For this week’s critical play, I played A Dark Room, a mystery indie game developed by DoubleSpeak Games. Considering its darker themes, the target audience for this game is likely adolescents and older who enjoy text-based narrative games. With its embedded narrative delivered through a text box that updates the player with new information as they progress, the game guides the player through constructing a town, exploring the wilderness, and escaping to the protagonist’s home. With its limited number of mechanics, A Dark Room feeds its player the story’s narrative piece by piece, slowly allowing them to uncover the post-apocalyptic world they’re in. This purposeful lack of information strengthens the mystery at the heart of the game. Furthermore, the game’s expanding setting grants the player autonomy as the game progresses, allowing the unraveling of the embedded narrative to occur at a more variable pace as new areas are unlocked.

More Questions than Answers

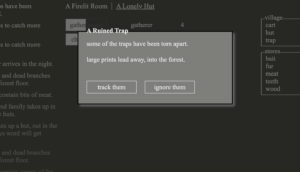

A Dark Room uses a frequently appearing state mechanic to slowly guide players through its embedded narrative through pop-ups that present them with strange, sinister, and random events. By drip-feeding elements of the story to players through this mechanic, the game intentionally leaves the player with more questions than answers, hinting that there is a mystery the player must solve beneath the surface of a text-based survival simulator. In my blind playthrough of this game, it was brought to my attention that there might be more than meets the eye when my character started setting down traps for the first time. While the traps worked to collect fur and meat at first, I was surprised when a box of text (Figure 1) appeared on my screen, notifying me that a creature with large tracks had destroyed the traps. As the game continued, these notifications became more sinister, warning me of silent figures at the edge of my vision and noises in the walls. None of these surprise story points ever became clearer, leaving me worried that I would finally be attacked at some point. In a game mostly comprised of collecting resources and growing a village, these pop-ups break the user out of the submission play they’re used to and present them with bits of narrative, hinting at future discovery. However, the questions introduced by the random events are never truly answered, and while the player’s psychogenic need for information is activated, the game leaves their questions about invisible threats mostly unanswered. As more of these events occur, the mystery surrounding the threat to you and the town is heightened, and the player continues exploring the world in search of answers, finding the game’s embedded narrative in the process.

These events were exciting in the first hour of my playthrough, breaking through the monotony of resource collection to remind me that there was an unseen threat to my little village. Still, as the game presented the same pop-ups frequently over time, they lost their suspenseful effect. Without any payoff, these threats start to feel toothless, and while they serve the purpose of creating mystery, they fall flat once the player realizes they are empty warnings. To improve upon this, the game designers could leverage the player’s need for information while providing autonomy, allowing them to interact with these pop-ups in different ways as more of the mystery is uncovered. This would still encourage players to advance through the narrative in search of the answers to the pop-up mysteries, but their adventure would provide some kind of payoff from this mechanic, even if it’s just a new interaction that leaves the player with more questions than answers.

More Settings Mean More Autonomy

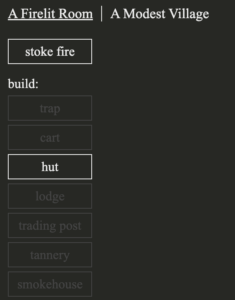

As the game progresses, the player moves out of the dark room and into new settings, each offering the player new mechanics that give them more control over the main character and, by extension, the story. In my playthrough, I made it to the game’s last level, discovering the architecture of the narrative’s various text-based settings (Figure 2).

The first room, even as the story progressed, only allowed me to click on a few actions, and the game would perform them automatically at a fixed rate, so I could only proceed in the story at the speed of the loops in the Firelit Room (Figure 3).

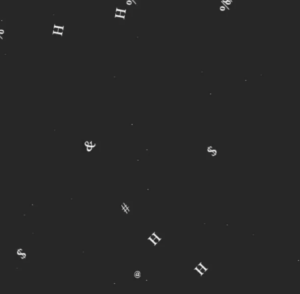

The second setting allowed me to adjust the number of workers in each profession and collect certain resources at my own pace, another loop. The third area allowed me to explore a limited wasteland map to unlock new resources, a third, less structured loop. Finally, the Starship let me enter the final level, a bullet hell that would end the game if I survived; this was the culmination of the main story arc (Figure 4).

With each setting, the player is given more control by discovering new mechanics, allowing them to decide the speed at which they experience the narrative arc. In the first two areas, the player can only experience the story as quickly as the fixed rates of actions allow, while the player’s actions in the final two levels directly impact the speed of the narrative. This is a particularly clever design choice, as it allows for different kinds of emergent fun depending on any given player’s profile. If a player wants to experience challenge, they can fight every creature in the wasteland for as long as they like, and if they want to explore, they can uncover every story the map offers. Player autonomy increases as the narrative progresses and new levels are unlocked, eventually culminating in the player’s ability to decide when the game ends. With these setting expansions, players can fulfill any combination of their need for information, achievement, domination, power, or materialism. Ultimately, the architecture of the setting does not control the story. Still, it creates an environment that allows the players themselves to decide how much of the story they want to experience and for how long.

However, the first two settings of the game comprised the first two hours of my gameplay, making me feel like I did not have enough autonomy in the story. I caught myself wishing that the more mundane loops, like stoking the fire or gathering wood, could be automated as I started exploring the wasteland or fighting monsters. This design choice to increase my autonomy over each new level gave me a strong sense of control and progression, but I still felt shackled to the loops that took a fixed amount of time to complete, like the one in Figure 5.

Even if this decision was purposeful to keep the player grounded in the main setting of the story, the “dark room,” it often pulled me out of the narrative and mystery of the other settings. The loops of completing maintenance and collection objectives worked at the beginning of the game to introduce the setting and narrative architecture by introducing new elements and resources over time. However, as new loops were introduced, such as stocking up and exploring more of the wasteland, old loops should have become simpler to complete. Rewarding the player for taking their time through the later levels by granting them automation on earlier loops would likely resolve this problem and allow players to focus on the main story arc in the game’s third act: returning to your home planet. Players who take the time to explore and discover the world’s mysteries could find NPCs who might perform the more repetitive tasks for the player. Exploration and discovery would thus be encouraged, but not required, to enjoy the setting and story at a slower pace.