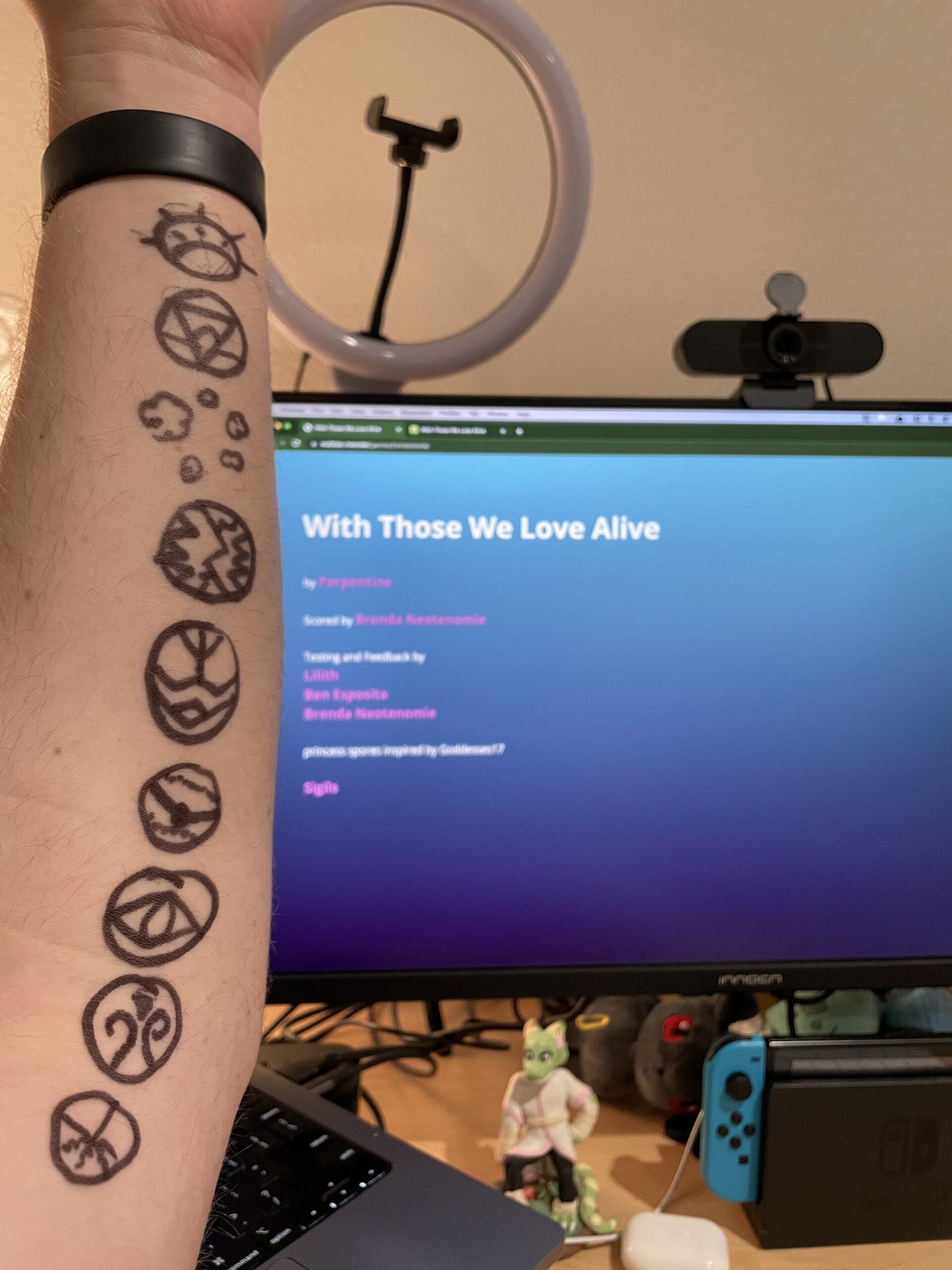

Playing With Those We Love Alive was a weird, uncomfortable, immersive, divergent, intimate, and hopeful experience. Playing it like a feminist meant, for me, being willing to engage and push myself into the experience more intimately that I might if I were playing a game only for fun– of course, we can “turn off” (disengage) from an uncomfortable book or piece of media to gloss over the discomfort, but in doing so you rob yourself of the way media can change you or offer you new experience! With Those We Love Alive explicitly asks the player for this kind of intimacy at the beginning, asking them to draw on themselves (bringing a symbolic, perhaps superstitious link between the events within the narrative, which is dark, and one’s own body).

I think this kind of embodied intimacy is subversive, feminist game design. Mainstream games often exist as portals to disconnected escapism, where consequences don’t matter and the player can kind of do what they want without fear of consequence– but then, where is the call to action? Insofar as games are affective structures– and therefore, feminist games are games whose affect is feminist, where the emotions it instills in the players prompt exploration of the extant power structures and push towards equity– a game that encourages the player to escape into a fully disembodied, disconnected experience can’t possibly be a feminist game.a Meanwhile, this game (and many others– OneShot comes to mind) asks explicitly for an intimate connection with the real-life player. Opening the player up like this invites them into the fiction, and it means that what happens in the fiction (through the mechanics, and the narrative, etc.) to be a partially embodied experience in the player, at least via the empathetic connection the player has with the characters (social/emotional responses are physical responses!). This is where you can get your call to action, in a real, visceral sense– the player can take their experiences “in” the fiction and apply that as a lens through which they can view the real world.

In the case of With Those We Love Alive specifically, the player is asked to embody a trans character who takes hormones, who has experienced some kind of traumatic child abuse, in a dark world, serving an obviously evil, terrifying queen. A sapphic love story is revealed between the player-character and another character, which builds towards the climax of the story, and resolves at the end. Although the story ostensibly follows the “climax arc” that Chess describes as potentially heteronormative-patriarchical, (A) I think that the story itself subverts this so hard as to not be a productive critique of Porpentine’s work here, and (B) even still, the story structure strings the player along in a perpetual up-down that feels as though it might even be endless, until the climax suddenly snatches the player to safety and the end of the game; in this way, it seems to blend the “never-ending narrative middle” with a satisfying and hopeful ending, which reminds me a bit of Chess’ introduction– wanting to be positive without being positivist.

(a) I actually think that it’s impossible for a game to be a fully disconnected experience in the way described here– I think that would require the player to be dead– but the point still stands that designing for disconnection seems anti-feminist. Note that escapism does not necessarily mean disconnection; escapism is a way that many folks connect with a “true” or “inner” identity, for example, or a means to explore an unclear or forming identity, for example, and designing to enable this seems highly feminist to me!