Created by Rhett Owen, Krishnan Nair, Tonya Murray, Ghisly Garcia, Jacob LeBlanc, and Trey Holterman

ARTIST’S STATEMENT

Inspired by the show Avatar: The Last Airbender, our team created The Banishment of Zuko, an interactive fan fiction narrative based on the redemption arc of Prince Zuko, heir of the Fire Nation. In this game, players take on the role of Zuko in the moments leading up to and following the Agni Kai battle with his father, Fire Lord Ozai. Players can expect to experience nostalgia and tension as they navigate through the world that they know and love from Avatar while making it change to their playstyle with the choices they make along the way.

PLAY THE GAME

To play The Banishment of Zuko, click here and use the password: zuko.

We strongly recommend opening the game to full screen for maximum enjoyment.

TARGET AUDIENCE

This all ages game is designed for consumers of Avatar fan fiction and more casual fans who have also enjoyed the show. We wish to keep the barrier of entry as low as possible, designing the game for both amateurs and frequent gamers. We do this by producing fun through exploring different narrative paths, rather than relying on puzzles and twitch-skills.

DESIGN JOURNEY

Our design team is a diverse group of 4 computer scientists and 2 learning experience designers. We started our journey by defining two concepts we wanted to incorporate into our game: the emotions that arise when making difficult choices and the harsh realities of our society (e.g., genocide). In order to make these topics approachable, we decided to center the story in the Avatar universe, enabling the player to experience the journey of Zuko, a prince in a nation that is committing mass genocide.

In the original story, Zuko has a long redemption arc where he turns away from his upbringing and becomes an ally of the Avatar. Our intention was to allow the player to choose whether to experience this arc (remaining true to the story) or to see what would happen if Zuko remained loyal to the fire nation and fixated on capturing the Avatar.

In our initial concept doc, we decided the game would primarily be played in a 2-D pixelated universe similar to Pokemon. The game play would center around the player making choices, interacting with characters, and engaging in dialogue. The sense of fun in this initial concept would come from exploration and discovery of the 2D pixel version of the Avatar universe and its people.

We created a walking simulator prototype where players could simulate Zuko’s experience and perspective (to play the game, use the arrow keys to move and ‘z’ to interact). Watch a 1 minute preview video below.

https://youtu.be/xks8LFR4lWI

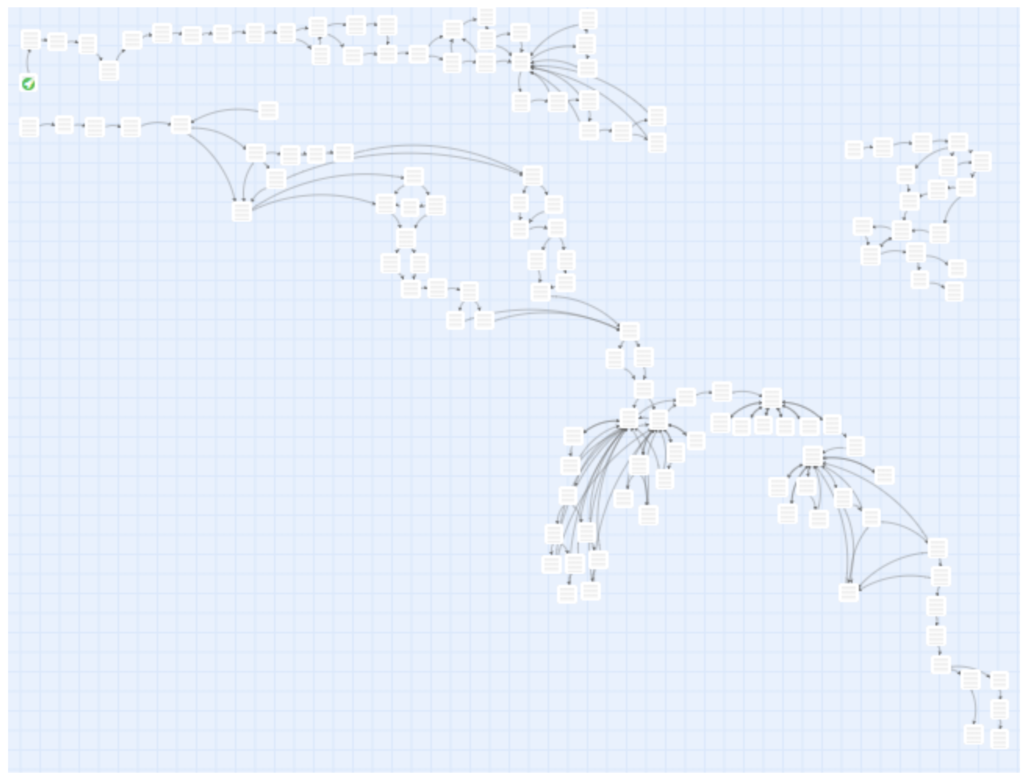

At a point when the feasibility of the Unity game was in doubt, we created a Twine narrative as an experiment to help us form a structured story. We suddenly found ourselves with two very different but equally viable options for our game.

After much deliberation and multiple rounds of playtesting, we ultimately decided that the Unity format would limit our ability to introduce and reinforce “choice” as a primarily game mechanic. We saw that it could be a fun game that focused on the spatial aspects of visiting the four nations, but it was not well aligned with the story we wanted to tell and the emotions we wanted to generate. The pixel artwork and size of the speech bubbles also blunted the emotional impact we felt we could deliver from the game.

This was a pivotal moment in our design journey, as it led to a deeper focus on the story rather than exploration of the environment. Our game ultimately became an interactive fan fiction narrative built on Twine. We decided to pursue a vertical slice rather than an MVP in order to aim for depth in the story instead of breadth in the settings.

Ultimately, we enjoyed experimenting with both platforms and learned a lot in the process. We are happy with the decisions we made, as well as our ability to quickly pivot and refine our direction through playtesting and constructive deliberation among our six team members.

FORMAL ELEMENTS

The Banishment of Zuko is a single player interactive fan fiction narrative built on Twine. The objective of the game is to walk through Zuko’s narrative arc while making choices about whether to turn away from his upbringing or to remain true to Fire Nation ideals. The story is told through narration, dialog, Zuko’s thoughts, and the choices presented to the player. The majority of story nodes contain art from the actual show and one to three links to advance the story to the next node. Most screens have a choice between a kind action and an unkind action for Zuko to take. A small set of resources are collectible and are intended to influence later events in the story. They include a blue spirit mask, broadswords, Iroh’s dagger, a family portrait, and a letter from Zuko’s mother. An important boundary for the game is that the places, events, characters, and dialog of the story must be situated within and remain true to the Avatar franchise. Minor deviations such as introducing the Cabbage Vendor before he appears in the canon story are included in service of fan enjoyment. The outcomes of the player’s early choices are designed to win Lord Ozai’s approval or face his wrath. The player may choose to follow the canon story, which leads to a battle with Lord Ozai followed by banishment, or experience an alternate story, where Zuko’s burns are merely a training accident and he is banished for defending himself so poorly.

MOODBOARD & AESTHETICS

In terms of aesthetic objectives, we wanted to create an emotional journey for our players. The primary emotion we designed for was nostalgia. This game is designed for fans to relive the experience of the beloved story, including allusions to key characters like Uncle Iroh and Azula, and walk-on appearances of fan favorites like the Cabbage Vendor. We designed the introduction of the game to include the opening credits of the show, which we confirmed in our playtesting creates a strong and instant connection to our players’ existing mental models.

Additionally, we wanted players to experience the tension in decision making between choosing to behave kindly or unkindly. Throughout the game players are encouraged to decide, will they stand up for the abolishment of genocide or succumb to familial pressure and continue to play a complicit role in oppressive systems. Through various choices, big and small, players are positioned to take an active role in the unfolding of the narrative. We anticipate that players might follow one path on the first play through, then play the game again and choose the opposite path.

In our game, we attempt to make the text appear as if a fire is being lit behind it. This design choice was inspired by Zuko’s character, as he constantly feels left in the dark and is slowly uncovering the truth. We believe the darker aesthetic will also set a somber mood for players as they embark on the journey.

SENSE OF SPACE

Sense of space was an important component of our process and thinking. We first considered making a MVP game where Zuko would visit each of the four nations, making one or two consequential choices in each. The choices would lead up to the final showdown with the Avatar. After much discussion, the team concluded that this would be too predictable as the main story points in each nation are well known by the fans. The world tour would not meet the goal of developing the emotional impact of the choices.

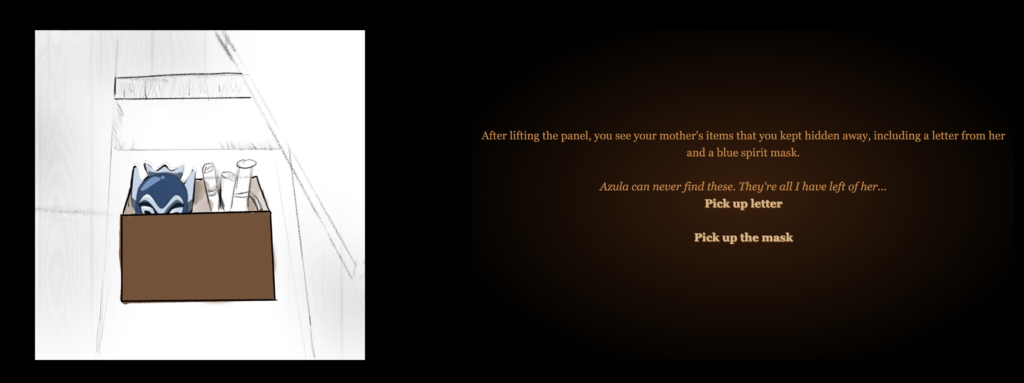

Instead, we situated the game as a slice that takes place entirely within the Fire Nation. In order to give the game a sense of space, we engineered the story so that the player must visit several places within the Fire Nation: Zuko’s bedroom, the war room, the palace grounds, and the stadium. To create a sense of space, we used imagery, sound effects, and text to situate the player in each of these locations. For example, when Zuko is packing his belongings, he can move a wooden floor panel to reveal his mother’s belongings. This scene is accompanied by the creaking sound of the drawer to put users, regardless of visual ability, into the scene. By interacting with the narrative, players are encouraged to navigate through different locations of their choosing.

TYPES OF FUN

Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc, and Robert Zubek write about the MDA (mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics) as a formal approach to understanding games. In their 2004 paper entitled, “MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research,” they outline 8 different types of fun that contribute to a game’s aesthetic. They are: Sensation (game as sense-pleasure), Fantasy (game as make-believe), Narrative (game as drama), Challenge (game as obstacle course), Fellowship (game as social framework), Discovery (game as uncharted territory), Expression (game as self-discovery), and Submission (game as pastime). The fun of our game comes from the combination of two elements: Fantasy (game as make-believe) and Narrative (game as drama).

Fantasy (game as make-believe) comes from taking Zuko’s perspective as the protagonist in this story. The original Avatar story is largely centered around Aang, the Avatar. Our playtesters were delighted to make-believe that they were Zuko (instead of Aang) and appreciated the opportunity to center his experience in the unfolding of the story. It was a perspective that they had not previously considered, especially since we decided to fill some parts of the story that were not covered in the original story. For example, we never see Zuko pack before his banishment in the series, but in the game we create an opportunity for players to experience the emotional journey that packing may have been for him.

Narrative (game as drama) is also a key element in our game. There are layers of drama that the player must experience and respond to as they traverse the game. We decided to create and heighten drama by centering “choice” as the primary mechanic. Choice is what moves the narrative forward, rather than Submission (idly consuming the narrative). The narrative is an active experience co-created by the game system and the player. The player must make a series of choices, both big and small, to expose and resolve the drama. For example, the story starts with Zuko waking up and deciding what to do and where to go. Ultimately, Zuko must decide where he will stand up or stand down to his father who is planning to murder innocent people. To further heighten the sense of drama, the game does not allow players to “go back” and adapt their choices. They must live with the consequences of their actions. In this way, choices become “expensive” which creates tension for players in the game. Lastly, the game’s sound design helps amplify the drama by imitating an accelerated heart beat during key scenes. This helps create an emotional response and also creates a subtle urgency to move forward and resolve the drama.

Lastly, fun is enhanced by the nostalgia of encountering familiar art, characters, and story points. In playtesting, all players mentioned feeling a pleasant sense of nostalgia while moving through the game. They shared that nostalgia was the primary emotion conveyed by the game which aligned with our goals and intentions. They enjoyed reliving the story and appreciated the twist of seeing the world through Zuko’s point of view. Playtesters also enjoyed cameo appearances by beloved characters such as the Cabbage Vendor, Uncle Iroh, and Zuko’s sister Azula. In terms of familiar art, playtesters responded well to the opening credits which reminded them of the series. They also appreciated revisiting story points and symbolism, such as seeing the Blue Mask which evokes a sense of foreshadowing. It serves as a reminder of Zuko’s good nature and signals a possibility of what the future may hold in store for him.

GAMEPLAY & MECHANICS

The main mechanic employed by our game is choice. By clicking html links to choose Zuko’s path through the story, the player takes an active role in the unfolding of the story.

We considered and decided against adding puzzles to the game after playtesting a puzzle in the Water Nation. The puzzle involved finding the exact path of responses needed to exit a story loop and meet the Avatar, with clues given by some of the other characters. Playtesters greatly disliked this experience, they wanted the narrative to continue to move smoothly forward without frustration. We asked playtesters about adding other kinds of puzzles, and were told they felt it would detract from the experience. Instead of puzzles, we focused on crafting story lines that gave the player a feeling of agency but ultimately returned to the main flow of the story.

We considered adding a hidden “points” system to track the number of kind and unkind choices the player made to determine the final outcome of the game. This design seemed likely to lock a player into a particular role and to force us to maintain a lot of branches. We opted instead to have the consequences of the choice happen immediately so that the player could feel the impact. We worked to balance the choices so that both results were satisfying while still ultimately leading back to the main narrative path.

CHOICE AS PRIMARY MECHANIC

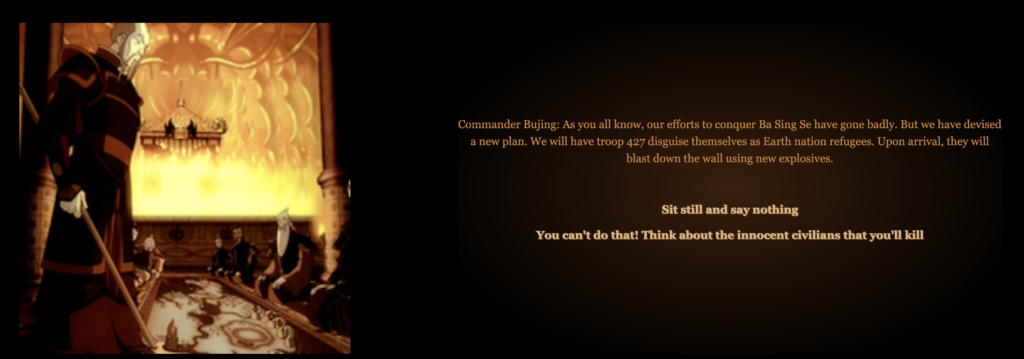

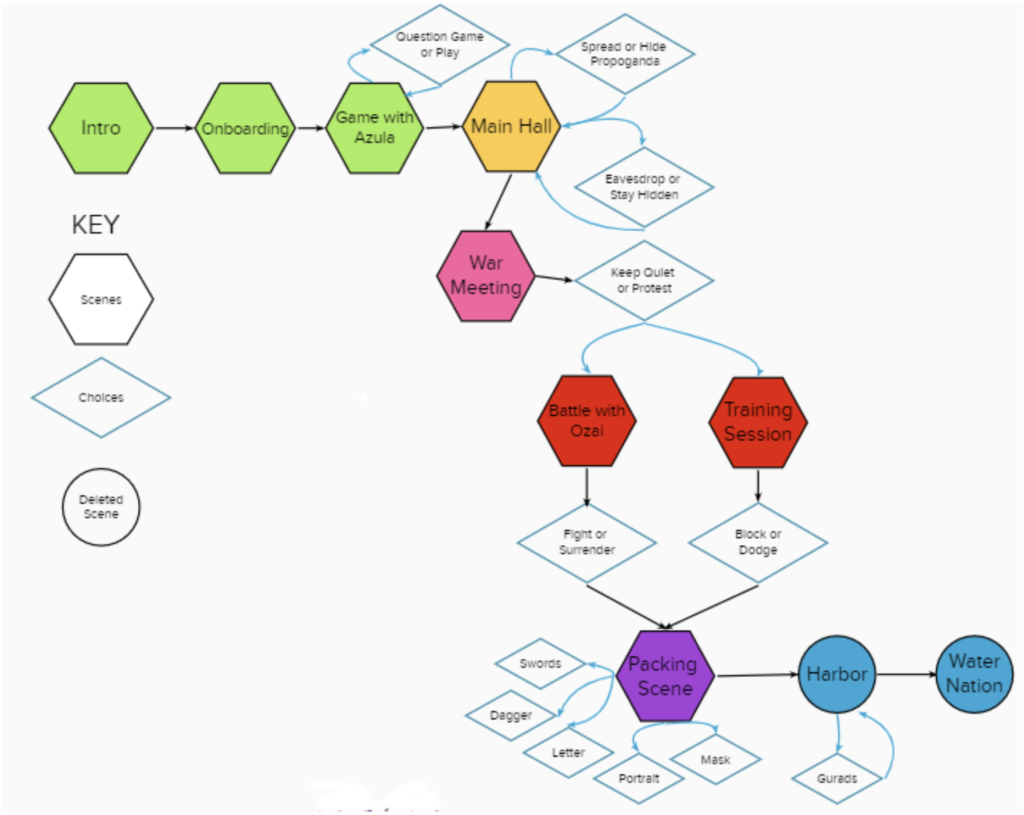

Our game features one major choice that significantly alters the storyline. During the war meeting, the player must choose whether to keep quiet or protest against genocide in a war meeting. This leads to either a training session or a battle with his father. Secondary and tertiary choices guide the player towards this pivotal scene.

SECONDARY CHOICES

A series of secondary choices are designed to set up future story points:

- Attack or forgive the Cabbage Vendor. If Zuko forgives, the player can later give a cabbage to a general to get out of trouble.

- Hide or spread propaganda posters. This later affects whether Zuko is rewarded or punished by his father in the meeting scene.

- Whether or not to eavesdrop. This sets up a later choice of whether or not to reveal the information to his father.

- Which 3 out of 5 possible items to pack. This sets the player up for future events in the Earth and Air nations:

- Broadsword. Without the broadswords, Zuko would be forced to live as a person that didn’t have any form of defense and would explore the Earth Kingdom from a non-aggressive standpoint.

- Blue Mask. If Zuko doesn’t pack the blue mask, he won’t be able to pose as the Blue Spirit to rescue Aang. The player would have to consider the choice of whether or not to help Aang without the benefit of anonymity.

- Letter from Zuko’s mother. If Zuko packs the letter from his mother, it would open plot lines where he seeks the truth about his mother’s disappearance.

- Family Portrait. The family portrait is a symbol of Zuko’s desire to be at his father’s side again. It also serves as a constant reminder of his mother, and would be used to remind the player of these conflicting impulses later in the story.

- Iroh’s Dagger. Keeping the dagger would lead to scenes that encourage the player to contemplate the role his uncle plays in his destiny and his understanding of good or bad.

TERTIARY CHOICES

To help give the player a sense of agency and advance, but not alter, the storyline, the game also features tertiary choices. For example:

- Whether or not to play Azula’s game

- To leave the war meeting quietly or argue with his father

- To listen to or argue with Iroh’s advice to surrender

- To fight back against his father or surrender (Zuko gets burned either way)

- To block or dodge during the Training Session with his father

STORY MAP

We created two story maps to illustrate the main scenes and choices.

PLAYTEST OVERVIEW

Playtesting was a major driver of how we developed our game, not just in terms of what mechanics and elements we chose to represent our game with, but also the medium we chose for our game. As mentioned previously, our earliest prototype envisioned a 2 dimensional pokemon-like pixelated world where the user would have free reign of moving Zuko and engaging with other characters. There were some early signs of trouble with bringing this vision to life, so as a backup, we began playtesting with two versions of our game: a Twine narrative game and the Unity pixelated world. We brought both versions, first to friends and family and then to in class playtesting to see which game users resonated with the most.

As a single player game and with multiple people on our team available to moderate, we were able to get a large number of playtesters from our class early on. We also leveraged friends, family, roommates, and partners of all ages to play test our game. The game has been tested by 15+ target users. While we had many iterations and playtests over the past few weeks, we have chosen to highlight three major iterations.

ITERATION 1: PIXEL VERSION

This version consisted of a pixel Zuko walking alone on a plane, and a Google spreadsheet with Avatar artwork and some example story text. We tested this concept with 4 classmates who were Avatar fans and had played Pokemon as children.

What went well

- Playtesters appreciated the idea of playing from Zuko’s perspective. They also liked Zuko’s redemption arc, which helped validate that as a good direction forward.

- They liked that we are trying to stay true to the original characters.

- They liked the Pokemon style because of the combined nostalgia of Avatar and Pokemon.

What didn’t work

- The choices we asked players to make (e.g. talk to or ignore characters, kick or fire punch this father) did not feel consequential

Changes we made

- We focused on efforts on building a narrative in which the choices felt difficult, emotional, and consequential.

ITERATION 2: PIXEL VERSION VS. NARRATIVE VERSION

The second major milestone was to playtest both versions of our game and commit to a development platform. This was the most challenging part of our design journey! We had 4 more playtesters, as well as feedback from Christina and Kally to help guide this decision. In this version, pixel Zuko could walk past Iroh and guards to another room to see Ozai. In the Twine version, Zuko was quickly banished from the Fire Nation and had several interactions in the Water Nation (available in the final game as Deleted Scenes)

What went well

- Both versions worked well, overall, and had different strengths and limitations.

- Playtesters had all sorts of fun walking around, exploring the world we built in Unity.

- They also quickly understood the narrative we were taking and enjoyed feeling like Zuko in the Twine version. The introduction felt delightfully nostalgic to Avatar fans.

- We observed lots of smiles and laughter in both the Unity and Twine versions of the game.

What didn’t work

- Choices! Players felt many of the choices were trivial.

- Loops in the Water Nation that involved a puzzle to find the exact path to finding the Avatar were greatly disliked by playtesters. They wanted a smooth experience where it wasn’t difficult to keep moving the story forward.

- Players told us they were more interested in following the story than in solving puzzles or challenges.

- Players reacted negatively to dialog they felt was out of character, such as Zuko saying, “Yikes.”

- The original story felt too linear. Players wanted more agency, and a satisfying resolution at the end of the playtest.

Changes we made

- Since we were keen on building a game centered around choice, specifically tough choices, this playtest (alongside a lot of group discussion) helped us lean into the narrative game on Twine.

ITERATION 3: NARRATIVE VERSION

The last major playtesting milestone was deep diving into the narrative game to refine the story and game mechanics. We tested this version with 6 additional play testers and focused on how we could make our Twine game as compelling as possible.

What went well

- Playtesters enjoyed going deeper into the story and were delighted to meet more characters (e.g., cabbage man). They shared, “Of course, we’re going to destroy his cart!”

What didn’t work

- We received a lot of feedback about how we should phrase or weigh different choices to make them equally tempting.

- We also asked people what motivated them to pick certain decisions, and by and large people felt like the ‘right’ choice felt a little too obvious.

- One complaint was that when taking risks in the storyline often users ended up in twine loops. This helped us realize that we needed to reward different choices in different ways, so that a user might have an engaging experience no matter which path they take. All paths should lead to enjoyable experiences.

- The choice of the original Avatar font proved to be too hard to read, especially when it was colored red.

Changes we made

- We improved our choice mechanics after observing that it wasn’t the end story or loops that kept people from making certain selections, but the specific wording around some choices. Also, some choices felt obviously “good” or “bad.”

- For example, eavesdropping is typically seen as ‘bad’ behavior, but we were able to frame it as neutral by making sure that the options don’t feel particularly positive or negative. We started with “It’s none of my business” which seems like an obvious “good” choice. We changed the choices to “stay hidden and listen” or “get away.” These choices are not obviously “good” or “bad.” This dilemma and obfuscated clarity became a valuable element to the game as it helped nudge players to think critically before making decisions.

- We learned to use small chunks of text to not overwhelm the user. One player noted that “Clicking is more fun than reading.”

- We learned the importance of using a readable font and keeping our text colors consistent, as many players associate the different colors with different contexts.

We were able to resolve these points by carefully considering and reconsidering design decisions along the way.

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

ONBOARDING

Switching from a 2D pixel-based game to a twine-based text adventure made onboarding design much simpler. For us, the key was to throw the user right into the action. In order to get them accustomed to the idea of decision-making, we introduced them to simple decisions early on and later introduced them to more impactful choices.

PUZZLES

We wanted to focus on narrative and decision-making, and found puzzles to be largely incompatible with our game, as they detract from the experience of living out Zuko’s story. However, the game as a whole is a puzzle for players who wish to play the game multiple times. By providing choices that have direct and future consequences, players are encouraged to play through the game in order to see how specific sequences of actions can change their outcomes.

ACCESSIBILITY

Another advantage of Twine over Unity is that the game is much more accessible without having to go to extreme measures. Since the game is text-based, gameplay shouldn’t be affected for hearing impaired players, and for visually impaired players, text-to-speech web browsing options should make the game enjoyable. If this were to be a full-scale game, one of the biggest accessibility additions would be captions for every image and animation included in the game. We also did our best to incorporate all the basic game accessibility guidelines for visual impairments. For example, we improved our contrast ratios and made sure that no essential information is conveyed by a color alone.

BALANCE

Our game is not a strategy game, so we didn’t have to configure balances between different choices in a strategic context. However, we did have to consider balance between the different narrative paths that the player is allowed to follow. The game revolves around making choices, so making sure that there are equal incentives for both directions is essential to enjoyable gameplay.

WALKING SIMULATION

Our critical plays of walking simulator games informed the way we move the player through Zuko’s story. Instead of an unmanageable proliferation of branches, we worked to make sure that choices could change the tone of the experience yet converge back to the main storyline. We experimented with techniques like requiring multiple locations to be visited before opening the next branch to ensure that players did not miss key parts of the narrative.

THEME

Being able to draw from the nostalgia and fan adoration associated with Avatar: The Last Airbender was a huge factor in the creation of this game. One big challenge that our team faced was determining what kinds of feelings we wanted to evoke with our use of theme. One big factor in the decision not to make a pokemon-style game was that it made the game feel like a fun, nostalgic experience, rather than the emotionally impactful series of decisions that we wanted to facilitate.

PLAYTEST VIDEO

Click to watch a 20 minute, unmoderated playtest here.

KNOWN ISSUES

We are aware of the pink/purple link issue and attempted to fix it, but after hours of troubleshooting we could not find the cause.

The CSS-styling for the Harlowe version we used for development has not been consistent. Harlowe makes it nearly impossible to meter text or make passages appear incrementally, as well as have music play across multiple scenes. If we were to do this again, we would use Sugarcube in any future development.

CONCLUSION

We feel as though we have grown greatly in the process of making our game. Initially, we struggled a lot with making a Twine game that would be as much a game experience as it was a narrative experience. Throughout our iterative process, we were able to successfully find ways to give players agency while still keeping them on the main story arc, as well as doing so without excessive branching that would complicate later parts of the game. We were able to use a few choice variables that would actually influence later parts of the game without creating separate branches, and this can be seen with the propaganda posters where Zuko can be rewarded later in the game if he does spread them around the town. One of the harder things for us to improve was removing trivial choices and making sure each choice meant something. However, we made some of our initially “trivial” choice points meaningful by giving the text a sense of urgency and telling more about the world around the player and by giving others more meaningful effects on the future of the story.

Looking to the future, we would ideally develop the entire world of Avatar, more or less following the canon of the show while maintaining at least one other storyline where the player chooses not to follow canon. This game would then culminate in one final decision that sets the course of the last chapter of the game to either join Aang as canon dictates or join his father to fight Aang. These would dictate two main endings for the game, one where an “evil” Zuko is defeated by Aang in the final battle and one where a “good” Zuko defeats his father and joins Aang. There would be a third option for ending depending on how the player plays the game. For example, if the player primarily makes “bad” decisions throughout play but tries to join Aang at the end, then they will get a third neutral ending where they can only watch the canon play out before them without participating in the story.