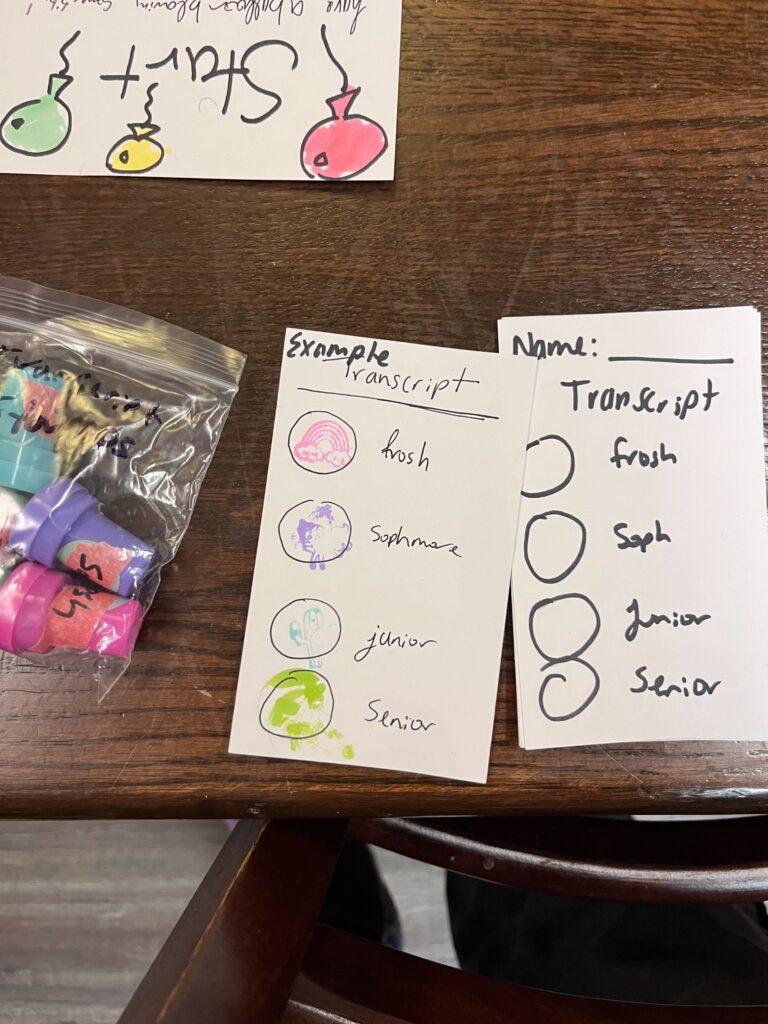

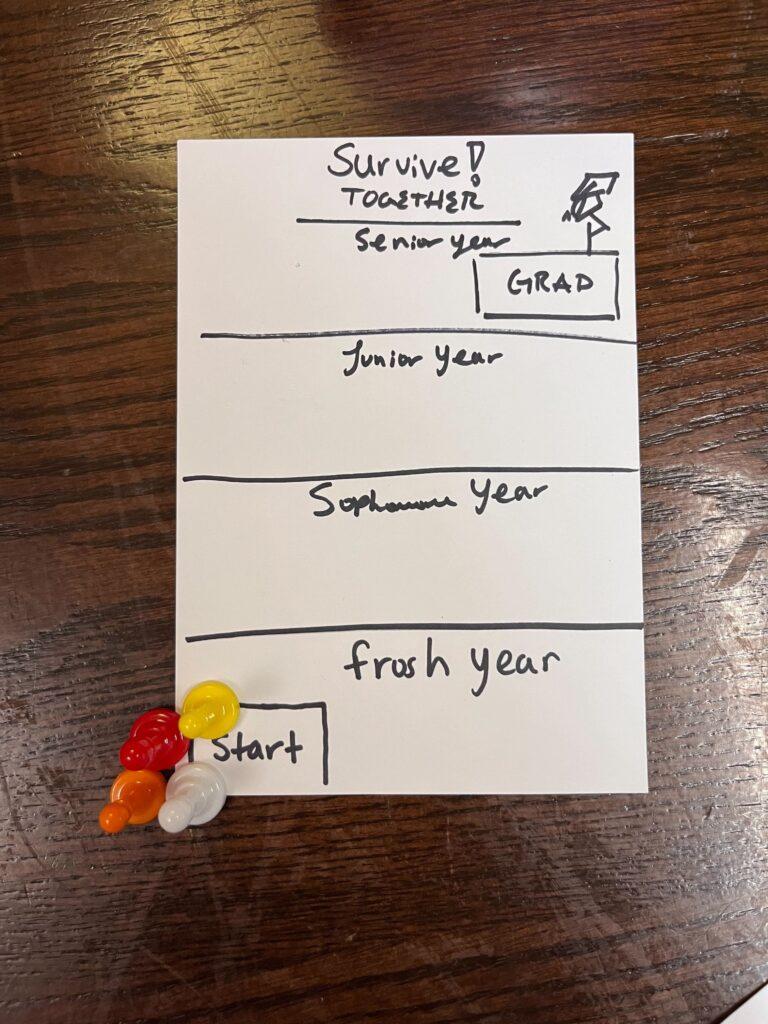

Rather than just having a random selection of microgames, we wanted to make sure each and every one was intentionally designed. As such, we brainstormed various ways to incorporate the theme of “Surviving Stanford” into our game. Even if each individual game had some Stanford-themed flavor text, we quickly realized that the games could be too disjointed and lead to a more confusing play experience, so we decided to add an overarching level structure to our game, with each level themed around a specific class year at Stanford, from NSO/Frosh year to Senior year and Graduation.

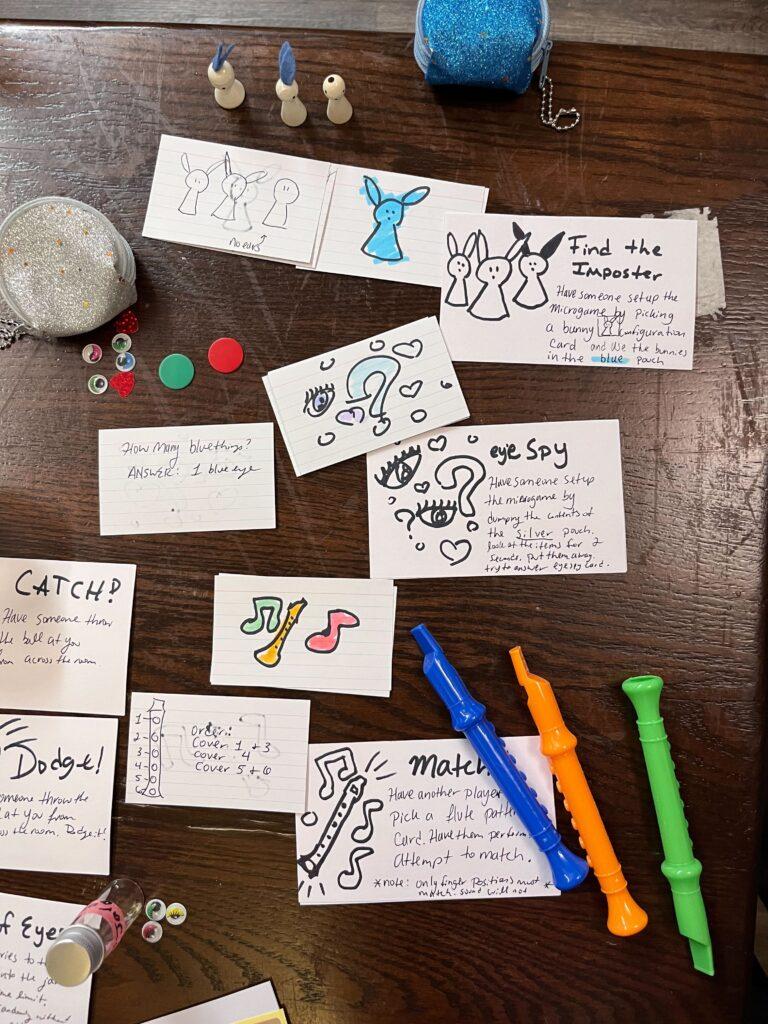

Another thing we leveraged was sense pleasure, outlined by the Sensation type of fun. We wanted to create the same type of frantic fun that WarioWare’s microgames afford, but since it’s difficult to create satisfying physical microgames that take 5 seconds or less to play out, we ended up going for longer durations of microgames, but leveraging sense pleasure to increase the fun and frantic energy in our microgames. We also agreed that physical components and cards made games played in person feel more intimate and helped players build closer relationships over the course of the collaborative gameplay.

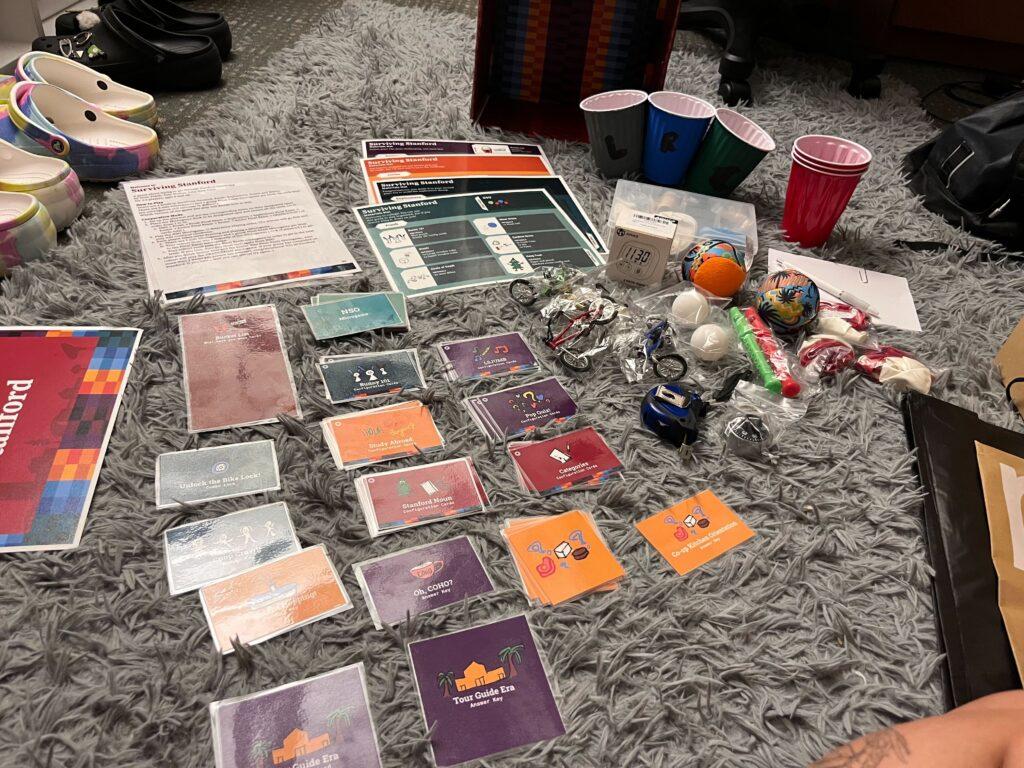

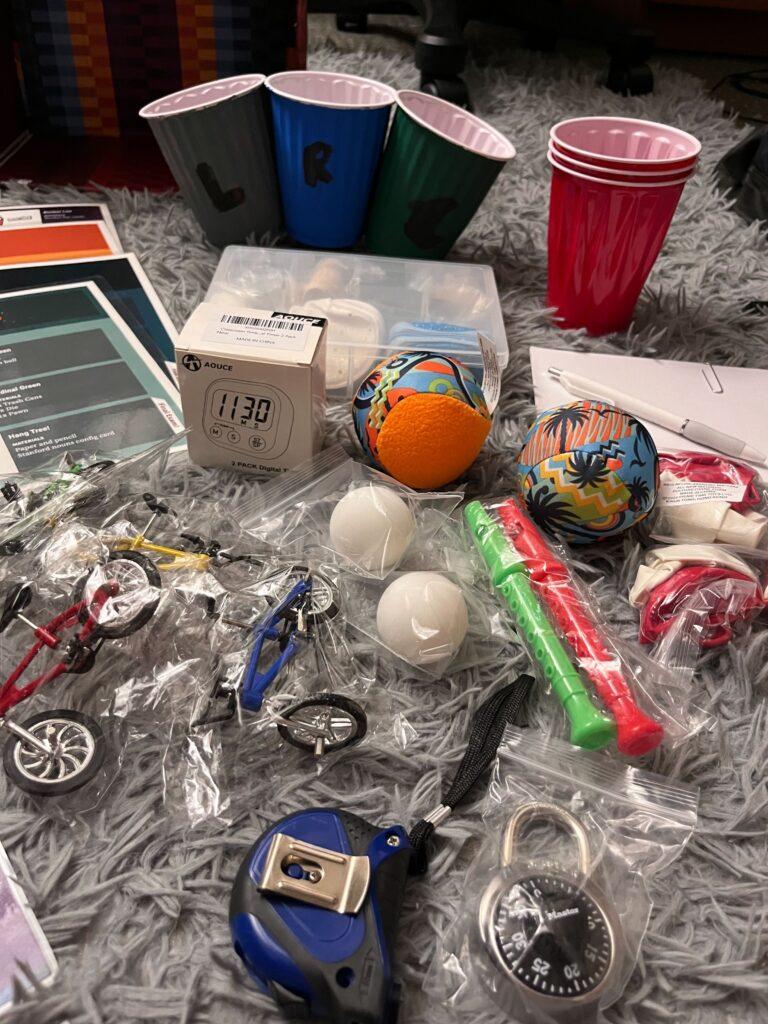

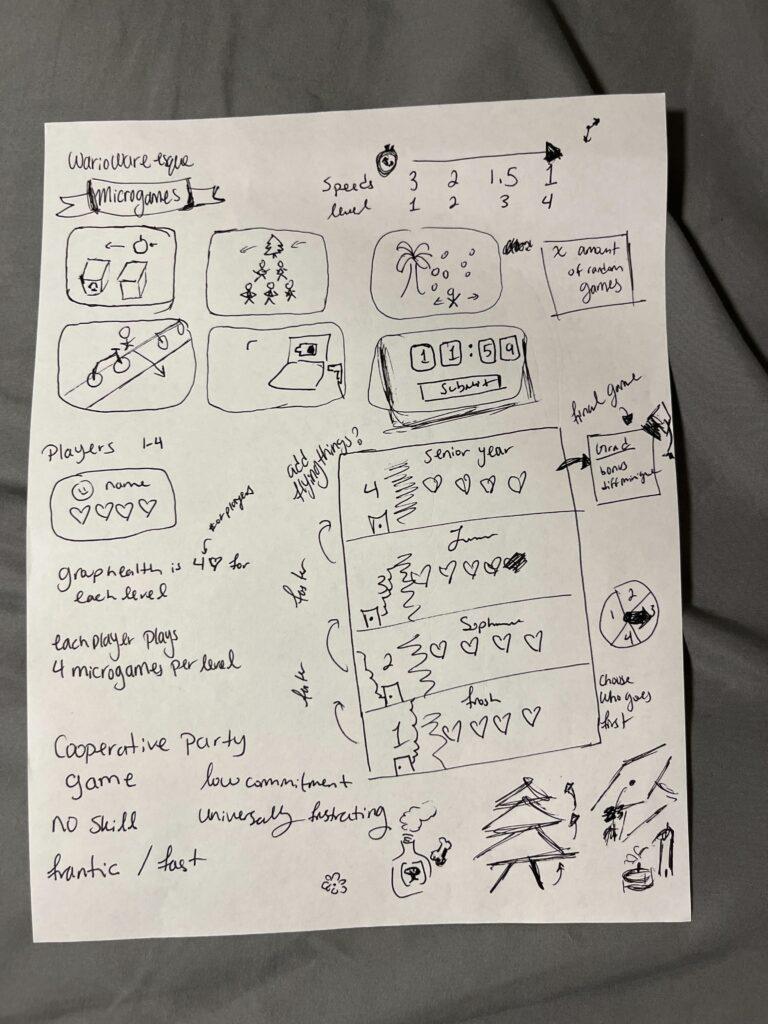

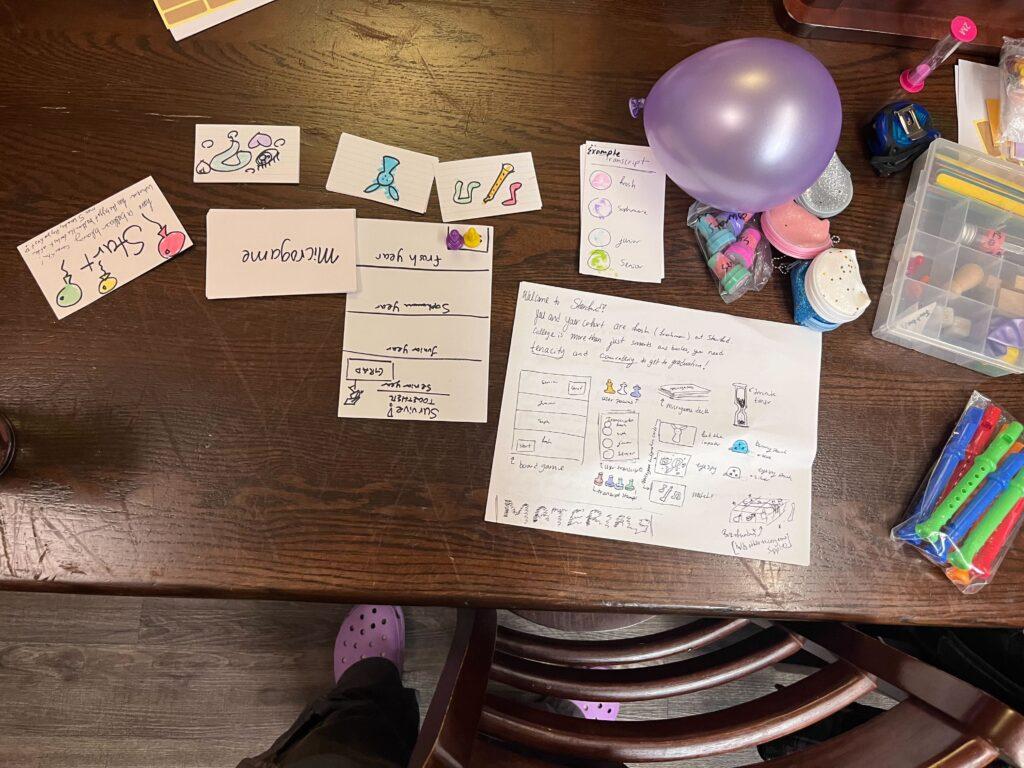

With all this in mind, we created our first physical prototype:

Given that our primary target audience is current Stanford students, we made sure to playtest among diverse groups of students, especially from those in CS 247G. These individuals, specifically, are able to give us specific feedback from the perspective of game designers, which we can take and apply actionably. We also did preliminary playtests among our own group, while we were first coming up with how we would apply the microgame format to a physical prototype and to test the balancing of our games. However, to test our game on a more diverse set of Stanford students, we also playtested multiple times with peers who were living in our dorms. Our game brought out very positive feelings about Stanford and were frequently expressed in playtests of the complete version of the game. It did well with students at any point of their Stanford career, and we saw upperclassmen teaching underclassmen about Stanford traditions or figures referenced in the game. For example, players discussed prime fountain hopping locations during Fountain Hopping!, sustainability at Stanford and Cardinal Green program during Cardinal Green, everyone’s individual experience in the Stanford Marching Band during LSJUMB, stories of being chased by jack rabbits during Bunny 101, and seniors telling their Bay to Breakers war stories. Underclassmen seemed especially intrigued by the game due to being exposed to Stanford traditions and past norms they were unaware about due to their time off-campus during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One specific concern of our playtesters was with the somewhat loose guidelines given by the microgame cards, such as, “Dodge the object being thrown at you!” We were asked what mechanism was in place to prevent interpretations of the rules where someone could say, “well, technically I did what the card told me to,” and we figured that the fun in these types of games is created by the players themselves, so if they wanted to take a less “fun” interpretation of our rules, that was on them. This can be seen in other more open-ended party games, such as Truth or Dare or Scribbl.io. If people choose to just write the word they’re given or ask “bland” truths or dares, then that isn’t in the “spirit of the game.” Through playtesting, there was usually one player per group that would try to “game the system” and go against the “spirit of the game” by playing an easier version of the microgame such as playing in short distances. These players did not “taint” the experience as a whole, since each player got to play their own microgames and they responded well to being told to play “fairly” by other players.

Something that stayed constant throughout our playtests was the visceral feelings of joy and excitement by the players as they revealed the next microgame they were to attempt. So, as we prototyped and came up with more concepts, we did our best to maintain our previous levels of quality when it came to our players’ experiences. We especially tried to take into account the specific aspects of our existing microgames that brought the most joy to our players. We noticed that interacting with physical items on the table added another sense of novelty, so we tried to leverage these props in many of our games. Our challenge was the sheer amount of props, set-up time, and creating microgames that are meant to last only a few seconds and are explained in few words that made sense to the player. To make sure our microgames were intuitive to the player, we developed them by doing random actions with our game kits and things around our dorm rooms, making sure to take note of the sensory experience. To speed up gameplay and reduce setup and the amount of instruction needed, we created material mats for the players to lay out each prop with the appropriate microgame. We decided to keep this in our final game, even though it technically added more components to our game, since we received glowing feedback about the mats: one of our playtesters specifically commented, “great job on making a seemingly complex game very accessible!”

As we continued to iterate over our original design and microgames, we decided to keep the initial “silly” sketches from our original prototype because they were true to the initial whimsical vision we had in mind for our game. We made digital versions of these sketches and added them to our final microgame cards, but to make sure this aesthetic was consistent throughout the entire game, we also changed the “Surviving Stanford” logo to be more whimsical, as well as incorporating more “microgame-style” doodles to our rule guide to match the theming and aesthetic of our other components.

And finally, here’s a video of our final playtest! It’s definitely a game that invokes a lot of laughs, smiles, and reminiscing for players at any point in their Stanford journey 🙂

Additionally, here are some photos of our final printed and laminated game materials, along with our box!