Created by John Altankhuyag, Krain Chen, Star Doby, and Sammy Puckett

Game

Walkthrough

Final Playtest Video

Table of Contents

Design Process

Playtesting and Iteration

Playability

Narrative and Space

Final Playtest Feedback

Final Notes

Design Process

Artist Statement and Key Inspirations

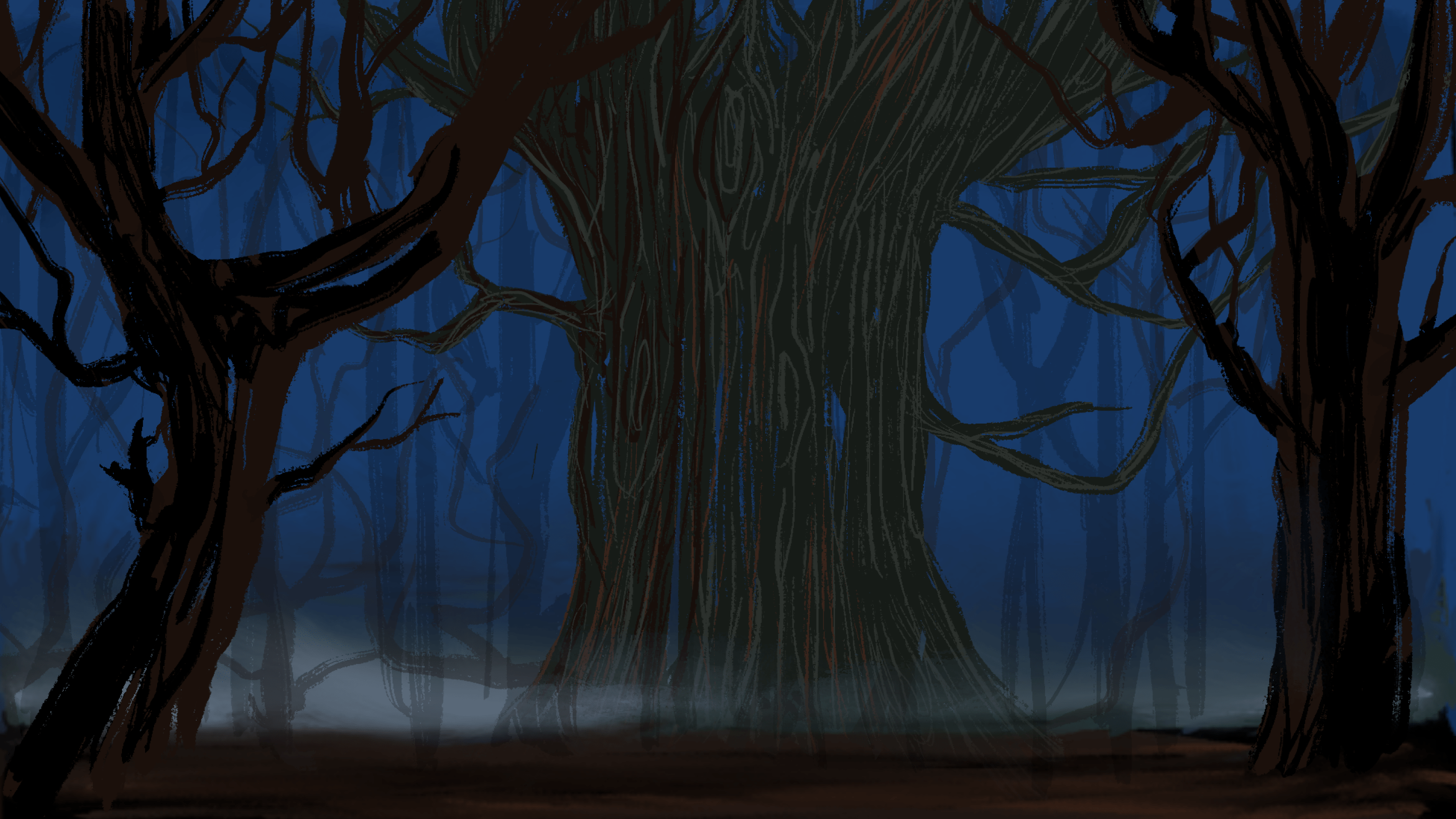

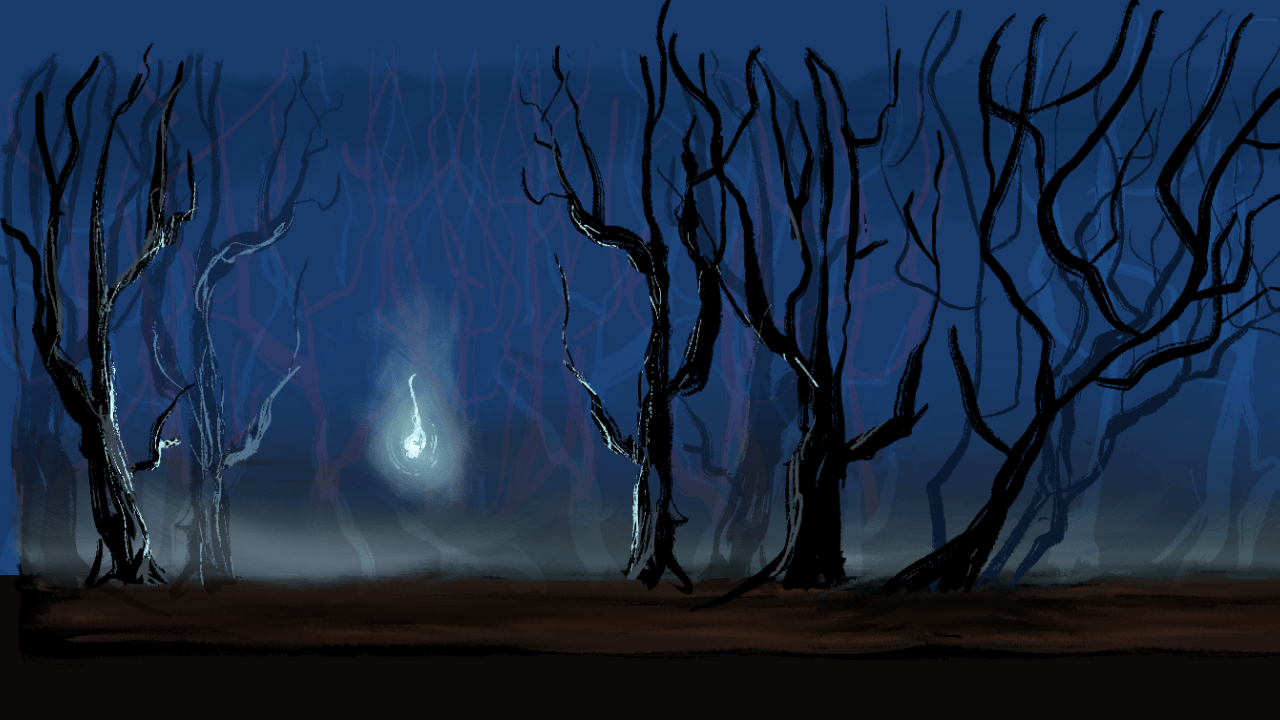

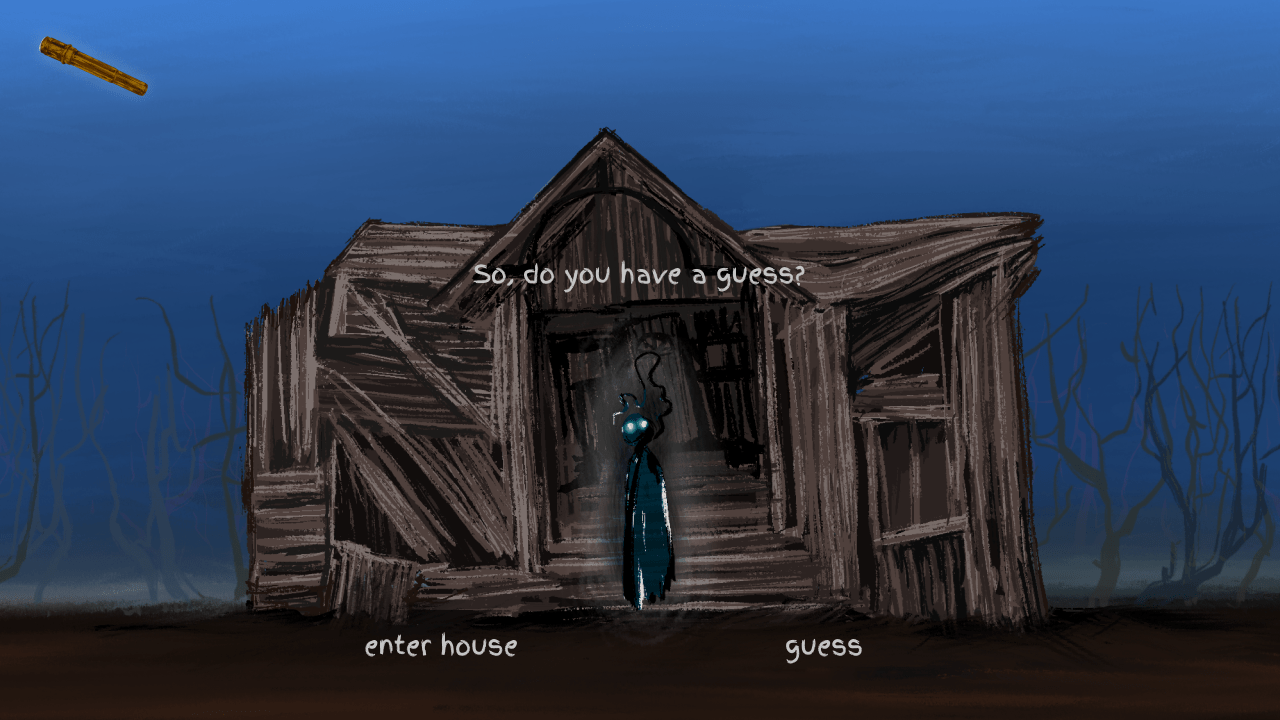

Heartwood is a game about how one can feel lost when confronted with change and growth. It is a point-and-click escape room game in the style of Cube Escape and Year Walk. The game is set in a dense dark forest and the player plays as the story’s protagonist in a first-person POV. As the player navigates this landscape, they solve several puzzles on their journey out of the woods. Just as important to the puzzles, though, is the tone and narrative of the game. To achieve that, we created every visual asset from scratch and embedded the narrative throughout the landscape and objects in the game. Furthermore, the rough hand-drawn textures and cold color palette accentuate the eerie, melancholy feeling of the game.

As the player wanders the forest and solves each puzzle, they journey closer to the edge of the woods. As such, the visual elements of the game progress to become more open and less melancholy or ominous. The trees are smaller and more distant, the sky lightens, variations in scenery become more obvious, and finally, there are human-made objects such as a fence and a house near the end of the game. These are all signaling that the player/protagonist is gradually finding their way out of the forest.

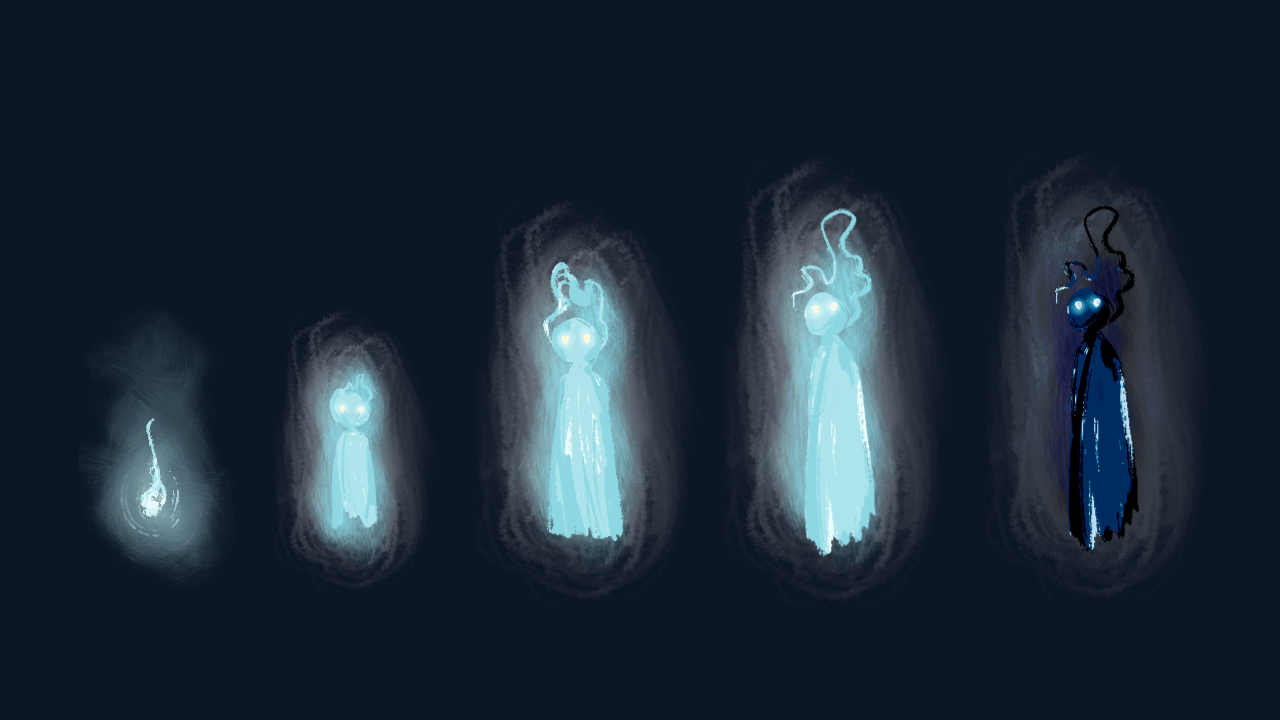

The game narrative also comes through the sometimes cryptic dialogue of the Spirit character, which is inspired by will o’ the wisps in folklore. Other than the player-protagonist, this is the only character in the game. The Spirit has three main designs in the game, as it too grows and changes, with each subsequent design having more adult-like features: longer hair, higher-set eyes, and a longer body. These design changes are also a hint that the Spirit character is actually the child, teen, and young adult versions of the player-protagonist’s past self. The last spirit design, with an altered, darker color scheme, represents the protagonist’s future self, colored eerily to convey the unease of moving into one’s future.

Another key inspiration for the game is Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The Way Through the Woods.” On the surface, this poem is about an old road in the woods that has been long abandoned and reclaimed by nature. The vivid descriptions of the woods that evoked curiosity, awe, alienation, mystery, and despair are the same feelings we sought to put into our game. But this poem could also be read as a metaphor for how growth can mean losing something, and how one can reconnect with their childhood in new ways. Underlining this interpretation, we scattered lines from the poem throughout the Spirit character’s dialogue, since the Spirit is the childhood version of the protagonist.

Finally, we give the player a choice at the end of the game: to stay in or leave the forest. Depending on the player’s choice, either the first or the second stanza of “The Way Through the Woods” is shown on the final screen. The first stanza, corresponding with the choice to leave, ends with “There once was a road through the woods,” giving the protagonist a feeling of satisfying completeness at having found a way out and reconnected with their childhood. But just as importantly, the second stanza, corresponding with the choice to stay, ends with “But there is no road through the woods,” leaving the protagonist in doubt about whether they ever leave, or whether the woods ever existed in the first place.

Target Audience

Our target audience is people who already have some familiarity with and enjoy escape room-style games. To avoid breaking the flow of gameplay and diminishing the eerie mood of the game, we include very little by way of tutorials or instructions. The simple mechanics of point-and-click games should be self-explanatory for our target audience. For elements that may be new to such audiences, though, we include instructions and low-stakes introductory puzzles in order to allow players to ease into gameplay. These elements, once learned, are then presented in more novel, challenging forms later in the game, which allows players to demonstrate eventual mastery and build confidence within this genre of gaming. And for established fans of point-and-click or puzzle games, our focus on a compelling narrative and the lush visual and auditory landscapes of the game provides a fresh take on this genre.

Formal Elements

At the very start of our game, players may feel slightly disoriented. They are not sure who they are, why they are in this dark forest, or what the objective is. But we do not ignore onboarding altogether (see Playability section for specifics of how we onboard). Rather, by blending the tutorial into the game, spreading out the teaching of mechanics, and primarily using passive messaging, we mimic the act of slowly discovering where they are. We also evoke the feeling of disorientation one might feel had they actually woken up lost and with no memory of the past.

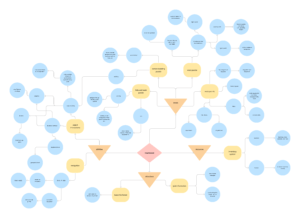

Then, we introduce the forest spirits. The player gets a sense that the spirits want to help them move through the forest, which comes in the form of puzzles. The difficulty of the puzzle corresponds to the age of the spirit they interact with. The child, teen, young adult, and future spirits introduce puzzles from medium to hard, respectively. While solving these puzzles, the player learns more about who the spirits are and how the objects they collect are connected to each other. While designing, we paid close attention to creating puzzles that amplify the theme of the game (i.e. the folktales puzzle comes at a time in the Spirit’s growth when nostalgia about childhood might occur) and which fit the environment (more on that in Sensory Design). We also created puzzles that fit into different categories to maintain the novelty of progress, and these categories include riddles, jigsaw-esque puzzles, sequence puzzles, ordinary or unusual use of an object, and more. The objects are stored in an “inventory” to help the player unlock other puzzles.

Players utilize different mechanics depending on the puzzle they are attempting. The first puzzle mimics hide-and-seek by asking the player to navigate different scenes and find the child Spirit. Clicking the “left”, “right”, and “back” buttons help with this navigation. The scene glows when the player has clicked correctly. In the second puzzle, the player is asked to rebuild a lantern by clicking on broken pieces. Clicking on two broken pieces that fit together will produce a combined piece. The player will do this until the lantern has been restored. The third puzzle is a classic decryption puzzle where the player identifies three mini-scenes, correlates symbols to letters, and uncovers the hidden message. The player can click into the three mini-scenes however many times they like and use text input to enter the message. Lastly, the final puzzle is a combination of the puzzles before. The player navigates through a house to find a missing piece to the spyglass; they restore the spyglass by building it; and finally, they identify scenes to solve a riddle. By the time players reach the end, we hope that they are familiar with all of the mechanics.

Loops and Arcs

Balancing loops and arcs in a puzzle-based narrative game was one of our key design metrics. For loops, we increased the difficulty in each round of a puzzle that had repetitive elements, such as the hide-and-seek puzzle. By increasing difficulty between rounds, we allow the player to build mastery. For arcs, we added dialogue for the Spirit character and a transition screen where the sky gets lighter after every major puzzle. This lets players progress through both the forest and the narrative.

Sensory Design

Visual Elements

As previously mentioned, crafting a strong and unique visual language was central to our vision for Heartwood. We achieved this through consistent color palettes and the transition of the forest from dark to light. We generally used a cool color palette, including for the landscapes, the Spirit character, and even the glowing light of the Spirit. However, we introduced lighter backgrounds and slightly warmer tones as the player got closer to the edge of the forest and the end of the game to create a greater sense of progression. Even so, we used browns and bronzes rather than bright colors and reserved the warm tones for human-made objects such as the spyglass and the dilapidated cabin.

Audio Elements

We aimed to use music and sound effects in order to further the immersive nature of the game, as already created through visuals and mechanics. In particular, this meant using ambient forest-themed music, which not only created the feeling of being lost at the center of a dense forest, but also of the unique blend of curiosity, wariness, and melancholy that we hope for our players to experience. We also placed significant importance on our background music being long and consistent, such that even if the player plays the game long enough that the music loops (which would take around 21 minutes), such looping will not be jarring at all to the player. Additionally, one of our puzzles utilizes sound recognition, for which we tried to manipulate our sounds to be distinguishable and yet mimic realistic sound blends of the forest floor and maintain the air of mystery.

Playtesting and Iteration

We playtested Heartwood with 10 people this quarter. For most of the playtests, we asked people to interact with a prototype on Figma. We provided laptops for those who did not have access to one.

Figma prototype 1.0

Playtesters: Kyle N., Ember F., and Jasmine S.

Our first prototype created on Figma showcased the introduction screens of Heartwood and the first “hide-and-seek” puzzle. We wanted to hear players’ thoughts about the dark forest setting and the interactions with the forest spirits. More importantly, we tested the difficulty and enjoyment of the hide-and-seek puzzle.

What Went Well

- Everyone loved the spooky atmosphere created by visuals

- Appeals to those who love visual novels

- Mechanics matched the narrative

- Gameplay felt “non-intrusive”

What Didn’t Go Well

- Navigation through hide-and-seek puzzle was confusing

- Buttons were not intuitive

- People were easily lost in the map

- Too much mental energy trying to remember hint and navigate map

- Players giving up resulted in clicking randomly

- Finding the spirit was more difficult than we thought

Next Steps

- Add small diagrams in the corner for the hints

- More guidance and feedback from the game

- Add text next to buttons

- Add hint buttons for constant guidance

- Light up area on screen when spirit is found

- More narrative in the beginning

Figma prototype 2.0

Playtesters: Anonymous

Our second prototype created on Figma showcased the updated version of the hide-and-seek puzzle as well as the word decryption puzzle. We wanted to test how players interact with mini puzzles to solve a bigger puzzle. Additionally, we wanted to know whether our target audience would recognize the fairy tales we referenced in the puzzles.

What Went Well

- Easy to interact with the mini puzzles

- Once players understood that the images represented fairy tales, the tales were easily identifiable

- People understood how to navigate encryption puzzles, in general

- The encryption puzzle was enjoyable

What Didn’t Go Well

- Realized at the last minute that people needed something to write with for the decryption puzzle

- Players took more time trying to figure out how the puzzles interact with each other than actually solving it

- Thought that story hints were each their own puzzle instead of hints for the larger puzzle

- Players didn’t know that you can click on the text

Next Steps

- Need sufficiently more guidance and feedback

- Players are more encouraged to keep playing if they have hints to repeat over and over again

- Increase difficulty for college students

- Since our audience figured out the fairy tales pretty quickly, we wanted to make more layers to unlock those puzzles

- Make GUI more intuitive

- Making button design more obvious

- Onboarding user to click in the beginning with simple scene

- Note for next playtest to provide the player with writing utensils for the decryption puzzle (not required, but helpful!)

Figma prototype 3.0

Playtesters: Ji-Hong N., Natasha K., Stanford S.

Our final prototype created on Figma showcased the updated versions of the hide-and-seek puzzle, building puzzle, and word decryption puzzle. We wanted to test how long it took players to get past each puzzle. The building puzzle introduces a new mechanic as players are dragging pieces across the screen.

What Went Well

- Hints are more accessible

- Players were quickly accustomed to the navigation buttons with text

- Enjoyed the inclusion of sound/music, improved immersion

- Custom art is beautiful!

- Although the hide-and-seek puzzle was difficult, some found it satisfying after completing the three round

What Didn’t Go Well

- Players were confused on whether to wait for dialogue or click for dialogue

- Players took a very very long time trying to figure out the hide-and-seek puzzle

- Which is supposed to be our easiest puzzle

- Was not obvious that player had an inventory with usable objects

- Players didn’t understand the connection between spirits (same spirit growing older)

- Players were confused on whether to drag versus click to solve the puzzle

Next Steps

- Make objective more obvious by adding more hints

- Indicate to the player when they can use certain mechanics (click, drag, etc.)

- Allow player to replay essential dialogue for solving the puzzle

- Add Visual Indicators

- Show inventory at the top of the screen for every screen

- Smooth out timing of each scene

- Distinguish between automatic play of dialogue versus clicking

- Decided to keep the identities of the spirits more of a mystery to keep player intrigued

Our team derived inspiration from point-and-click escape room games like Gorogoa and Cube Escape. We wanted to maintain the same sense of mystery and abstract-ness by giving sparse hints and text. That being said, it was difficult to tell whether the puzzles in Heartwood were too difficult because of this design decision or just meant to be struggled with. Fortunately, most people enjoyed the puzzles but would have liked more guidance and feedback from the interface. Furthermore, our playtesters loved the atmosphere of the game, so I believe we can safely say that we were able to achieve immersion.

If we were to move forward with this game, our team would definitely move away from Figma and RenPy and more towards a platform like Unity. We realized that the functionality implementation of the puzzles produced a lot of errors in playtesting. We would like to work with a more feasible platform that allows players to save the state of the game and has a better GUI interface.

Playability

In our early design iterations, our team knew that we wanted to work within the point-and-click genre. Therefore, it is safe to say that the controls are quite easy to use as the player clicks through every stage of the game. That being said, our team put a lot of care into not overwhelming the player with too many decisions. Throughout the game, we created visual indicators for clickable objects including glowing drop shadows. Some buttons are activated at certain scenes while others are not to keep the player from making frivolous clicks. Lastly, in the onboarding of Heartwood, we guide the player to click on an object so that they get an idea about what clickable objects may look like.

With its focus on immersion and exploration, Heartwood could not have the usual hint system where a hint button simply gives the player a clue. Instead, we worked to guide the players just enough that they would eventually figure out the puzzle for themselves. This design decision may affect learnability because the people who naturally search the screen for clues may find our game more learnable. In addition, feedback from our Figma Prototype 3.0 indicated that we still needed to provide more guidance to the player about the objective of the puzzle. Our team ended up providing more dialogue from our characters to the player about a puzzle’s mechanics and objective. This was more in line with our vision of Heartwood, where puzzles take careful thought, players are invited to explore the space, and players must pay attention to the dialogue to figure out the puzzles.

Heartwood is a complete game with polished visuals and atmospheric music.The player is able to play through all of the puzzles and all visual assets are hand drawn by our team members Sammy Puckett and Krain Chen. Although we were not able to include custom sounds when you pick up or use certain objects, our team was able to find background music and puzzle-specific audio clips to help immerse the player into the forest.

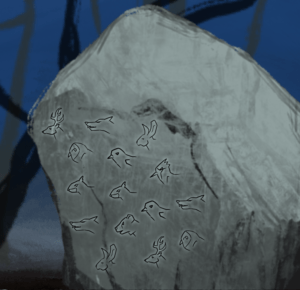

Narrative and Space

Our focus on immersion is intertwined with our natural setting. The bare, twisting trees of a forest in winter create ready associations of wonder and melancholy in the player and let them create their own visions of this fantasy world. The trees provide consistency for the entire space of the game (i.e. the “magic circle”), and the variation of landscapes within this consistent backdrop creates the sense of moving through a coherent space. The first-person perspective also directly relates the player to the protagonist, and the themes of change being alienating and reconnecting with childhood are broad enough for a wide range of players to connect with. In addition, details such as the line art for the puzzles, which are drawn with only short, straight strokes, make them seem believably etched onto rock or wood.

The trees provide consistency for the entire space of the game (i.e. the “magic circle”), and the variation of landscapes within this consistent backdrop creates the sense of moving through a coherent space. The first-person perspective also directly relates the player to the protagonist, and the themes of change being alienating and reconnecting with childhood are broad enough for a wide range of players to connect with. In addition, details such as the line art for the puzzles, which are drawn with only short, straight strokes, make them seem believably etched onto rock or wood.

To avoid breaking immersion, we did not use a traditional level system. But we took the concept of increasing difficulty and variety from levels to create all our puzzles. For example, the hide-and-seek puzzle becomes more difficult after each of the three rounds. The folktales puzzle, on the other hand, uses various ways of revealing the pictographs, such as clicking on an apple to reveal the Snow White etching or hearing the howls and clicking on the wolves to reveal the Little Red Riding Hood etching. This provides extra twists to the otherwise straightforward mechanics of fill-in-the-blanks and decrypt using substitution, and it also reinforces the themes in each folktale. Lastly, the final puzzle is a meta-puzzle, which ties together both the narrative themes of childhood and change and the physical pieces of the spyglass, which the Spirit had given the player as gifts for completing puzzles. It is our most difficult puzzle, and requires the player to have given thought to the narrative hints in the entire game, but it is also a satisfying culmination of the gameplay experience.

Final Playtest Feedback

Krain

Playtested game: Art Heist

Feedback:

+ Puzzles were a good level of difficulty, where none of them were so straight-forward that our team immediately solved it or so hard that we were truly stuck

+ The box was very cool — there’s something about having a locked box (especially an interesting looking one) that makes me want to open it, and the payoff of a really fun final puzzle inside was good

+ The combination of analog and digital was well-done (smooth transition)

+ The theme was consistent throughout the puzzles

– Hard to solve the crossword puzzle without prior knowledge of art history and it was unclear which questions we were allowed to Google and which we were not — maybe if there were a fact sheet (with helpful facts but also a lot of “useless” facts thrown in) so people did not have to Google answer at all

– Most of the puzzles were outside the box — having another puzzle inside the box would make opening the box even more satisfying

– The digital choose-your-own-adventure style ending felt abrupt and unsatisfying because no matter what choices we made on the phone, we would have won — so there was no real choice, and we may have been better off with a simple story ending+you won screen

Star

Playtested game: SpaceMail

Feedback:

+ Mouse and keyboard controls were so smooth (tidy Unity implementation)

+ Great take on “games in space” by showcasing galactic setting

+ Entertaining messages on the mail

+ Enjoyable gameplay due to variety of controls and mechanics

– Little bit difficult to be immersed in the third-person perspective

– Did not know the significance of the end dialogue until told by facilitator

– Subjectivity on what a “suspicious item” may seem unfair to the player

– Did not know the objective was to earn coins to bail out my family

John

Playtested Game: Escape From Your Mind

Feedback:

+ The maze puzzle is amazing! It is very interactive (players having to shift the box to lead the ball through the maze) and takes collaboration within the team (watching the map, communicating, then navigating the maze)

+ The clocks puzzle has lots of unique ways of approaching it and it was very interesting to think about

+ The progression of the puzzles do a very good job of building up enjoyability. The climax of the game is definitely the maze puzzle and the other puzzles do a great job of leading up to it

+ Overall theme is very intriguing compared to normal escape rooms

– The clock puzzle felt a little overwhelming at times with how many different ways you could approach the puzzle. Could use a little bit more guiding.

– The dial combination lock of the first puzzle felt very unintuitive to use as someone who has never used that kind of lock before.

– Could use a little more story to make the experience more immersive

Final Notes

We hope the player leaves the experience of completing Heartwood with some reflection on how their own childhoods, whether generally happy or as tumultuous as the protagonist’s, have shaped their current selves. We also hope that the interwoven poem and the imagery and music of the game will linger in their memory for a little while longer after their attention leaves the screen. However, we acknowledge that in the short period of time we had to create our game, we were unable to build for the visually or hearing impaired, due in part to the strong sensory components of our game. We would have loved to include alternative ways to experience this game, such as an auditory hint system for the visually impaired or a way to play the Little Red Riding Hood wolf puzzle while on mute, and given the chance to continue with our game, would build out those functionalities.

We were inspired by many games: point-and-click escape room games, especially Year Walk and Cube Escape, as we have already mentioned; but also In Requiem, for its incorporation of poetry as a key element in the game; and finally Monument Valley and Journey, for their gorgeous visual and audio components and themes that connect perfectly with the narrative. We cannot say our game is better, but we sought to combine the best elements of each of those games to create something that balanced the challenge of puzzles with the exploration of visual narrative that hopefully resonates with players.