Art Heist

Creators: Will Coors, Allie Littleton, Blake Sharp, Alex Tsai

Artist’s Statement

As avid puzzlers and readers, we set out to create a game that could combine the satisfactory rush of solving a challenging crossword with the joy of becoming completely immersed in a thrilling story.

The closest we had come to experiencing this ideal balance in the past was an escape room, but we wanted to create something accessible regardless of geographical location and time constraint. From this vision, Art Heist was born.

In Art Heist, players have a chance to assume new identities as spies on a mission to track down elusive art thieves. Every puzzle or clue relates to the mission and brings the team one step closer to their goal. We even took our vision one step further and added an educational component: some tasks require players to brush up on their art history knowledge.

We loved crafting every detail of Art Heist. Now, only one question remains: are you ready to accept your mission?

Design Process

Target audience

We designed our game for a target audience of adults and kids aged 13+, as some of our puzzles are challenging and/or require some knowledge of art history.

Formal elements

We incorporated many of the formal elements into our game design. Art Heist is designed to be a multiplayer cooperative game, with the players competing against the game itself. The objective, as clearly outlined in the brief onboarding sheet, is to catch the thieves – in this way, it could be formally labeled a chase game. The player is given resources in the form of clues and puzzles, which they must solve to unlock more clues and eventually track down the thieves. We intentionally designed the game to not have many rules, as we felt they would unnecessarily constrain players. However, after playtesting we added a time limit to create a sense of pressure and escalate the game’s intense tone.

Types of fun

We designed Art Heist with four main types of fun in mind: fellowship, discovery, narrative, and challenge. Our game is ideally played by 3 people working as a team to solve puzzles and advance through the narrative. By promoting teamwork and mutual satisfaction upon accomplishing goals, our game is designed to foster fellowship amongst close friends and strangers alike.

As players solve clues, they are able to access more pieces of the game – first, they must figure out a combination to open a locked box, and then must complete a puzzle to learn the url of the game’s digital portion. We purposefully used these mechanics – opening a box and typing in a mysterious website address – to allow players to experience the joys of discovery.

Narrative is an especially important part of Art Heist. Players are expected to figure out most of the mechanics by themselves, but they are explicitly told that they are spies tracking down art thieves. This narrative runs throughout the game, culminating in a choose-your-own adventure-style chase of the thieves on the website. We used this narrative to create a tone of excitement and mystery in our game.

Finally, the series of puzzles and clues in Art Heist presents a rewarding challenge. After some playtesting, we added a time limit to enhance this challenge.

Game architecture

Our game consists of many loops and arcs. For example, the crossword puzzle can be seen as a loop: players come in with a mental model of how crossword puzzles work, so they make the decision to solve it and take the action of filling it out. They then see that the circled letters are a clue to something else, serving as positive feedback. Finally, they update their model to understand that each puzzle they solve will give them a clue to the next puzzle. Although each puzzle is different, this series of mechanics is constant throughout and thus constitutes a loop.

In addition to this loop, Art Heist includes several narrative arcs, with one clear example found in the online portion. Players begin the digital component with a mental model: they know they have pieced together clues in the past by trying things out blindly until a pattern emerges. They immediately must make a decision between the two choices on the screen, and perform an action based on that decision. The rules then require another choice to be made, as shown on the screen. Eventually, the players receive positive feedback: they catch the thief! Players then draw on their prior knowledge of the word “thief” and the goal of the game to update the mental model.

Space & narrative

In Art Heist, each piece of the larger puzzle relates to the narrative of tracking down thieves. For example, we used art history trivia as clues for the crossword and cut up an art piece to make a physical puzzle. We tried to make it feel like there was an element of physical space involved in the narrative by placing some of the clues in a locked box. The digital portion of our game also places players into a designed space by describing their surroundings as they make choices and chase down the thief.

Game onboarding

We intentionally made our onboarding process as unobtrusive as possible. We have one sheet with a very short explanation of the context of the game, used mainly to help players feel as though they are entering the narrative as detectives arriving at a scene, rather than learning the mechanics. Otherwise, we rely on players learning by doing, rather than reading. Clues are not obviously initially related, and allowing the player the freedom and independence to struggle and succeed on their own cultivates a satisfying dynamic. We learned through playtesting that this was generally enough for players to feel comfortable diving into the puzzles.

Visual and auditory design choices

All materials of the game fit the aesthetic of an art museum. We laminated all paintings to create a sophisticated feel. Our game included a wooden decorative box to give players curiosity of what is in the box and to design for satisfaction when the box was finally opened through previous clues.

Game Map

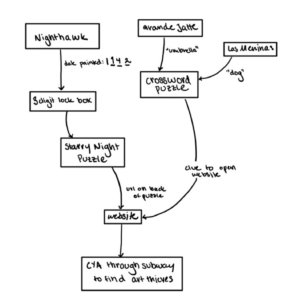

This map demonstrated the components of our game. The top layer has the three paintings we include in our game: Edward Hopper’s Nighthawk, Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, and Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas. Then the arrows include which piece you need from the previous component for the next component.

Game walkthrough

See here for a walkthrough of our game.

Playtesting and Iteration History

We had 2 primary iterations of our game: one to successfully balance the game’s difficulty for our target audience, and one to add an element of suspense and pressure.

In our first playtest, we tested the difficulty of the questions on the crossword puzzle. Originally, our crossword puzzle contained clues related to both art history as well as Stanford trivia. To make the game more accessible and interesting for non-Stanford audiences, we decided to limit the clues to art history trivia. However, during our first playtest, we realized that to successfully calibrate the difficulty to balance the game for our target audience, we had to make the art history trivia more accessible for non-art experts. The easier art history trivia made the crossword puzzle much easier to complete and created an appropriate level of challenge for our playtesters.

In our second playtest, we tested the speed of gameplay. We found that while players were able to keep a fast pace aligned with the premise of the game, to catch the thieves before they escaped. However, just as the locked box on the table adds an element of tension, one of the players suggested incorporating a timer for added pressure. We then added a 25-minute timer to our game. In our subsequent playtests, we observed that the added time pressure was a beneficial aspect of our game. The visible countdown provided an extra level of encouragement to solve the puzzles with speed. Player feedback about the time pressure was also overwhelmingly positive. Players commented that it provided incentive to go faster, and that it helped to tie the narrative arc together: the players felt like they had to catch the thieves before they escaped. The inclusion of the timer increased the fun by increasing the game’s level of challenge.

Ultimately, our final playtest was a successful combination of all of our past playtesting iterations. We found that our playtesters were generally less knowledgeable about art and relied on their phones to look up crossword clues, but the level of difficulty was appropriate and didn’t hinder gameplay. In addition, players were able to identify the crossword’s built-in hint. The built-in hint for the crossword puzzle was the circled letters, and groups noticed that they didn’t have to complete the entire puzzle; they just had to fill out enough of the crossword so that the circled letters were filled in. Overall, our playtesters’ favorite part of the game was the shredded Van Gogh puzzle. Players commented they enjoyed putting it together and it was the moment things ‘clicked’ for them.

Our game successfully fostered fellowship, discovery, narrative, and challenge. In each playtest, we observed teams work together to solve clues. Each playtester offered their own strengths when solving each puzzle, creating a fun dynamic of collaboration and fellowship. The narrative about players being members of the same detective group also helped to set the scene for fellowship. As the players moved through each piece of the puzzle, they experienced the joy of discovery as each clue led to another, and we saw several “a-ha” moments where playtesters realized what clues were relevant to the next task. Players also experienced narrative fun, and extra elements of the locked box on the desk and the hands-on nature of each puzzle added to the overall story arc and narrative experience. Each puzzle was also appropriately difficult to allow players experience the fun of challenge and puzzle-solving.

In the future, there are several potential ways to improve our game. First, it might be helpful to provide a frame where players place the completed Van Gogh puzzle — it is more aesthetically pleasing than tape, and guarantees that the players will notice the URL written on the back. Second, since some players found the final “Choose Your Own Adventure” to be rather easy and anticlimactic, a future iteration of Art Heist could include a digital puzzle of some sort with a bigger celebratory finale. Overall, our playtesters enjoyed the concept of the Art Heist, and the game could be turned into an escape room that utilizes a physical space on campus, like the Cantor Center. This would ground the game in a particular space, which allows players to better visualize themselves within the narrative. In the future, we could also improve the accessibility of our game. Art Heist relies on many visual elements which are not accessible to those who are visually impaired. Additionally, our game relies on a degree of education or knowledge about the art space, which is not particularly accessible. We could modify our game to better suit the interests of certain audiences: for example, for an audience with lots of music knowledge, the trivia could be music-related; for a visually impaired audience, the clues could be auditory.

Final Playtest Video

See here for our final playtest video.

Final Playtest Feedback

Blake

For the final playtest, I moderated our game, Art Heist. We played two sessions. Both sessions went smoothly, and the players were able to solve all the puzzles in a reasonable amount of time. There was one member in the first group who knew a lot of the trivia, and she was able to solve the crossword puzzle extremely quickly. The other interesting thing we observed was that the players didn’t finish the crossword puzzle once they had found the letters in the circled squares. So they were able to find a shortcut based on the insight that the circled letters would be important. Additionally, we decided to add a timer for our second playtest based on the observations from the first playtest. The first group took around twenty minutes so we put a twenty five minute timer for the second group to see how it would affect the game. The timer was well received by the players, and they noted that it affected how quickly they moved through both puzzles.

Will

During the final playtest, I took notes of other players participating in our games. We had two playtests – players seemed to enjoy the game, and feedback was positive. A game that I was able to playtest the game MoonJumper. The game was created in Unity, and the gameplay was essentially an ingrained tutorial that progressively revealed game mechanics to the player as they traversed a map. The player begins with the ability to move using a joystick, and progressively more challenging obstacles teach the player the distinct mechanics of jumping, double-jumping, wall-jumping, and a grappling hook. I thought that the design was done well – while the gameplay was essentially a tutorial, the progressively more challenging checkpoints along with intuitive teaching of mechanics (never explicitly stated, but obvious through map design) cultivated a satisfying experience. One moment that was especially rewarding was finally figuring out the wall jump mechanic and traversing a seemingly impossible canyon. I was also impressed by the visuals. The game was played in the third person, and the simplicity and elegance of the player and map was visually pleasing.

Allie

The first game I playtested was Closed Door Office Hours. It was narratively very interesting: we were told that we were students locked in our professor’s office and had to solve clues in order to get out. As the game progressed, it was revealed that the professor had locked us in the office in order to clear his name in the investigation of his daughter’s murder. I really enjoyed how pieces of the narrative were revealed throughout the game – it created a deeper sense of satisfaction and discovery than simply accomplishing the goal of escaping. Closed Door Office Hours was designed as a physical escape room in a space inaccessible to us during class, so we were only able to playtest two of the puzzles. Both were enjoyable, though not very challenging – however, the other puzzles in the actual room might be more difficult. One piece of feedback I had was to include an age limit, as there is some mature content in the game. Also, I would add subtitles to the video to make it more accessible to people of different hearing abilities. Overall, though, I really enjoyed Closed Door Office Hours!

I also playtested Monster Mayhem (the game I was assigned, Dicepto, did not need more playtesters). I was very impressed with this game – it was all digital, and the animation was extremely well done. The music created a playful and light tone, which complemented the game mechanics well. It was challenging enough to be interesting, but not too difficult that it became frustrating. It is a 2 player game requiring both teammates to navigate the world perfectly in sync, which fostered fellowship between me and my partner. The narrative was also interesting: the two characters have to stick together around people to disguise themselves. One piece of feedback I have for the creators is that this storyline could be made more clear – they had to explain the narrative to us as there was no onboarding at the start of the game. Also, the game ends when you reach a certain patch of green, but there is nothing signifying the end goal of the game, which could be added in future iterations. Overall, it was an extremely enjoyable game!

Alex

During the final playtest session, I playtested 2 games: Monster Mayhem and Dorm Break. Monster Mayhem is a 2-player game created in Unity requiring 2 players to control separate characters but work together to successfully reach the finish line. I really enjoyed the game. The game had a great atmosphere thanks to the choice of music, and the game itself was well-designed and aesthetically pleasing. I enjoyed the fun of fellowship and challenge. I had to successfully navigate the game with my partner, with one player using the arrow keys and the other using the WASD keys, which required coordination, collaboration, and communication. This allowed me to experience fellowship with my partner. I also enjoyed the fun of challenge, since the game itself required a certain level of skill that gradually increased as I progressed through the learning curve of the game. The level of difficulty was perfect: the game was challenging, but not frustrating. In the future, I would have loved to understand more of the game’s narrative. Where are the “monsters” (given the name of the game)? Why do the two characters have to stay together in order to survive around people? I also playtested Dorm Break, which was an escape room set in a dorm room. The game was highly realistic with several familiar objects and activities to college students, like a to-do list, a diary, Trader Joes’ Cinnamon Schoolbook Cookies, and a map of campus. Each individual puzzle was challenging but fun to solve, and I enjoyed the “a-ha” moment at the end where each puzzle corresponded to a clue to unlock the locked iPhone. I enjoyed the embedded narrative within the game, since as each clue was solved, more and more of the story/mystery was revealed to the player.