This week, I played Deadline, a text-based interactive fiction mystery game. Deadline was released in 1982 for older computers; I played an online port from my web browser. The game was released by designer Marc Blank for the company Infocom. At the time, the game was designed to be played by people with access to computers (less commonplace) who wanted to play a mystery game. Now, the game is suitable for people looking to play an older game or people who want to play a murder mystery type game but who might be scared of the intense graphics or jump scares present in other games in the genre. Based on Bartle’s taxonomy of players, Deadline appeals to players of all four types: “achievers” enjoy the fact that you can “win” the game by solving the mystery, “explorers” appreciate the fact that you get to learn more about a world and a mystery, “socializers” appreciate the interaction with NPCs, including interrogation and finding evidence, and “killers” get to enjoy the aspect of hunting down a suspect.

Deadline allows the player to play as a detective and discover an embedded narrative (a murder mystery) through explorative, text-based mechanics/loops that require the user to think critically about how to solve the mystery, resulting in an overall aesthetic of discovery.

This is a prime example of an embedded narrative: we get to explore as a detective (main narrative) while discovering and learning about a murder mystery (the embedded narrative). Playing as a detective also helps the user satisfy information-based psychogenic needs.

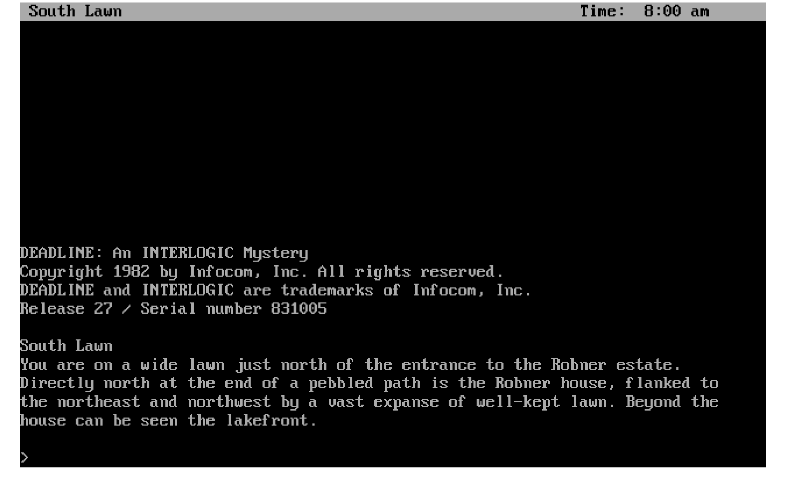

When I started the game, I could see a computer terminal with some information about the game and text describing an initial screen. A flashing cursor is present at the bottom, indicating that I am to type (see screenshot).

Screenshot of the initial screen of Deadline

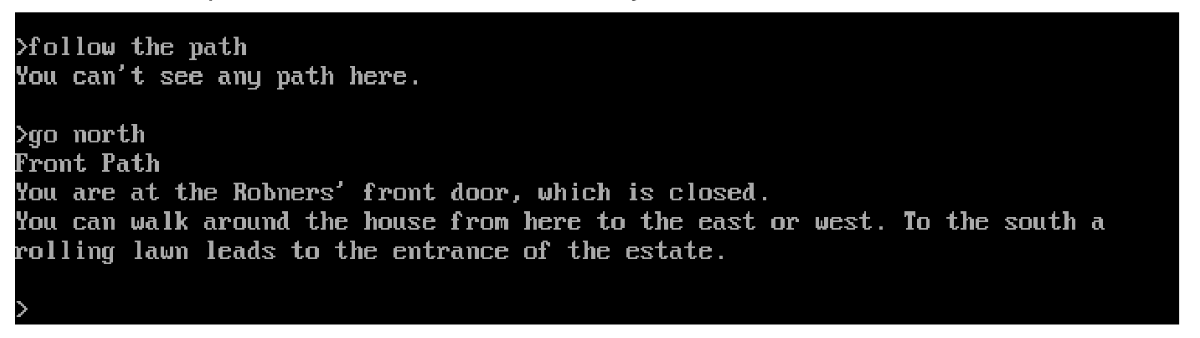

This is an interaction loop. My mental model of terminals and flashing cursors prompts me to make a decision to type something in. I make an action of typing in “follow the path” and am told, “you can’t see any path here” (see screenshot). This feedback made me think that I overestimated the game’s ability to read and understand input text. My mental model when first playing this game is likely informed by engaging with more modern AI/text systems, such as ChatGPT. Thinking critically, I update my mental model to try simpler text: “go north” (see screenshot) appears to work. This same interaction loop repeats throughout the game: you type in a simple command and receive more information from the game (or, sometimes, it expresses confusion or the inability to understand).

Screenshot of trying more complicated versus basic text inputs

After a while, I’ve tailed a suspect and attempt to talk with them (see screenshot) in a more freeform way after an initial curt conversation. I write “talk” based on my mental model of simple commands working well. After receiving feedback about how to talk, I attempt conversation by writing, “SAY TO MRS ROBNER ‘HELLO’” and, “SAY TO MRS ROBNER ‘HOW ARE YOU,’” only to be told that I need to refer to a casebook.

Screenshot of attempting to talk to an NPC

Attempting to determine what the casebook is, I look up the game on Wikipedia and find out that it was originally released together with a physical casebook and some other items (to save digital storage space) that I don’t have access to. This is an interesting hybrid modality of game. In a sense, I still embody the ethos of a detective, using Wikipedia and other internet resources (including online guides) to determine how to progress in the game. The casebook especially is interesting because it can be used for onboarding and providing information to help you play a role of a character and also build your mental model of how to do so (part of interaction loops).

Also evident in my game experience is the presence of skill chains: you need to know how to type and interact to move, talk, and explore. You need all of these things to successfully accuse a suspect given a mode, method, and opportunity.

If you don’t win, the game explains why you failed. If you do, you are informed that you are successful. This is an arc that I read about through one of the guides but didn’t get to experience myself. This is an arc because of the simple actions (reading it/typing to continue) and evocative feedback (an explanation of loss or win). This arc could become part of a loop if you play again from the beginning. But you might not play it again once you win (you know who was guilty)—this links to the reading’s discussion of burn-out.

Overall, we see that the mechanics (including textual input, which is part of a core game loop and also a game arc) and genre result in the discovery of a mystery. This was a fun game to play and figure out, but once you beat it, you’re likely done.