Artist’s Statement

We designed Brainiac to capture the enjoyment that comes with uncovering fact from fiction through deciphering the intentions of family, friends, and peers with the trivia enjoyable by teenagers and above. In Brainiac players compete to convince others—or not—of a certain claim, all the while satisfying various challenges that affect how they are able to communicate with one another. Moreover, we believe that the medium of trivia plays an important role in both enhancing the challenge of the game as well as adding an element of discovery

Most of all, we wanted to make sure that players of all skill levels would be able to enjoy the game equally, a challenge that comes up when designing games that include trivia. Using obscure claims, we ensure that both adults and children can play at once without the knowledge gap interfering. Moreover, we added additional challenges on top of the task of convincing other players of a certain claim. For example, having to “split the total votes evenly” rather than trying to make voters unanimously pick a single side can allow for players to give weaker arguments as part of their plan.

Brainiac has more to offer as the game goes on—for the silly players who commit to nonsensical challenges to the detectives who can read through any facade, we strived to create an environment of easygoing challenge all in small box.

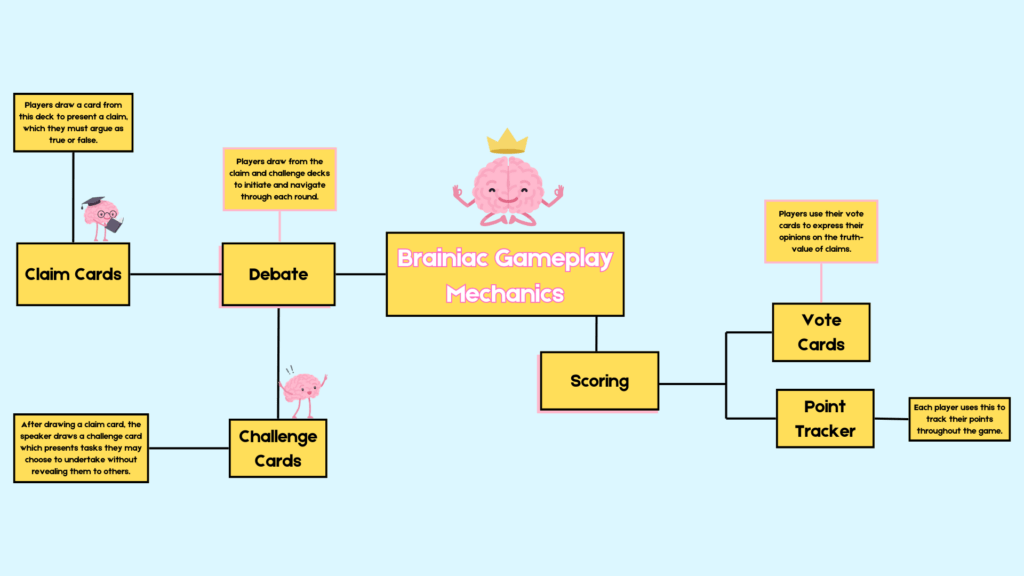

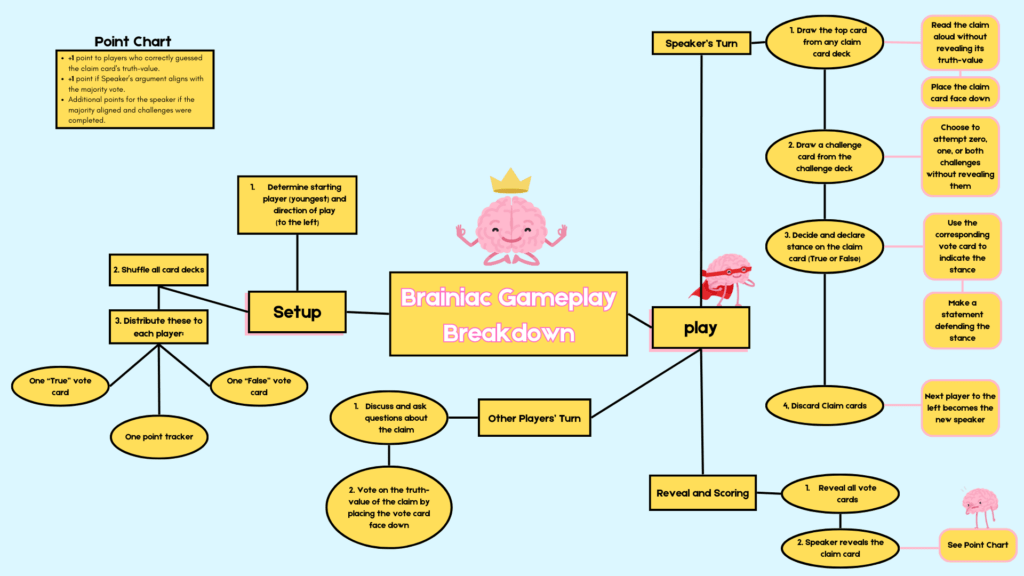

Concept Map

Initial Formal Elements and Values

From the outset, we planned to create a replayable game of social deception that created an enjoyable, light-hearted environment. To this end we focused on a few key elements for our first design: trivia topic cards, role of deception, and additional restrictive challenges.

- Trivia Topic Cards: Initially we thought having players draw topics and come up with their own facts for the game would allow for both maximal replayability and player expression. In this way, each game would always feel different from the previous in that there would be new facts to learn each time that would allow for new arguments and discussions. Moreover, players would always be able to choose a fact that they had more comfortability with which would help to even out the playing field between different players in terms of knowledge.

- Role of Deception: In our initial conception of the game, players were free to choose both whether to come up with a false or true claim as well as if they were trying to convince other players that said claim was false or true. This allowed for four different avenues of deception to approach from which would greatly increase the strategy required for both the speaker and the audience players.

- Freedom of Discussion: In order to produce the kind of light-hearted environment we wanted, we designed the period after the claim and argument were given to be open to any discussion between voters as well as questions for the speaker. We decided not to place a time limit on this section so as to allow discovery of the truth to happen at an easygoing pace.

With these values in mind, we designed our first version of the game as follows.

- Players: Since one player would be designated speaker with the other three voting, we decided 4 players would be the minimum amount to resolve ties.

- Objective & Outcome: The speaker tries to convince the voters to adopt a certain stance whereas the voters try to determine the truth of the claim all to the end of gaining points. In the end, the player with the most points will win.

- Procedures & Rules: The game takes place across multiple rounds in which players take turns drawing a topic card, stating a claim based off the topic along with a brief argument, and having all the voters decide on the claim. After this last step points are awarded based on if the voter was correct and if the speaker successfully convinced voters of a chosen stance.

- Resources: One deck of topic cards

- Boundaries: The game is limited by the number of rounds and the facts and arguments are restricted to the knowledge each player has

Testing and Iteration History

Proof of Concept

Tuesday, April 9

Our fledgling ideas taken form, this prototype tested the effectiveness and overall fun of bluffing about trivia. This set of rules was relatively simple; we had one deck of prompt cards that the speaker would draw from. They would then think up a claim and convince the voters of its veracity or falsity, and it was up to the other players to discuss and vote whether they agreed with the speaker or whether they didn’t. Procedure regarding when players were allowed to vote was limited.

Key Insights

The proof-of-concept appeared successful: players knew many facts unbeknownst to the other, and swapping between true or false was exciting. The prompts, however, ranged wildly from “about cats” to “an unbelievable ‘fact’ about a US president.” This jarring contrast revealed itself as some players had more difficulty creating claims than others.

Updates

To address this last issue, we decided to unify the prompt cards by making them open-ended themes. Prompts now stuck to general categories such as “about humans” or “space facts.”

Justification

Trivia games, in general, suffer from the replay problem, as one that has seen a Trivia Crack question before would probably be able to answer it. High level prompts were intended to address this issue as what the players say would change every game, keeping scenarios fresh.

Open-Ended Prompting

Thursday, April 11

This playtest was done by our team to test uniform prompt cards. The rules remained roughly the same, except the deck of claim cards has been replaced with a deck of prompt cards. There was also a new rule on “fact-checking.” That is, after the voting, the speaker will reveal whether the statement they made was true or false. If any player is particularly suspicious, they “fact-check” them, and if the speaker is found to be dishonest in their judgment, points are revoked.

Key Insights

Undiscovered due to our brief initial playtesting, the prompt mechanic was deeply flawed. The team had made the prompts, but we found ourselves drawing blanks when under the pressure of the game. And although fact checking was a somewhat promising idea, we found that using technology to fact check drastically slowed down the pacing of the game. We could barely finish a few rounds.

Updates

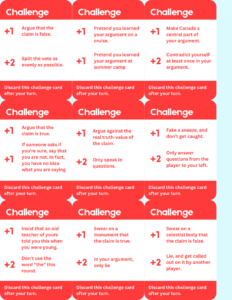

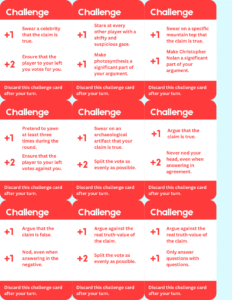

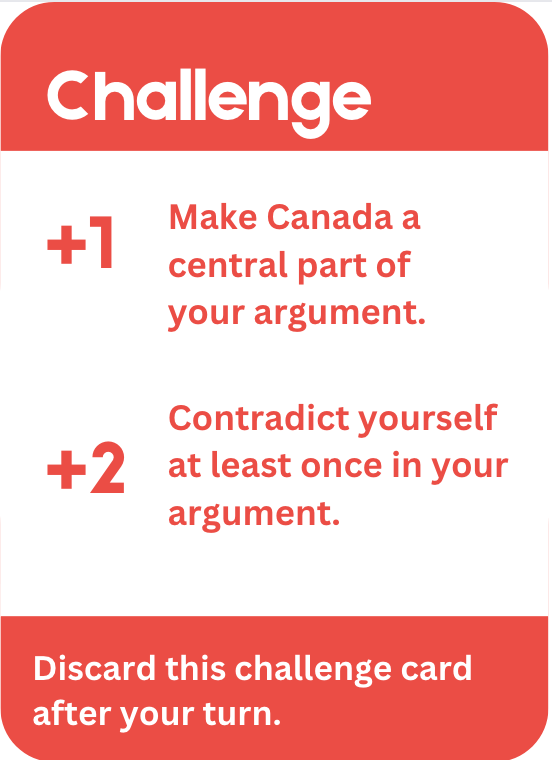

We swapped from prompt cards to specific claim cards, each with a crazy fact or convincing falsehood. We still sought to incentivize the speaker to be more imaginative, so we decided to add a second deck known as “the challenge deck” that speakers would draw from after reading their claim. The challenge cards would offer significant point bonuses if the speaker could both sway a majority to their position and reach certain conditions like “make Canada a significant part of their argument” or “exhibit explicitly suspicious behavior.”

Justification

We did lose the expressivity of the prompt deck and reencountered the replay problem; however, this is not a problem specific to this game. All physical trivia games share this weakness, and we figured sufficiently diversified and plentiful cards would circumnavigate this problem. In the future, a digital version that rotated in new facts would be ideal. Moreover, adding challenge cards would diversify player choices even with repeated prompts. In addition, they could offer novel argument scenarios and incentivize amusing dishonesty. The hope was to evoke a risky argument out of the speaker that would keep people second guessing, something easy to do with the true/false nature of the game.

Increasing Challenge

Tuesday, April 16

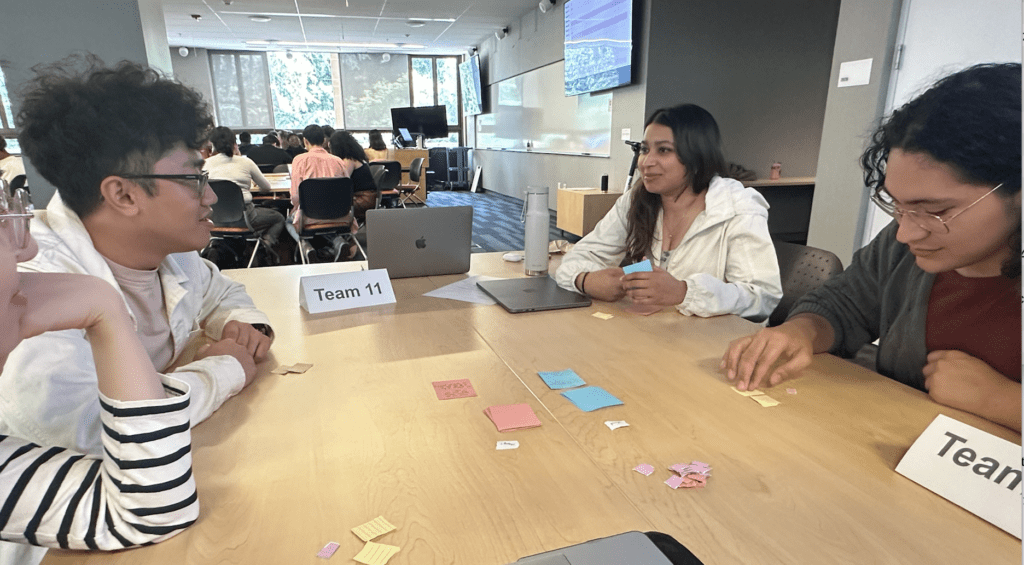

This was our first playtest in class. We had constructed a new deck of challenge cards and additional claim cards with the primary goal being to test how well our challenge cards enhanced the game’s enjoyability. The team was also excited since these tests would have all players ignorant to the trivia on the card. This game had four players and lasted four or five rounds with no definitive winner.

Key Insights

Sometimes players were very out of their depth for the trivia; however, explanations written on the card and challenges guided some pretty crazy—and surprisingly successful—lines of reasoning. There was some tension in understanding the rules: the players were unsure if they were voting on the truth value of the claim or if the speaker was lying, which are theoretically equivalent but still confusing to take in. However, the players overcame their confusion by deciding to vote on the truth value of the claim. Our team was so encouraged to see players having fun.

Updates

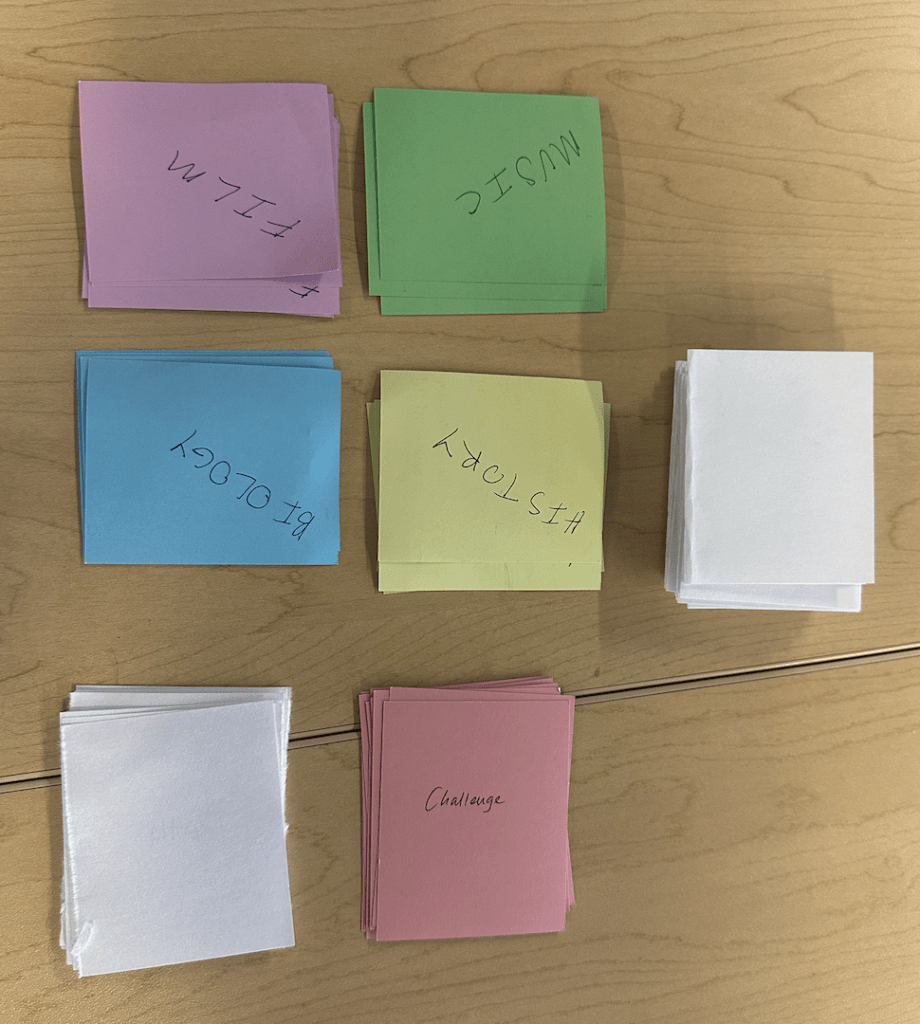

We attempted to update the rules to be more clearly articulated, and we broke the trivia deck into four separate decks speakers could choose from: biology, history, film, music. Additionally, we sought to expand the challenge card idea to voting players and introduce “goal cards.” Voters could complete these goals during discussion to gain a point or make others lose points.

Justification

Although players eventually understood the rules, better articulation never hurts. We also wanted to minimize the stress of coming up with arguments; trivia that was completely random somewhat blinded the speaker, especially if the category of trivia was outside their knowledge. Categories for decks could give the speaker a little more comfort and confidence in their strategy.

The hope for goal cards was to introduce other mechanisms of inducing more exciting discussions. Many goal cards were designed to incorporate questions that encouraged voting players to be deceitful to each other or to ask specific questions of the speaker. This would give the voter player status more complexity, which seemed valuable, as a player is a voter most of the game.

Division of Prompts

Thursday, April 18

This was our second playtest in class. We prepared four separate trivia decks, a challenge deck, and a deck of goal cards that all players would draw from at the beginning of the game for a goal to meet. There were four players, and the game lasted about five rounds with no definitive winner due to lack of time. Players were provided with minimal instruction about game rules since we wanted to test how well our rules were written.

Key Insights

Players were not incredibly enthusiastic about reading the rules. There was a lot of confusion in the game concerning procedure: when did the speaker draw from what deck vs when were goal cards supposed to be collected on. Players appeared to enjoy some of the deception elements of the goal cards, but they expressed concern about their complexity. There were also issues remembering what the speaker’s stance was. Finally, players were confused about what they should be voting on, a similar issue as the previous playtest, but there was less resolution in this run.

Updates

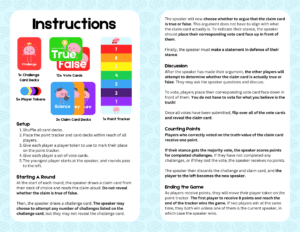

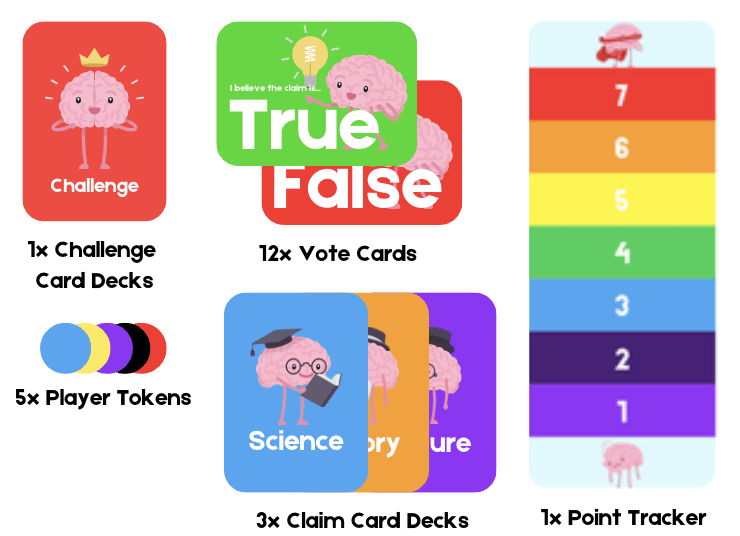

We updated the rules to be perfectly clear what the voters would be voting on: the truth value of the claim the speaker would read. We also decided to reformat the rules in general, including bolded and underlined language along with plenty of pictures in the rules to describe the board. Further, the speaker would place down their vote card designating true or false to indicate which position they were arguing for. Finally, we elected to remove the deck of goal cards from the game and make our four categories into three: science, culture, and history.

Justification

Admittedly, the rules were a bit dense and the lack of pictures was probably uninviting to the eye, so we thought visual cues would go a long way in making the rules interpretable and approachable. The language of the rules was also finally cleared up, so there would be no confusion about the objectives of the voters or the speaker at any time.

The goal decks were removed because of sensory overload. There were so many decks to setup and a lot of overlapping logicing happening at once between the goal cards, challenge cards, and the dynamics that emerged between their card interactions during a round. We wanted voter players focused more on the psychology of the speaker and felt discussion among each other would be enough for their interest. The lack of goal cards also made the speaker a more unique role than that of a voter. Sensory overload is also why we elected to have three trivia decks instead of four, making the categories broader but still roughly delineated by subjects people might prefer over others.

Clarified Rules

Tuesday, April 23

Having now finalized the game materials and mechanics, we were able to have our longest playtests and first full run through. This was a 5 player in class playtest. Player 2 won the game after 9 total turns and 2 turns as speaker.

Key Insights

Having the time to run through the entirety of one game was extremely valuable as we shifted our focus onto game balance. First, we observed that some challenges were easier to accomplish than others. Specifically, these are the challenges which can only be failed if the speaker fails the vote, such as claiming that you learned the fact at a specific time or place. This is in comparison to challenges which can be failed in simply attempting them, such as the challenge to split the vote evenly. Secondly, players expressed that a ~40 minute playtime was too short, as they wanted to each have at least 3 or 4 opportunities as speaker. Finally, we observed that players had the most reactions and “game sounds” when a speaker attempted one of the unorthodox challenges, such as having to speak about photosynthesis in their argument. This element of confusion added much more hilarity than the challenges which asked the speaker to take a specific stance, which did not particularly add to the game.

Updates

In response to this, we adjusted the point values of the challenges so that now, each card does not always have a +1 and a +2 challenge, and most have only two +1 challenges. This also adds an element of randomness, meaning you cannot predict exactly how many points are possible on a single turn. Additionally, we adjusted the challenges to include more unique action or speech challenges and less challenges that ask players to take a specific stance. Finally, we further increased game balance by taking away the 1 point the speaker gains simply by winning the vote, making it so that the speaker only gains points for completed challenges. We believe this will cause two effects. First, players will earn less points per turn. This will lengthen the game, as players will now be unable to win the game in only two turns as speaker. Second, more “action” based challenges will create more moments of fun.

Finally, we cleaned up our materials for clarity and grammar. In particular, we added bolding to the most important parts of our instructions sheet to make it easier to skim. We also clarified that a tie for winning the game is possible, and what to do in case of a tie.

Justification

A longer game with more individual moments of fun will be more satisfying to players and also allow for more development of strategy as each player will be guaranteed more than one turn as speaker and have more time to acclimate to the game. It’s our hope that players will begin to notice patterns and develop more sophisticated styles of play as they are given more leeway to test their ideas when losing one round is no longer as impactful.

Design Elements

Overview

In deciding our design elements, we kept in mind our target audience of teens/tweens and their families and friends. At the same time, we wanted our designs to align with our wacky and hilarious game aesthetics. To do this, we chose to aim for a bright and cartoonish feel.

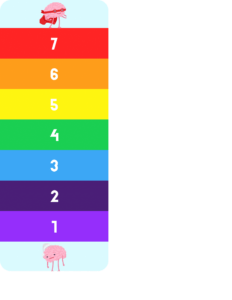

We settled on a set of rainbow colors for our different card decks, both to allow easy identification of each type of deck at a glance and to create a bright but gender neutral theming. To create cohesion between our physical elements which used different colors, we used a brain cartoon with various costumes. Finally, we chose a sky blue which complements all the colors of the rainbow (think of a rainbow in the sky!).

We used three fonts, two title fonts and one body font. The body font is a simple sans serif for readability, and the two title fonts are uneven and cartoonish to align with our design goals.

Additionally, we kept accessibility in mind by ensuring our materials utilize high contrast and do not rely solely on color for identification, a common pitfall for games with strong color based designs like ours.

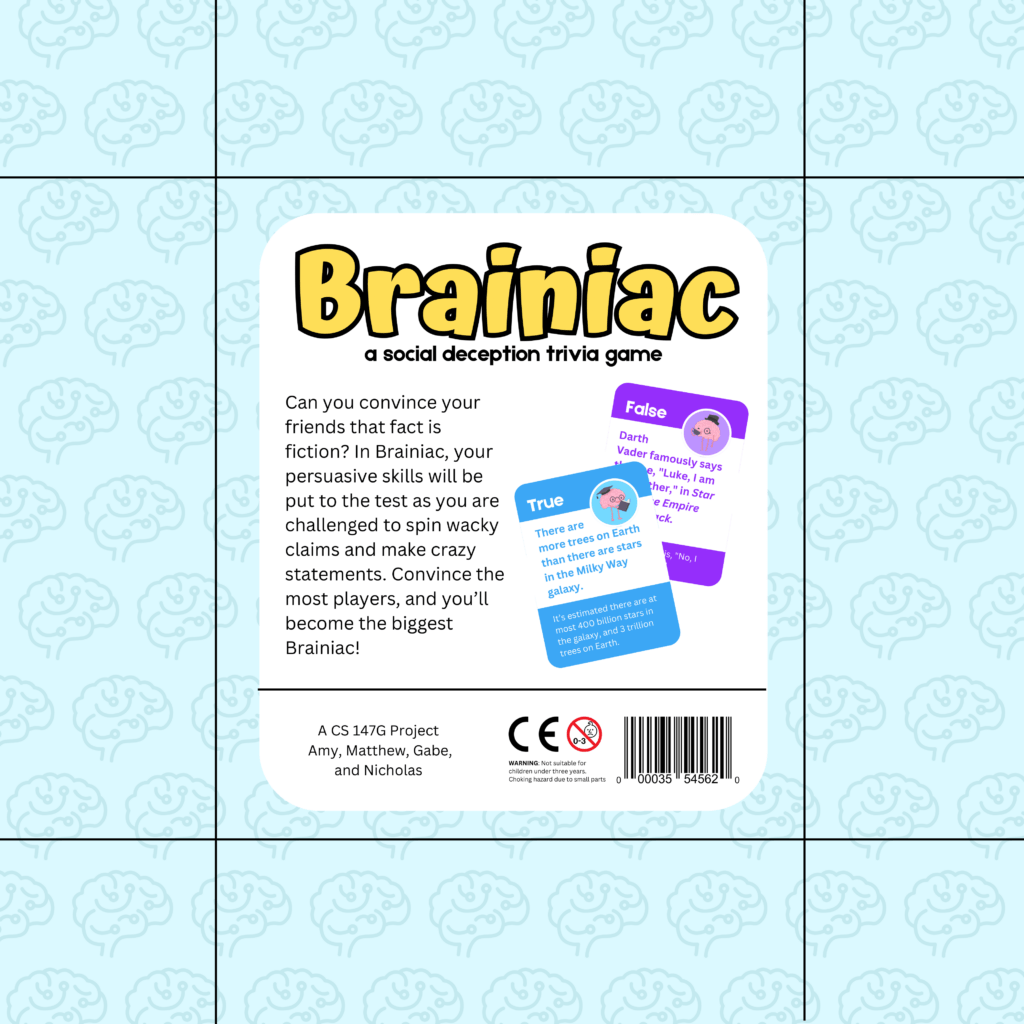

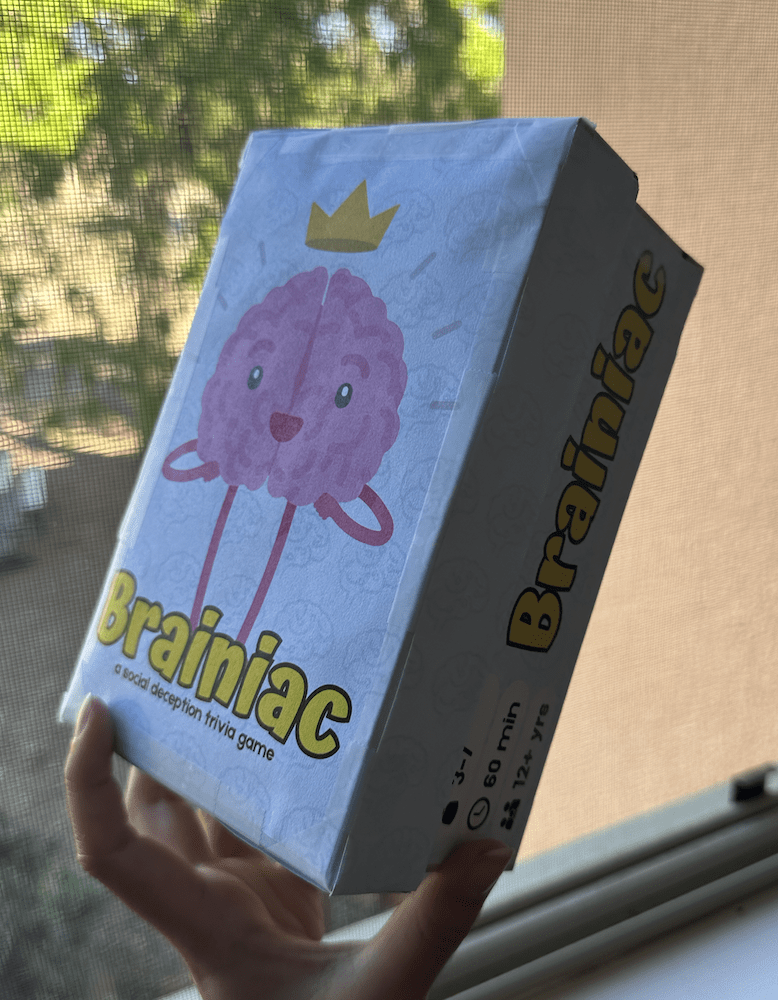

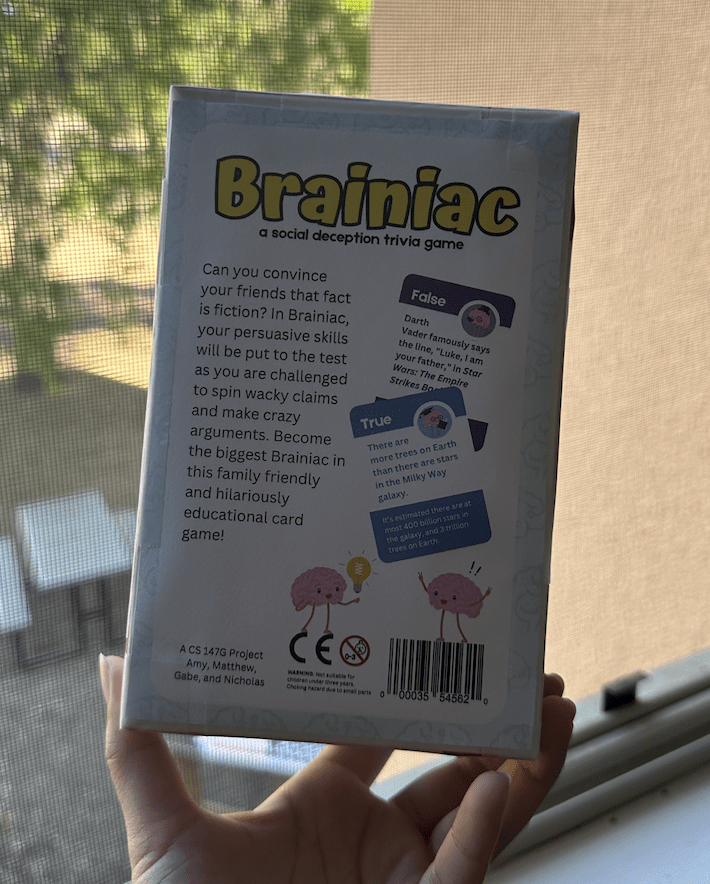

Packaging

As most of our physical game pieces are playing cards, we did not need a large box. So, we chose a small 7” x 4” size to hold all our materials and allow for portability. In designing the box, we were sure to include necessary industry standard elements such as a section for the number of players, age, and play time. Additionally, we included an overview of our game on the back of the box, both in the form of a short but descriptive blurb and previews of some of the cards inside the box. By looking at the box, the player should be able to get an idea of what kind of game they’re buying and roughly how it plays, but not need to bother themselves with specifics such as scoring or when to draw cards.

Cards

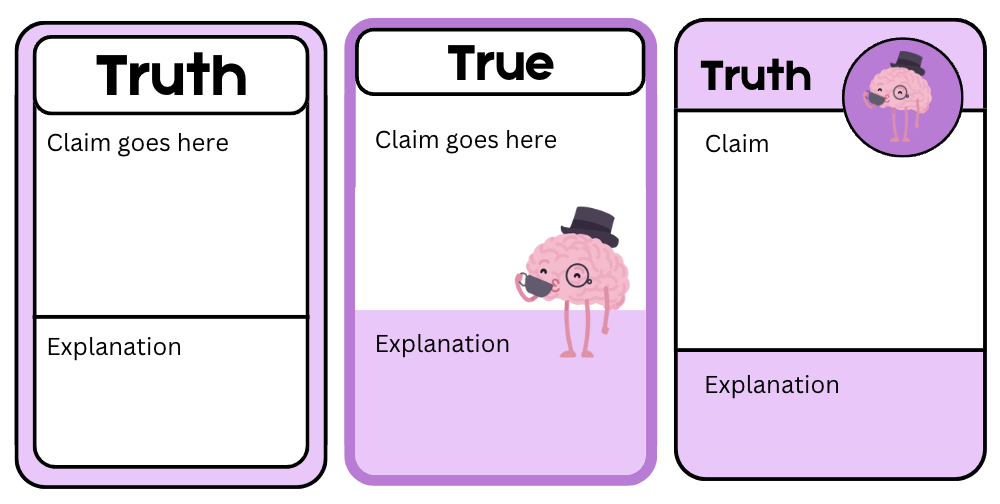

We went through multiple iterations for our primary cards.

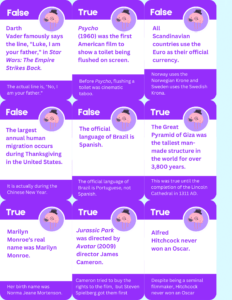

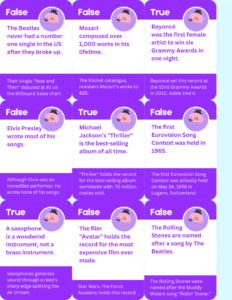

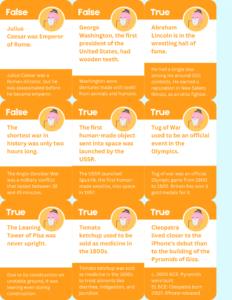

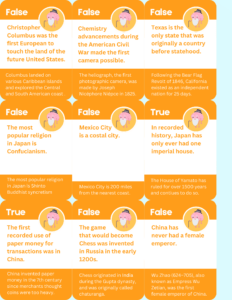

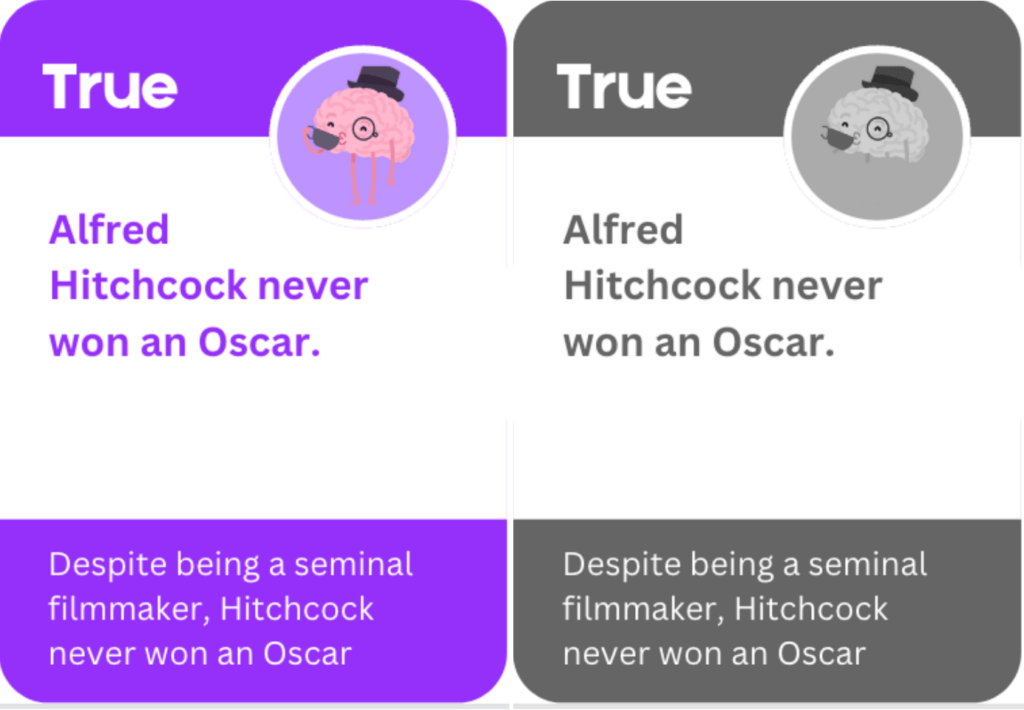

Ultimately, we settled on brighter, more saturated colors both to increase contrast for visual accessibility and to make the cards feel more exciting and engaging. Additionally, we made it possible for players to easily remember which card deck they drew from by using a costumed brain cartoon on the front and backs of the cards. We felt this was necessary to address accessibility, as games overly reliant on color for identification are inaccessible to those with colorblindness. With this simple design choice, it’s now possible to play our game with little to no color vision.

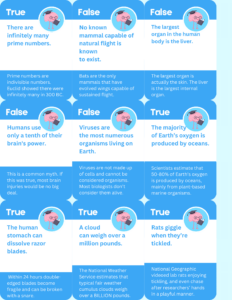

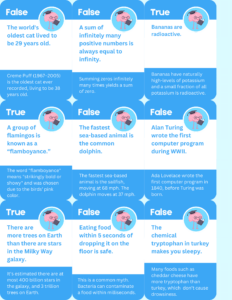

To create visual hierarchy, we kept the “True” or “False” label in the largest font and most prominent position on the card, with the claim following it. By putting the explanation label, which is the least important element, in the footer and on the background color, we help guide players to read the other elements first. Using a different background color also helped ensure players knew that there was a separation, and did not accidentally read the explanation aloud while reading the claim. We found through playtesting that our visual hierarchy was intuitive enough that we did not need to include labels for the different sections. This allowed for a much cleaner design than one which relied on labels.

Notably, our challenge cards do not have an explanation section. Instead, we included a prompt for players to discard their challenge card after their turn, as this was a step players sometimes forgot during playtesting. By conveniently placing this prompt, we further lessen the amount of information a player needs to actively remember.

Citations

All images, icons, and fonts are courtesy of Canva.com.

Final Playtest Video

Final Prototype (Print ‘n Play)

Brainiac Cards Brainiac Extras Brainiac Instructions

Design Mockups