For this critical play, I played Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture on PS5, a narrative-driven walking simulator by The Chinese Room. The game’s target audience is those who love story-based games or those who enjoy exploration, since the game centers on a player who walks around a town uncovering a narrative.

Narrative is woven into the mystery through the game’s deliberate choice to have a slow walking exploration speed, orbs of light that guide the user through the desolate playspace, and intractability with the environment with radios, doors, and orbs. The playspace is designed to be completely open so the player can explore whatever they like except for the observatory, which serves as the bookend for the story as well as the key for the narrative. As for loops and arcs, the game has a core loop that repeats itself throughout the game: explore, interact with lights, explore, etc.

As you are dropped in this small but mighty open world, you are confronted with practically nothing other than the fact that you are presumably completely alone. As you walk around, the slow pace forces the player to take in their surroundings and feel just how empty this world is that you inhabit. Much like Dear Esther (another game by The Chinese Room), your slow pace makes you take in the world much like an amusement park ride with a steady tick, except you as the player still have the agency to travel wherever you like and experience the mystery at your own terms. By having a slow walking speed, you are forced to look at every detail in the environment, from quarantine posters to abandoned cars, which further immerse you into the story and make you wonder what occurred in this village.

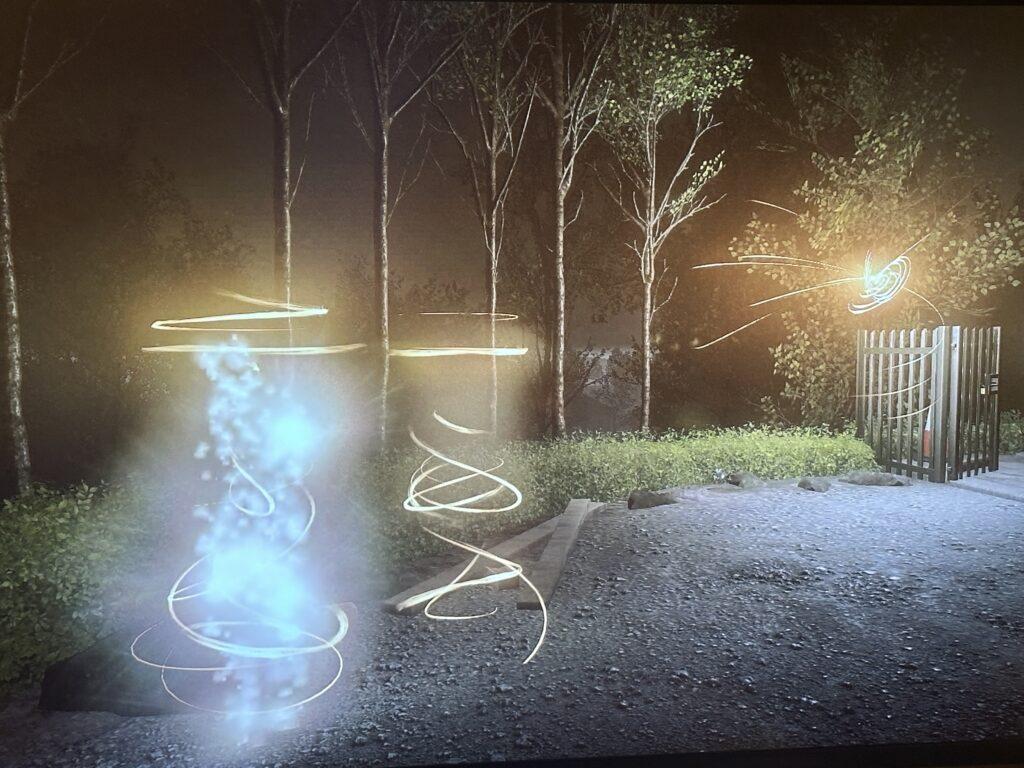

However, you soon realize that you are not completely alone, and are in fact accompanied by floating orbs of light that travel across the landscape. These orbs do not speak, but when they stop moving the player is allowed a cutscene that reenacts something that happened in that very space. In doing this, the designers turn the empty playspace into a stage that pieces the narrative together one vignette at a time. And when the players know now where to go, the orbs are never far away to guide the player to a new vignette. By having the orbs guide the player, the mystery is unveiled at a steady pace and the player is never completely alone, but the feeling of isolation still persists.

Finally, the intractability gives the player the ultimate narrative tool to explore a mystery. I found myself clicking and interacting with nearly anything I could get my hands on. This mechanic plays on the human desire to know what is going on, and to do anything to gather more information for the brain to chew on. By clicking radios and exploring houses through doors, I felt as a player that I held agency and autonomy over the story, and could explore it in any way I wished.

The architecture of the playspace also contributes to the mystery. Starting at the observatory but unable to enter, you are left wondering what happened there throughout the game, with other players alluding to the story. As you explore the space, with natural pathways carved in between landmarks, you are led delightfully and easily along a narrative that you can uncover. This open world exploration dynamic emphasizes the exploration aesthetic and makes the immersion of the world that much deeper.

Finally, even though this game feels complex and emotional, it really only has one core gameplay loop: explore, find orbs, interact with orbs, repeat. The whole game consists wholly of the player walking around this small town and interacting with vignettes of the villagers to piece together the story. However, even with this simple architecture and no other players to be seen, the game succeeds in telling an enthralling mystery that begs the user to poke around and interact with everything to get the full story.