Tiny Room (full name on Google Play store is “Tiny Room Stories Town Mystery”) is a mystery puzzle/escape room type game developed by Kiary Games. It is available for mobile, both Android and IOS, for desktop on Steam and for the Switch. I personally played it on an Android. The game seems to be suited for a wider range of audiences, there are no outwardly scary mechanics such as jumpscares, with only a few snapshots of firearms that the player cannot interact with. The mechanics of the game are very minimal, mostly point and click and swiping motions, so there is no need for familiarity with controllers or game mechanics when player start up the game. Some of the puzzle do include some more advanced logic, but rarely more than about a 5th grade level math.

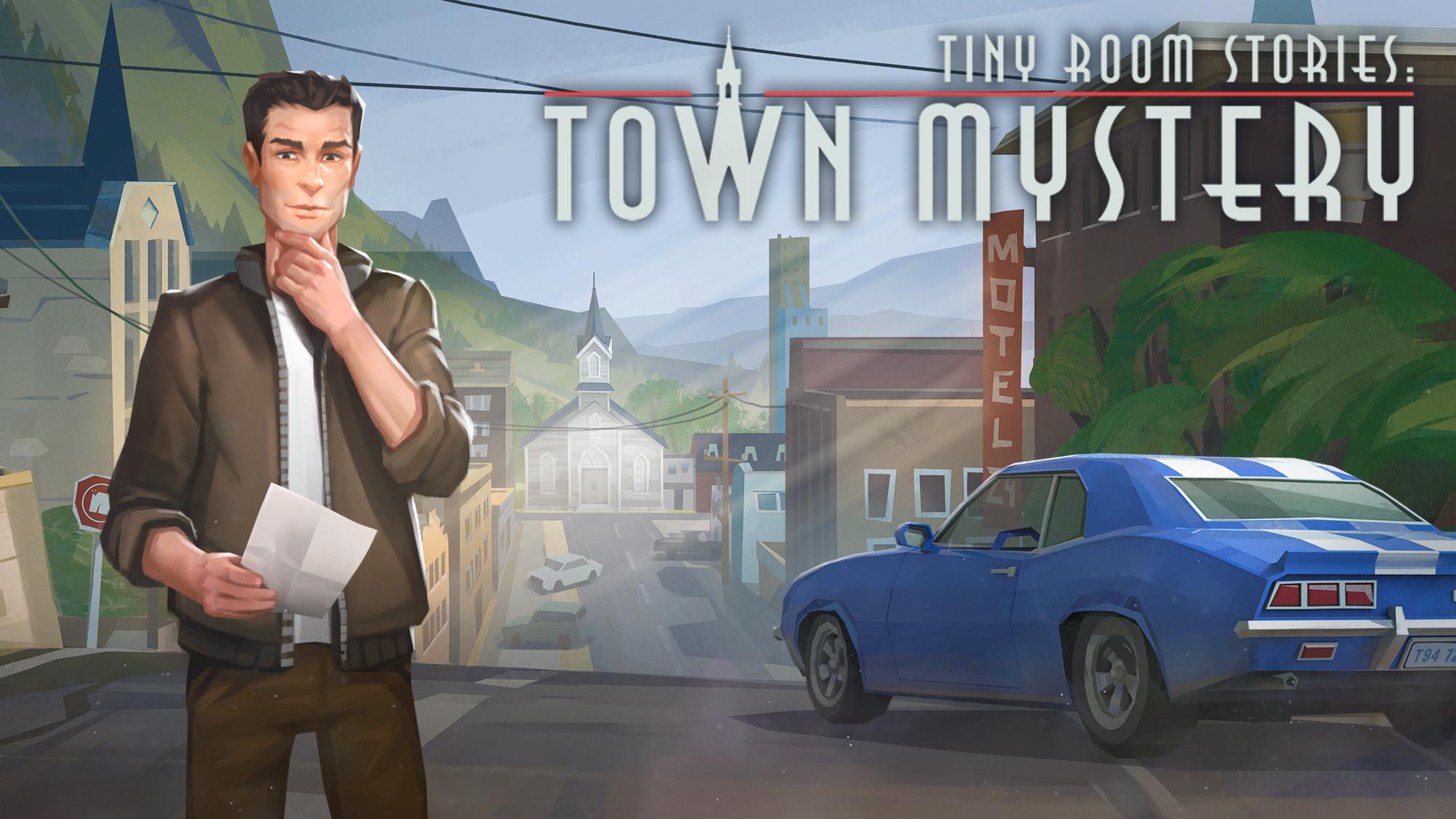

Tiny Room presents its embedded narrative through simple and approachable game mechanics that appeal to explorer player types, including those with little to no digital gaming experience. The game has one overarching embedded narrative: you get a message from your father asking you to come see him urgently. (fig. 1) When you arrive to the nearby town, everyone is gone. Through the very constraint spaces and mechanics of the game, the embedded narrative slowly reveals itself. In fact, you as the players are pivotal in discovering the narrative through the playing of the game.

Fig.1. Screenshot of Prologue

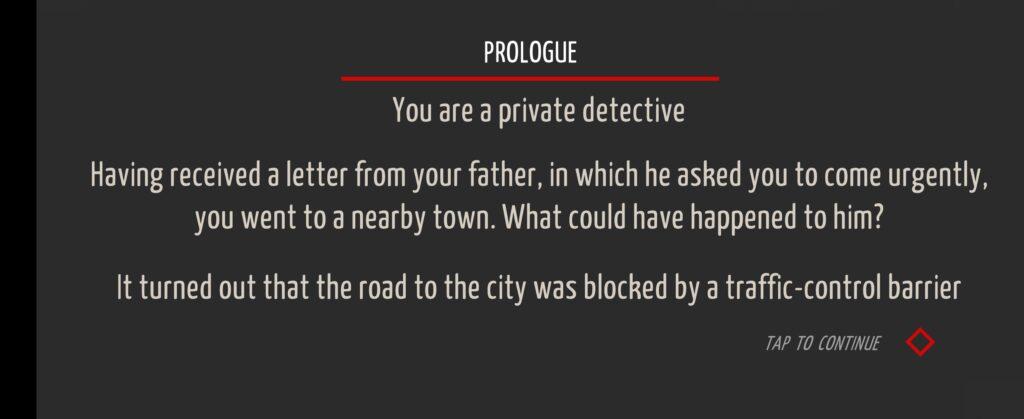

The main gameplay happens in tiny rooms like the one seen in fig. 2. The player mostly can rotate the room and click on objects to get closer looks. The player can also open doors, blinds, drawers, and cabinets. One design detail that really drives the player’s psychogenic need for information, namely exploration is the fact that players can interact with and explore details of the game that do not include any clues. I think that can be the downfall of many escape room/puzzle type games, you can often only interact with the puzzles. In Tiny Rooms you can interact with everything, making this a great game for explorer players.

Fig. 2. Screenshot of a room in the game

This game really exemplifies the principle talked about in the Extra Credits video. The game mechanics are very simple, providing practical solutions to real world limitations. You can only view the room from one angle. You can only interact with some objects from one or two angles, otherwise you are prompted to switch angles with a toast. By limiting the number of actions the player can take in the game, and by limiting the scope of the visual design to one room at a time, the design team was able to focus on an extremely well-crafted embedded narrative for players to discover. While puzzles are certainly part of the game, they are not the main mechanic driving gameplay and narrative crafting forward, exploration of the space is.

There is one main arc in the game, which I admittedly have not fully uncovered yet. After finishing a level (which is contained to one building/location on the map), players get visual feedback of where in the story they are in the form of a book (fig. 3). This detail makes it clear that uncovering the embedded narrative is the goal of the game, while also providing players with a sense of achievement.

Fig. 3. Screenshot of the chapter reveal at the end of a level

While the narrative is being driven by exploration, the game also over constraints in the form of dialogue boxes to the player. These constraints (fig. 4) help the game match an optimal level of challenge, difficult but not frustrating (as mentioned in the competence aspect of Self-Determination Theory) by offering some structure to the exploration.

Fig. 4. Screenshot of “There is nothing of interest” screen

From a designer perspective, this game is a masterclass in embedded narratives and how to use very limited resources to create an incredibly pleasant game experience. The one downside I have found so far is that there is a slight technical breakpoint in the way that rotation of the room works. The swiping motion is often not well detected and is a bit clunky, which did incentivize me to stop rotating the room. I think this did slightly take away from the experience, but it also taught me that while designing a game the seamlessness of the important mechanics needs to be prioritized.