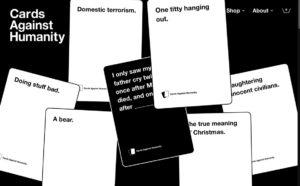

Ca rds Against Humanity is a card-based adult party game. Released in 2011, the game was created by a group of eight high school friends: Josh Dillon, Daniel Dranove, Eli Halpern, Ben Hantoot, David Munk, David Pinsof, Max Temkin, and Eliot Weinstein.

rds Against Humanity is a card-based adult party game. Released in 2011, the game was created by a group of eight high school friends: Josh Dillon, Daniel Dranove, Eli Halpern, Ben Hantoot, David Munk, David Pinsof, Max Temkin, and Eliot Weinstein.

The game itself revolves around using pre-made cards to create humorous or shocking statements, which can sometimes border on politically incorrect or risqué territory. Because of the adult themes of the game, Cards Against Humanity suggests that players are 17+ years of age, however I feel that the true target audience starts in early high school.

The game is structured around two piles of cards: the black prompt cards (ex: “What will improve the quality of life?”) and the white answer cards (ex: “Camel toe”). All players must have ten white cards at any given time, which are distributed at the start of the game. A minimum of three players is required, however there is no listed maximum (an ideal group size is often listed as 6-8 players). There are two player roles, the Card Czar and standard players, where the Card Czar role switches with each round. Each round, one player is the Card Czar (the game’s suggested method of first choosing the Czar is the “person who most recently pooped”) and draws a black card. The Czar the reads this card to the group, and then all other players submit one of their white cards face-down to the Czar. The Czar shuffles all of the answers, reads out each card combination to the group, then picks a favorite combination. During the Czar’s decision process, players can discuss and make cases for/against different white cards without having to divulge which card they submitted. Once judged, whoever submitted the winning combination gets to keep the black card. Once the black card has been awarded, all players draw white cards such that they have a total of ten, then the next round begins with a new Czar (often going clockwise around the circle). The game doesn’t have a formal end (other than running out of cards), such that the group can decide the length of the gameplay. In addition to the listed rules, the game encourages using alternate or house rules in order to keep gameplay fresh.

The game’s main types of fun seem to be fellowship and expression. Because Cards Against Humanity is a judging game, players have to inherently try to anticipate the humor and preferences of others (specifically the Card Czar), which requires getting to know their fellow player better, hence fellowship. The game also leans naturally into expression, as players must express their own humor and creativity through their card combinations.

I think that Cards Against Humanity works largely because it encourages players to be as outrageous as possible while also providing a clear structure to do so within. Players are naturally encouraged to not only think outside of the box, but also engage actively with others to try to tip the game in their favor. The slightly more mature themes of the game make it especially ideal for party settings or friend groups of medium to high levels of closeness. Additionally, by encouraging the use of alternate rules, the game presents multiple ways to keep players engaged even after becoming very familiar with the decks. In terms of improvement, the cards do tend to get old rather quickly if players have familiarity with them and are playing by house rules, which can disincentivize many sessions of playing. Perhaps most notably, the largest issue with the game that I could see arising is the content of the cards themselves. Although the game differentiates itself from other similar games (namely Apples to Apples) through its mature/risqué content, I know that there has been controversy in the past surrounding card content, especially as the game itself encourages players to be as outrageous as possible, which can easily lead to being purposefully offensive (or worse). While changes have been made to the game in the past to exclude particularly egregious cards, because this issue is so integral to the game’s concept, I think it is very hard to separate these concerns from the game itself.

Because the game itself is centered around humor and creation (as opposed to answering personal questions), the level of vulnerability needed does not seem particularly high. I think that a level of trust amongst those playing is important in order to understand that statements made do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of players, however there is not much individual vulnerability needed to play the game (unless you go all out, in which you could definitely open yourself up to criticism).