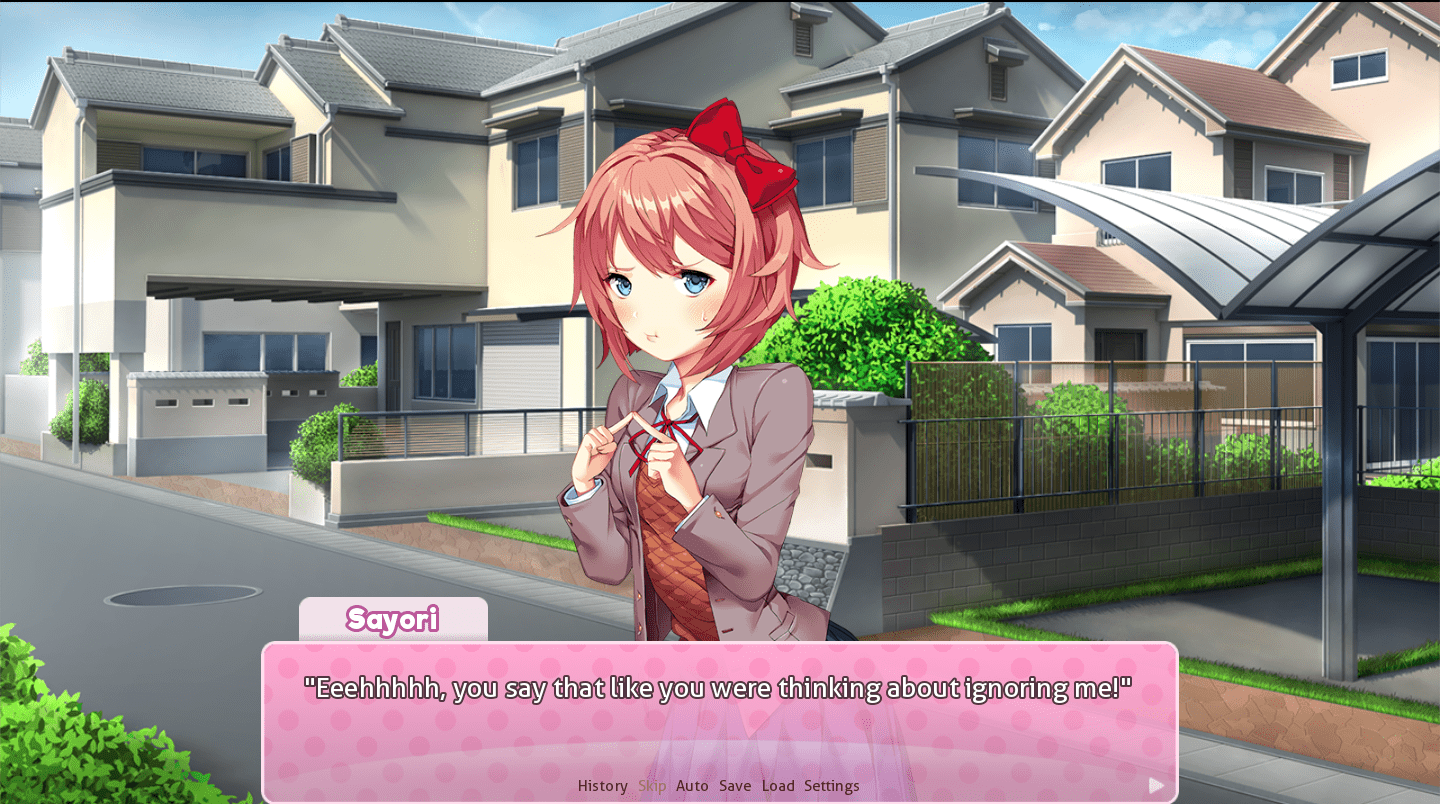

The game I played was Doki Doki Literature Club by Team Salvato for PC and later console. It is a visual novel/dating sim for one player, where the primary method of interaction for the player is to click and read the next line of text in the textbox, as seen below.

However, as the player joins the “literature club”, they are given “assignments” to write poems. The player then picks words to include in their poem. The girls in the club will react to the poem positively or negatively depending on the kinds of words the player chooses, creating a dynamic where the player tries to pick words that align with their favorite character (Sayori, Yuri, or Natsuki) in order to unlock special graphics and cutscenes. This, along with the lighthearted music creates the dating sim aesthetic. As if to emphasize this perspective, the game starts by introducing Natsuki, Yuri, and Monika as “Girl 1”, “Girl 2”, and “Girl 3”, followed by Natsuki complaining about Sayori “bringing a boy” to the club which, playing as feminist, poses a concerning terminology/example of objectification of women and heteronormative assumption of the player’s gender.

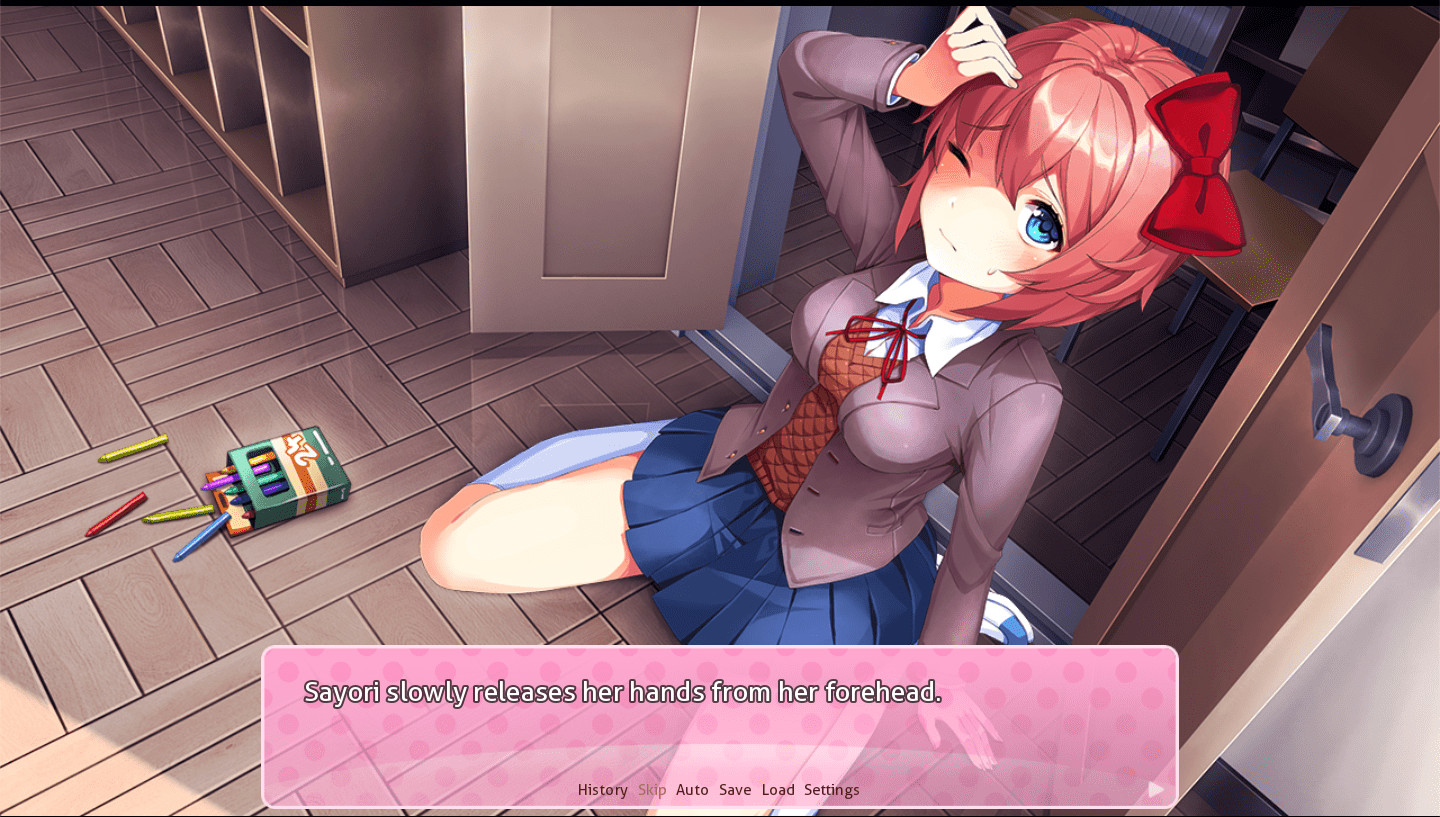

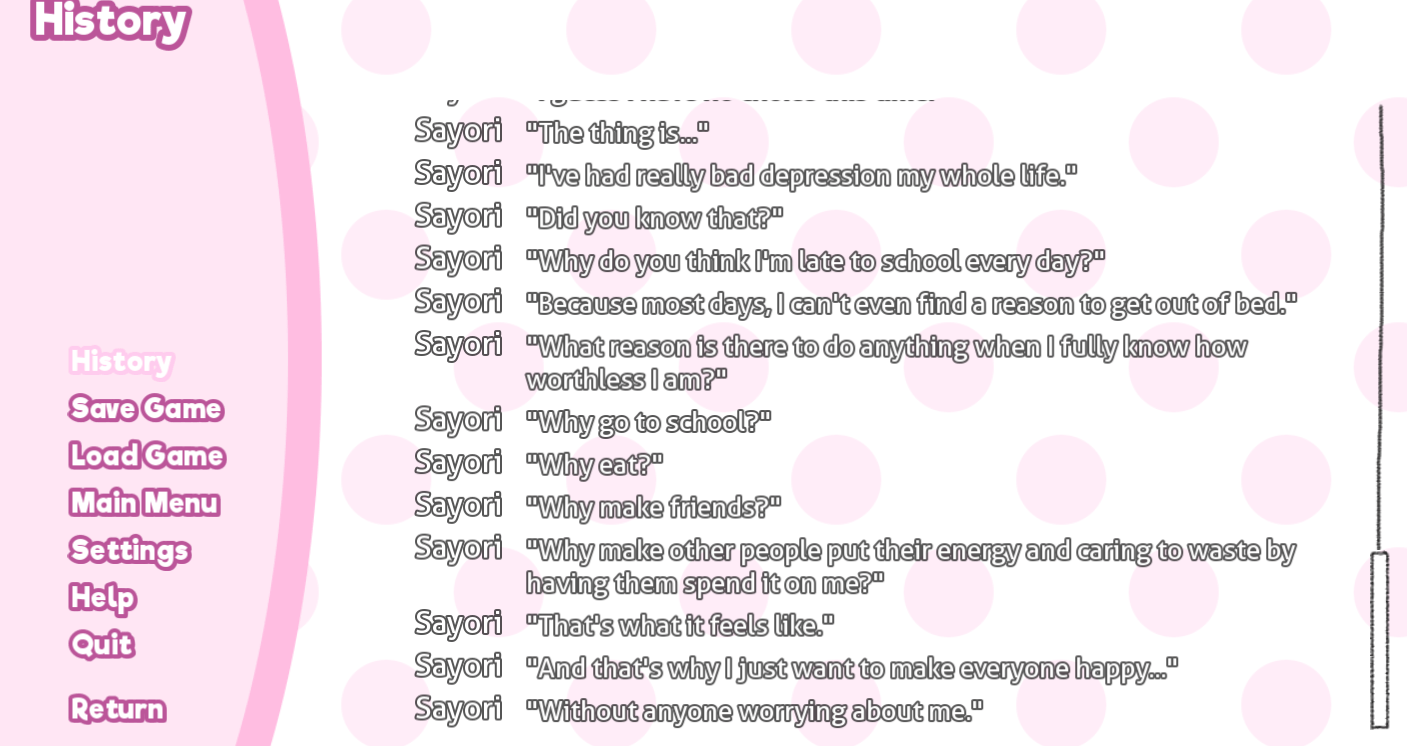

However, this potentially familiar aesthetic and a “daily routine” of writing poems lulls the frequent dating sim player into a false sense of security. As each day passes, the club begins to prepare for the cultural festival–a dating sim staple–, Monika grows increasingly absent, and Sayori confesses that she suffers from depression.

Following this raw reveal, the game begins to unravel, turning to much darker and serious topics including mental health, suicide, death, and autonomy though the game’s meta, including deleting saves, loads, glitchy graphics, errors, forced quits/ restarts, files, special “unlockable” poems, and even deleting itself at the very end.

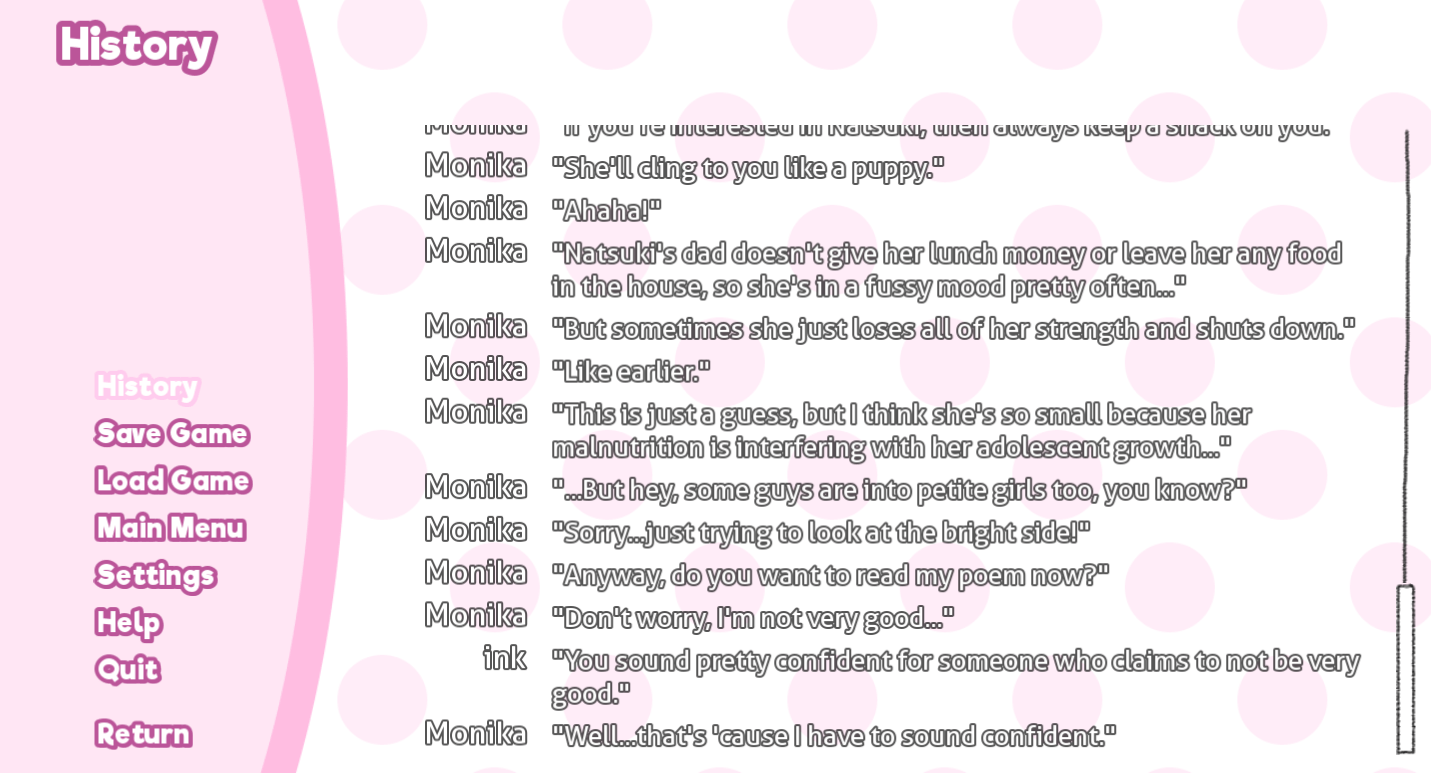

Eventually, it is revealed that Monika, has gained self awareness/consciousness of her reality as a game character. Despite being a “non-datable character,” she obsessed over romancing/claiming the player, who she believes to be the only person in their world with autonomy. From a feminist perspective, Monika is perhaps the most “agented” female character, as she has learned to code in order to cause glitches, remove characters in later playthroughs, and follow through with her obsession.

Altogether, DDLC puts tropes of the dating sim genre in question–tropes that it itself follows in the first part. It gives the player choices, but questions its own script. It even gives the “datable” characters agency to do things beyond simply trying to date the main character. As a psychological horror, these actions often involved death and mental illness (Sayori is suicidal, Natuski is malnourished/abused, and Yuri is obsessive and self-harms). Sometimes I felt like these character traits were more meant for shock value and aesthetic, but they are incorporated well through evoking the player’s fear and concern through glitches, animations, and ultimately having the player enact their own solution to Monika’s terror by delete her character file.

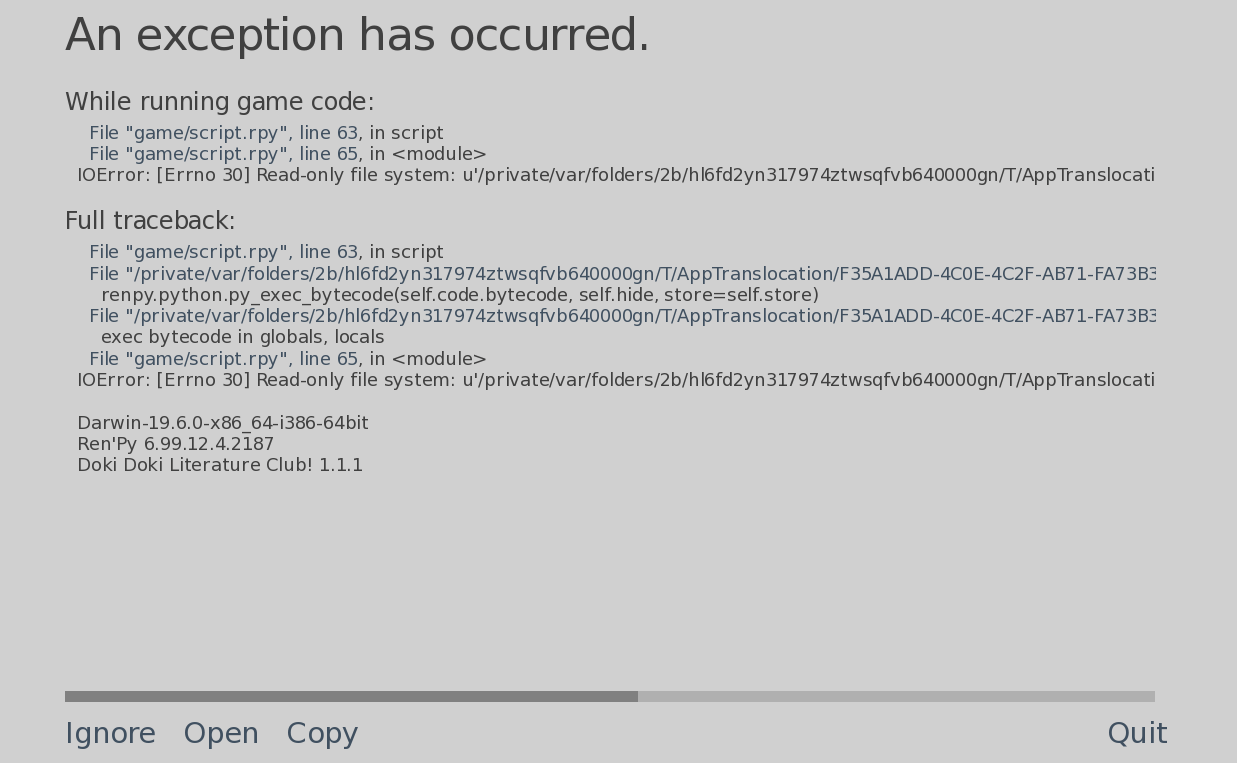

Finally, I did have some small hiccups while playing. For example, using errors as an aesthetic caused some parts to be confusing, such as the errors I got for having the application in a read-only location (which were actual errors that prevented me from reading the special poems and reaching an ending). Despite this, the unique perspective DDLC offers on the dating sim genre, as well as the agency –or, at least questioned non-agency–of its female characters make it a fascinating game to play as a feminist.