Love Island The Game

created by Naima Patel, Rachel Liu, Julia Rhee, and Parthav Shergill

Artist’s Statement

Oftentimes, ridiculous, unfathomable situations create new friends, or bring old friends closer than they thought was possible. A popped tire or unexpected layover are rife with opportunities to truly break the ice. We wanted to create a game that breaks the ice for its players, giving them the excuse to lean into their creativity and create an authentic experience, one that they’ll continue to talk about well after they have packed away their cards and put away the manual. Doing so allows players that are strangers, close friends, and anything in between to get closer after having played. To that end, we came up with Love Island: The Game (LITG).

At its core, LITG is an improv game. Drawing on our analyses of social interaction and judging games for our critical plays, we hypothesized that players can form bonds and get closer to each other outside the traditional ‘getting-to-know-you’ format. We think that it is less important to ask revealing questions, and more important to implement mechanics that construct a corpus of shared memories and experiences as the basis for a relationship that lasts well past the end of the game. LITG is our attempt to create a game with mechanics that encourage players to develop a fictional persona within our game’s ‘magic circle’, which serves as the vehicle for aesthetics of fellowship, narrative, and fantasy that lead to humorous interactions and newly-forged friendships.

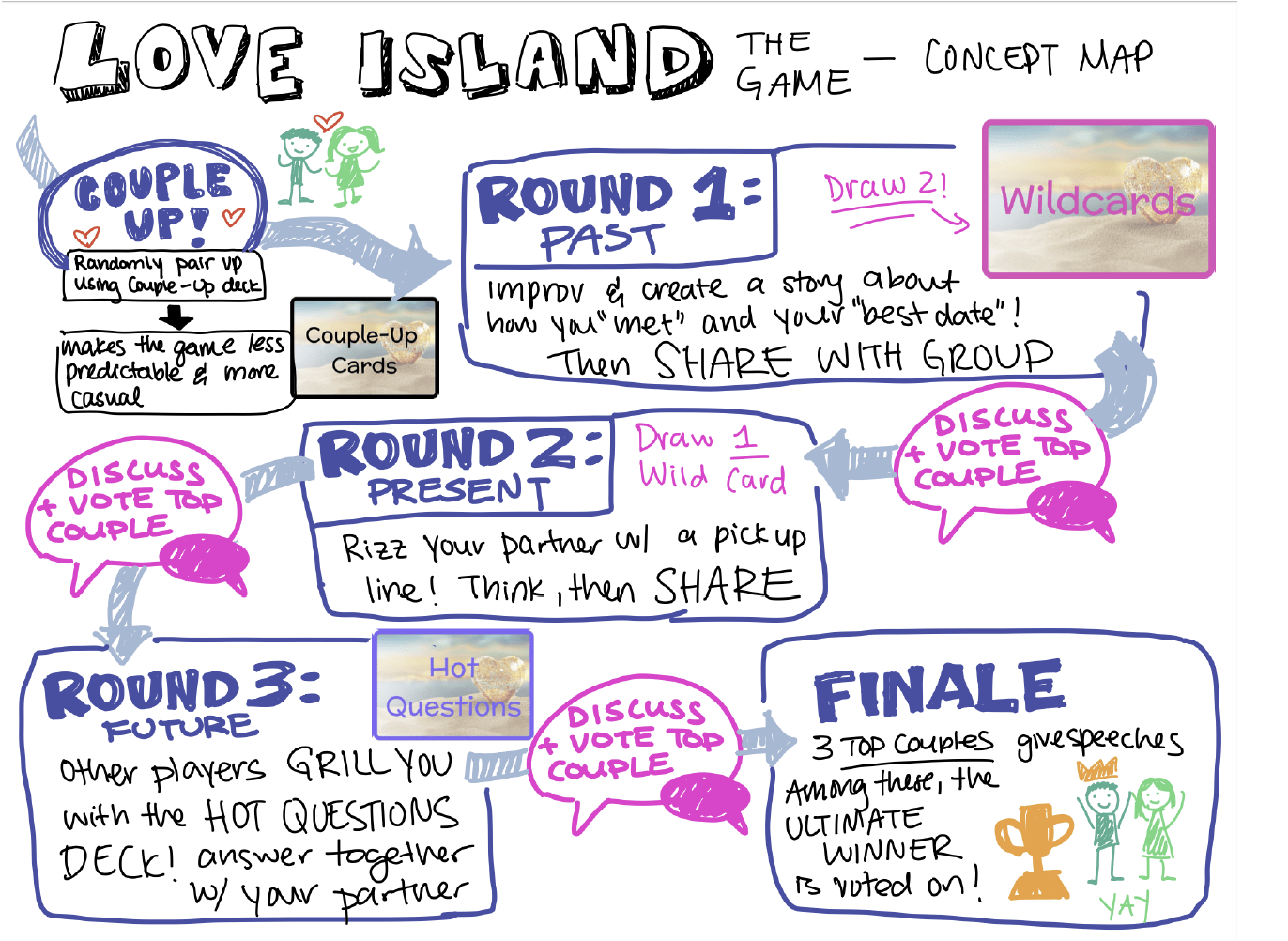

Concept Map

Initial Decisions (about formal elements and values)

Values

As described in our artist’s statement, our primary goal was to create a game that breaks the ice for players, giving them a space for natural dynamics to grow into friendship. We also knew that above all, we valued fun – we hoped that gameplay would be filled with laughter. To that end, we settled on the following values, key to fostering fun, to inform the mechanics we ultimately implemented.

(1) Creativity: You can’t pre-package creativity and give it to your players. We viewed our role as game designers as giving our players enough structure (and a few zany wildcards) so that they could let their creativity run wild. We hoped that this would ultimately result in the kind of storytelling and gameplay that would be discussed long after the game was finished.

(2) Discussion: Discussion, conversation, and all the social friction that comes with it are often the best way to understand other people. Conversation allows players to showcase parts of their personalities, and discussion allows for fun dynamics, such as alliances and banter, to emerge in a group setting. With this in mind, we sought to foster as many opportunities as possible for discussion, whether through formal discussion and vote sessions, or through wildcards and hot questions that would prompt lively, original responses.

(3) Make friends, not enemies: In the show Love Island, couples are competing against one another. Hearts are broken, tears are often shed, and drama abounds. While we loved the spontaneous banter, silly antics, and bonds formed by the show, we definitely wanted to avoid the heartbreak associated with the island, instead focusing on developing strong friendships between “couples” and creating opportunities for fun dynamics to emerge.

Formal Elements

We structured the formal elements of our game around four key tenets, based on the interactions between elements we observed through critically playing other games in class, and drawing on our own personal experiences playing party/social interaction games. These tenets were: (1) prioritizing multilateral competition between teams, (2) incorporating round progression to get players invested, (3) providing supporting resources to make creative gameplay accessible, and (4) prioritizing emergent fun over achievement of pre-defined victory outcomes.

(1) The decision to prioritize multilateral competition between teams was largely drawn from the inspiration behind our game: the reality TV show Love Island. It turned out that all of us in Team 30 are fans of the show, and after spending some time discussing the components of the show’s format that make it so appealing, we determined that couples pairing up to compete with one another as a unit creates a unique group dynamic that simultaneously sparks aesthetics of fellowship while maintaining friendly competition. We also felt that inter-player competition is a great way to continuously encourage player-player interaction, as players are mechanically coerced into discussing gameplay with each other.

(2) We identified a sense of progression as a highly useful way of increasing player investment in the game over time. In any game where players have to maintain a fictional persona, the game risks having players lose interest due to the effort of maintaining their persona without any avenue for evolution or growth. Think about how many poorly-run tabletop roleplaying games (such as Dungeons and Dragons) end unfinished. The reality TV premise came to the rescue once again here. Just like how each episode of a TV series presents fresh drama and dynamics between characters on a show, we leveraged multiple rounds of a game to place couples and their personas into new settings with new challenges. As a result, players naturally evolve their fictional personas over time in response to the constraints of each round, and in doing so would deepen their personal investment in gameplay.

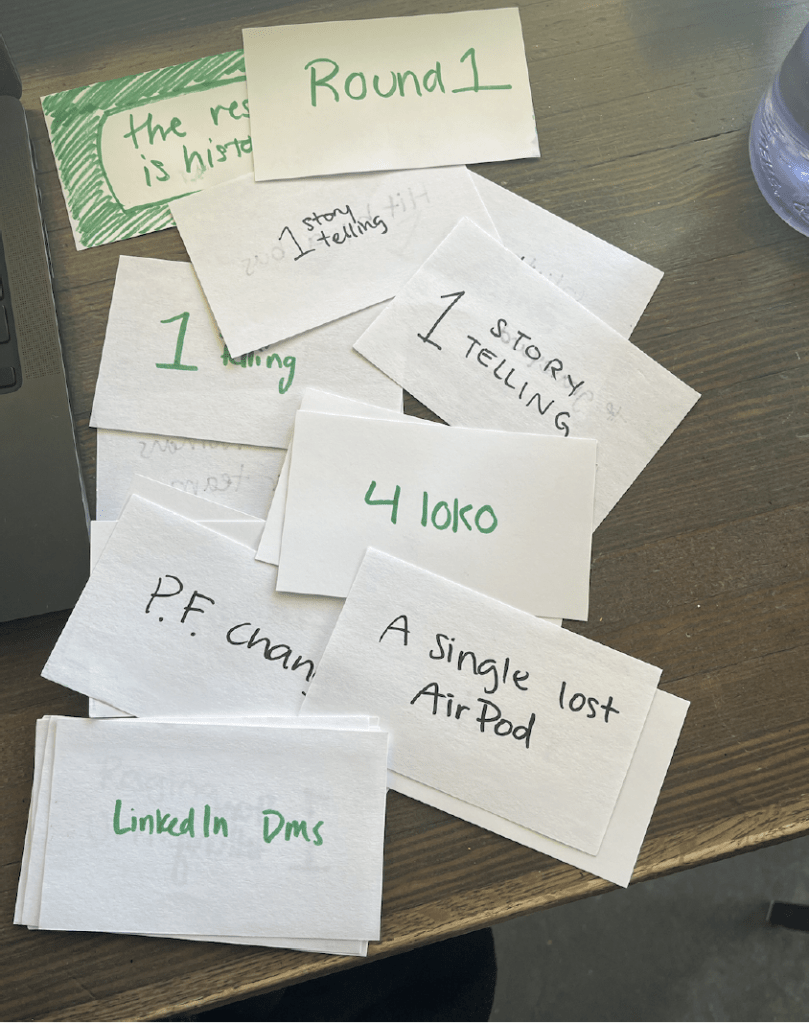

(3) It was not lost on us that such a format for a party game – one that hinges on player creativity and spontaneity – is ambitious. The artistic vision of our game wasn’t just to bring existing friends closer together, but also to facilitate new relationships. In order to enable everyone to be able to participate in the creation of emergent fun through storytelling and social interaction, we wanted to provide players with supporting resources that make the task of being funny a little easier (while also not inhibiting their personal creativity). We brainstormed a number of ways to do so, such as having players crowd-source prompts for questions, before finally settling on providing a deck of cards with phrases and question prompts that players could include in their responses as a way of making the game more absurd and spontaneous. In doing so, we were drawing inspiration from games like Cards Against Humanity, where the most pivotal creative decisions are made by the player, but they do so by acting on resources provided to them by the game.

(4) Finally, and perhaps most controversially, we felt that for our vision, victory outcomes were less important than playtime experience. Playing games like We Are Not Really Strangers made it clear to us that for effective games that create friendships, having victory outcomes that are too prominent can actually detract from the experience. Players of different archetypes (such as Killers, or Achievers) may end up effectively ‘min-maxing’ their fictional personas and losing sight of the inter-player interaction that actually makes the game fun. As a result, we tried to be very careful to create a balanced set of victory outcomes that provided enough incentive for players to meaningfully engage with the game, but also allowed them to feel comfortable playing to have fun instead of playing to win.

Testing and Iteration History

We playtested at least 4+ different times, with CS247G students in class and groups of friends outside of class. Each time, we aimed to include participants who had not yet seen our game. Here, we highlight the 3 pivotal playtests that resulted in major iterations on our concept.

Playtest/Iteration 1: From Get-To-Know-You to Improv

The very first version of Love Island: the Game had the same fundamental 3-round structure, but the rounds had different themes and different prompts. At this stage, the game was less of a cohesive game and more of a sequence of mini-games tied together by an overarching ‘Love Island’ premise. The most important insight we gained from the first playtest was which games in which rounds worked, which were awkward or difficult to understand, and how to bring them together for cohesive gameplay. For instance, our Round 1 game worked exactly as intended – players drew Wild Cards and came up with wacky “best date” or “worst fight” stories. Similarly, Round 2 involved coming up with pick-up lines from the Wild Cards, and resulted in players creating increasingly outlandish lines to try on each other. Here, we realized that the nature of the game was not as much of get-to-know-you as we had previously believed. Rather, players seemed to derive more enjoyment from The cards seemed to be integral in providing structure and setting the tone of the game, and the player’s responses were much more creative and outlandish than realistic.

For Round 3, we had a hand-holding game in which players would line up, and one designated guesser from each couple would feel all the hands blindfolded and guess which one is their partner’s. This round proved itself to be much more awkward – our players reported, “Because I was playing with total strangers, it felt slightly uncomfortable to touch everyone’s hands” and “Guessing my partner’s hand wasn’t really feasible because I didn’t know her, I wish this round was another talking game.”

Overall takeaways involved rethinking another talking game to replace Round 3 – we implemented a Back2Back game, where couples stand back-to-back and point at the person who is “most likely to” in response to crowd questions.

What worked: Players were creative, spontaneous, and funny with the help of the Wildcards. They derived enjoyment from getting into character (as much as possible) and using that as the basis for gameplay.

What didn’t work: The final round was poorly-conceived and the overall gameplay didn’t facilitate as much explicit ‘getting-to-know-you’ as we expected. That wasn’t an outright bad thing – it just revealed that the fun of our game lay in the improv work.

Playtest/Iteration 2: Making it Work

Our second playtest took place in class. We took on a much bigger group than expected (around 26 players!) so faced a number of new challenges, but ultimately walked away with a better sense of what was and was not working. Plus, in retrospect, if we learned what helped 26 people have fun, we could certainly create a game where fewer people would have an absolute blast.

The feedback from this playtest was much more negative than our first playtest. Since the group was so big, and many players were complete strangers, it was daunting for players to be creative, although our players did a great job. Additionally, people felt bad about being voted out (being pointed at by a circle of 26 certainly can’t feel great), and the game struggled to run without a moderator. We often had to interject in order to keep the game running. Tactically, players also noted that our final Back2Back round (implemented in the previous iteration) didn’t make much sense, as the players didn’t actually know “who was more clumsy”. Certainly, they knew each other much better than when they started, but they didn’t have a shared history that made a game like “most likely to” run smoothly. Overall, player spontaneity was much lower than in previous iterations, and potentially negative dynamics in voting were highlighted by the size of the group. Players did note that they had generally had a good time while playing our game and left with new friends. They also commented that they enjoyed the improv aspects of the game, and found that the cards prompted creative, funny responses from their peers: “very funny, it naturally draws up a lot of funny conversations and dynamics with the group. and the prompts on the card are really funny”.

We made a number of changes in response to playtest 2’s feedback. Notably, we realized that voting out a couple each round, particularly in a game that encourages creativity and expression, could inadvertently create negative dynamics in the game. This infringed upon two of our key values — make friends, not enemies, and creativity. As such, we restructured the game to focus on the positives. After each round, the group would vote on a winning couple for that round (instead of the losing couple as in previous versions). During the finale, the couples who won a round would be under consideration for the best couple on the Island, meaning that the pool of potential winners consisted solely of winners of previous rounds. This was a distinction we felt was important in order to motivate players and drive the game forward, while also eliminating the voting out mechanism which could be hurtful and discourage creativity. We also substantially changed the final round. Instead of the original back-to-back game, we changed the format to a hot seat-style questioning. Couples would work together to respond to contentious, funny hypothetical questions about their, allowing for more banter and creativity between the couple and giving the other couples more insight into whether or not this pair was a good match.

Finally, we completely rewrote the instructions for clarity such that the game could be run without the presence of moderators. We also included references to Love Island and “narrative bits” at the beginning of each round to keep the tone light and positive. In this revision of the instructions, we also honed in on the structure of the game, labeling our three rounds as measuring the past, present, and future of a couple.

What worked: The cards and improv aspects continued to be popular despite the scaled-up group size. Players felt that they left having bonded with their fellow players through improvising together.

What didn’t work: The gameplay flow fell apart with a high number of players, and the voting mechanic felt antagonistic. Additionally, the Back2Back final round was not coherent with the tone of the rest of the game.

Playtest/Iteration 3: Love Island Comes to Life

Our final playtest was a huge improvement over the playtest 2! We had each brought two of our friends to play, so each person in our overall group (of 8 playtesters) new only one other person prior to playing – and through our couple-up mechanic, they were partnered up with a stranger. It was very telling that after the game, everyone had inside jokes with each other, and were well on the way to becoming friends with each other despite having just met. All major elements and mechanics in the game went as expected – our rewrite to the instructions eliminated the major stumbling points from the previous playtest, the reformatted final round was far less awkward and actually funny, and finally, the more positive victory mechanics ensured that no one felt targeted or excluded by gameplay. Perhaps the biggest highlight for us was that we were blown away by how creative and funny people were. One ‘couple’ drew the wildcard ‘Teat’ in the first round, which over the course of an hour turned into a cow/dairy themed love story built on their fictional ‘Teat-Cute’ (their pun on Meet-Cute). Another couple immediately improvised one of our favorite pickup lines from round two with the “Obama” wildcard: “Are you Obama? Because you make me Barack hard.” Couples even went beyond the format of the game to bring their personas to life: They came up with ridiculous pet names like Eagle/Poobie for each other and referenced past events from their fictional relationship throughout the game. This kind of crass, silly humor (and the accompanying laughter that followed it) isn’t something we could’ve ever come up with on our own, so it was oddly magical to watch our players bring it to life.

We received feedback for some minor tweaks in the gameplay (i.e. more open-ended cards for Round 3, or implementation of a pet-name ceremony in the beginning). We also realized where further minor rewordings were needed in the instructions when the players stumbled or got confused, and implemented some final tweaks to wording to make the game flow smoothly. Overall, however, player feedback was overwhelmingly positive, which was really great to hear after the work we put in to improve the game after the feedback from the previous playtest. The biggest suggestion we received from our playtesters was that they wanted to play this game again in a social setting – so we are in the process of planning the launch party of Love Island the Game, where we will play the game with some old friends, as well as hopefully some new ones 🙂

What worked: The game was laugh-out-loud funny, the improv and tempo of absurdity and humor was rapid, and the game did not feel boring or drawn out despite lasting around 50 minutes.

What didn’t work: Some phrases in the instruction manual could have been clearer, and perhaps additional equipment aids (like an hourglass and props) could have made the game even more immersive.

Here’s a snippet from our final playtest:

Links to Media and Documentation

- Figma protypes – instruction manual and all card decks.

- Playtest 3 videos/documentation

- Print ‘n’ Play – Print as many instruction manual copies as you like, and print one copy of the card deck PDF (double-sided, so the front and back appear correctly).