For this critical play, I played What Remains of Edith Finch, a first-person exploration video game released in 2017. Due to its mature and dark themes, I assume the game is targeted toward an older audience. There are four main aspects of this game that fit the feminist theories described in Shira Chess’ Play Like a Feminist: the emotion present in the narrative, the characters used, the empathy-driven gameplay, and the freeform structure of the story. Interestingly enough, the freeform structure of the story is my only critique of the game.

Emotion-Based Narrative

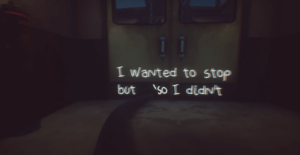

According to Chess, a feminist game must contain a feminist story, and a feminist story is one rooted in emotion. The stories told in What Remains of Edith Finch are so emotion-drenched that they are impossible to understand from any other perspective. They serve as retellings of real events, with the emotion guiding the exaggerations that create the fantasy elements. For example, when the player reads Molly’s death, they know that (logically) she didn’t actually turn into an owl, a shark, or a monster. However, the story is told this way to drive home how Molly felt being locked away from her family as her primal functions took over. These feelings are evident in Molly’s narration of the story, particularly when she says “I wanted to stop but also I didn’t”. Molly’s description of herself as a monster notifies the player of the internal struggle that her final diary entry is centered around.

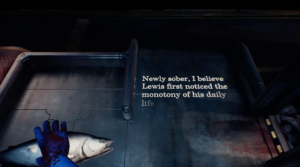

Nearly all of the other stories use fantasy in this way: the daydream of being a king to reflect Lewis’ depression or the tale of Barbara and the serial killer to reflect a fear of being forgotten or past one’s prime. The narrative forgoes literal retelling in favor of an emotion-first interpretation of events. This evokes somewhat of a discovery type of fun (perhaps a more feminist version of it) that’s intertwined with the narrative type of fun, as players come back to the game to explore more the family’s stories (or, more literally, more of the house).

Characters and Feminist Perspective

Chess also emphasizes the need for feminist games to “speak a kind of truth that resonates with diverse and underrepresented audiences” (Chess 59). What Remains of Edith Finch does this both directly and indirectly. For starters, the playable protagonist (along with several of the other main characters) is a woman. Edie finch—who is dead while Edith explores the house but is frequently mentioned and is present throughout the setting—serves as the matriarch of the Finch family.

Aside from the obvious female characters, the game displays feminist perspective through the range of character emotions and experiences. Characters deal with mental illness and grief. One character commits suicide. Edith is assumed to have died during childbirth. Though all tied together by death, characters reflect the struggles of audiences that are often underrepresented in more traditional games.

Gameplay and Empathy

Empathy, another feature of feminist narrative, is a direct result of the gameplay style in What Remains of Edith Finch. The player explores the different rooms of the Finch house, where each family member has a memorial that contains a written diary entry on their death. As Edith (whom the player plays as) reads each entry, her voice transforms into the voice of the late family member (or someone that knew them well, like in Lewis’ case). The player hears the story from that perspective, and is removed from the house setting to enter the fantasy world in which the entry takes place. This, in combination with the emotion-heavy narrative style of the game, forces empathy because the player must see things from the perspectives of these characters.

The player even morphs into this character during these scenes. For example, although Lewis’ story is not told directly from his perspective, when the player’s character looks down at their hand, they see the blood-stained gloves of Lewis.

Freeform Narrative and Lack of a Climax

Finally, Shira describes a feminist narrative as “not being climax-centric” (Chess 60). After the first hour (of two) of playing the game, I thought I had a pretty good idea of how things would go: after getting the stories of all of the family members, Edith would courageously “break the curse” by not focusing on its existence (or lack thereof), and we would get some closure about the family moving forward. Literally none of that happened. The end is purposely ambiguous–players never get confirmation of the curse of the end of the family. Certain things can be inferred (Edith’s death, for example), but there is no large climax or neat ending. Everything just fizzles out and is left for the reader to ponder on.

This is my only critique of the game. The ending left me deeply unsatisfied. I was awaiting a twist or lesson to close everything off, but there was none. Chess labels this conventional method of storytelling as a “heterosexual masculine perspective” (Chess 59). Freeform, never-ending stories are feminist. But, I can’t help but feel like for this story in particular (one that so closely borders the line between realism and fantasy), some type of insight into what I had spent the past couple hours experiencing would have been nice. That being said, as someone that’s a huge fan of magical realism in stories, I wonder if the reason I disliked the ending was because I didn’t expect it. Maybe I’m so used to the “heterosexual masculine perspective” in games that an open-ended game feels wrong.

Regardless, I enjoyed this game. I find that the more time passes and the more I get to think about what I experienced, the more I like it. I feel that exploration-based, narrative-heavy, female-led games are becoming more common (Life is Strange, Gylt, Night In the Woods), and that makes me happy because as someone who never classified themselves as a “gamer”, it allows me to engage with a new form of storytelling with stories and characters that I can finally relate to. For the first time in a long time, I’d like to start making games, too.