Artist Statement

Do you like having a good argument with friends? Or have a real appreciation for making sure justice prevails? Introducing Court Case, a fun party game where you use your persuasive skills to prove someone guilty or innocent. Make your case using evidence given to you or go wild! Make up plot lines, proof, and argue against evidence presented by the other team. You may take respectful turns or interrupt and talk over each other. Be as formal or as chaotic as you want, because this game is all about having a good time with friends in a way that is enjoyable.

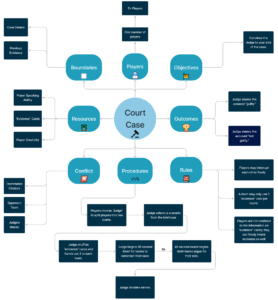

Concept Map

Initial Decisions for the Game

Players: We decided we wanted to make our a game a team-based game based on the parties present in a court room case such as the judge, the prosecution, and the defense. We wanted there to be a single judge who presides over and decides the outcomes of the cases to prevent gridlock over final decisions. Meanwhile, the prosecution and defense teams would have at least 2 players to create a need for teamwork as well as add to the chaos of overlapping voices in the game.

Outcome: The game is zero-sum, one side’s victory is the other’s loss. We wanted to keep things simple and approachable, rather than have the judge create complicated final sentences or compromises for the involved parties, they will simply choose which of the two sides made the better argument and award them the win.

Rules: Players were originally required to use all evidence that was presented by the judge, but could still make up evidence with their own imagination for use in the case. They would not be allowed to interrupt the opposing team’s speaking time and would have to wait for subsequent turns to counter their opponents’ claims.

Procedures: Players would draw their team affiliation from a deck; the judge would present the case and give the teams a minute to deliberate; then they would engage in 3 rounds where each team gets a minute to argue their case; the judge declares a winner after the final round. In our original procedure, we wanted to give the teams time to deliberate between rounds to allow them to prepare their cases and adjust accordingly to any new developments thus far. We also gave each team a minute per round to present their side of the case to keep things organized and give players equal time and space to speak. The judge would also play new “evidence” cards before subsequent rounds to give the two teams new information to adapt to and use in their arguments.

Boundaries: Players would be bound to work with evidence that had previously been brought up in the court, contradictions would be treated as “false evidence.”

Resources: Both “evidence” cards and the players’ own imaginations serve as resources for crafting arguments.

Objectives: Create a stronger case for your side of the dispute to convince the judge to rule in your favor.

Conflict: You will have to work together with your team and any arguments they present despite minimal preparation time. Also, your team has to counter the opposing team’s arguments and come up with a stronger, more robust case to avoid losing the game. Finally, you will also have to deduce and work around or appeal to the judge’s biases to improve your odds of winning.

Testing & Iteration History

To analyze our design choices and improve our game, we went through 7 rounds of playtesting in total and with each iteration, we went in wanting to test specific mechanics and validate them based on feedback from players. All our playtested versions of cards can be found in our appendix.

Playtest #1

Objective: During this initial playtest, our goals were to test several mechanics that we made based off of assumptions we had and also playing off the models of time-based challenge games like Pictionary and Charades. The specific questions we wanted to answer included:

- How in-depth do our cases need to be? What parts of the cases did players like the most and like the least?

- Was 1 minute an adequate duration for players to discuss and present their arguments to judges?

- Would evidence cards disrupt the teams’ plans and push them to be creative in crafting a narrative around this newly introduced information?

- How can we ensure that this is truly a social, party game where everyone participates?

Participants & Process:

For our first playtest that occurred in class, the participants were students who all knew each other but they did not really know anyone on our team. We had a total of four players, two on each side, and one of our team members acted as the judge/moderator. One member from our team acted as a notetaker as well.

For each playtest instance, we had the teams play a full case which includes 3 rounds of gameplay. After each playtest, we would ask the teams for feedback and pose questions related to the ones above to gain insight into how to improve without interjecting our own beliefs and biasing our progress.

Feedback: What Went Well…What Didn’t:

What Went Well:

One of the key aspects of our game is we wanted everyone to talk and everyone to participate in the game. In this playtest in particular, everyone was constantly talking with each other and we saw real, natural discussion arising from the case we posed to the teams.

Furthermore, players were being incredibly creative when it came to crafting their teams’ respective narratives to convince the judge. In this instance, one team found details within the case and chose the path of “the kids were not real and this was all a dream. The suspected killer is actually a loving dad who’s being framed.”

Most importantly, all players were talking, discussing, and sometimes laughing, which indicated to our team that we were onto making a party, social game but had to make adjustments. A counterargument to this observation we thought about is the fact that the playtesters seemed to be friends to some extent already, so we were not sure if, since they are friends, the playtesters were more talkative and social due to familiarity and not that our game induced this higher level of fellowship-type fun.

What Didn’t Go Well:

Primarily, the players felt that our case was too close to reality, too graphic, and very difficult to discuss. Players did not like the idea of discussing children dying or people in general being killed.

Moreover, players found that the case was biased. The defense felt that it was unfair that the case was written in a way that made the defendant already guilty.

Timing also became an issue, because the players stopped talking and discussing around the 45 second marker and allotting 1 minute left a 15 second gap of awkward silence where neither team had much left to say. To fill the space, players started just randomly throwing theories out and then retracting their statements.

Lastly, the players found that our evidence cards were not helpful and did not disrupt the conversation; they were either avoided entirely during the game play.

Changes We Made (only after hearing all feedback from playtesters)

- We immediately decided to decrease the allotted time players get to present their argument from 1 minute to 30 seconds.

- We also found that 4 players plus a judge might not be sufficient, and maybe more players

- All cases were changed to be more fantastical and light-hearted; we removed violence to avoid the overly realistic and possibly uncomfortable topic of death in a context that players might find triggering.

- The cases were also simplified in word count and content.

- All evidence cards became more concrete and case-specific in their content; all cases had their own evidence cards instead of a generic pile of evidence cards for all cases.

Playtest #2

Objectives: During this playtest, our primary questions were:

- How are the new cases perceived by the play testers? Are they more whimsical and light hearted?

- Do the new cases evoke more creativity, especially when we introduced evidence cards?

- Did all members of both teams speak and how did they interact with each other?

- How disruptive were the updated evidence cards?

- How did updated timing reflect in the user experience? Did it make the game more challenging, evoke more fellowship or hurt the experience?

Participants & Process

During the second playtest, we recruited four players and one of our team members as the judge/moderator (we were still ironing out the rules so we were not sure whether or not to allow a play tester to be the judge). We played a new, more fantastical case and more concrete evidence cards as well. For the latter part of this playtest, all members of our team had returned to observe the game as well.

Feedback: What Went Well…What Didn’t:

What Went Well:

The case’s content was more fun for the players and due to its lighthearted nature, the players were more creative with their narratives. Furthermore, the evidence cards provoked random tangents and disrupted teams’ arguments, pushing them to dive into realms of fantasy and magic to prove why their respective sides were right. One example would be: the case was about a missing stuffed animal; the brother of Alicia is the accused. The defense team came up with the idea of the brother having an identical twin who could have been the culprit after an evidence card was introduced saying “the brother is quiet today.”

Furthermore, we noticed that almost all players actively participated and were discussing back and forth, filling up the entire 30 second chunks they had.

Lastly, we noticed that the level of laughing, excited discussion, and overall smiles had gone up as teams tried to make up silly stories and addendums to their arguments to convince the judge of their argument.

What Didn’t Go Well:

One player was being marginalized in the discussion. However, when we observed this player’s behavior, we noticed that this player had expressed that they “did not care” or “were good with whatever their teammate wanted to say.” This led to us thinking about our ideal player profile and our target audience; it seemed that this game might not be tailored for people who are not as comfortable expressing opinions based on made up evidence and fantastical content. It also prompted us to investigate how to make this game more inclusive and see if this player’s behavior is representative of other people who would possibly play our game (we ended up finding that this player was a bit of an outlier).

Secondly, we received feedback that our evidence cards were too biased towards one side, making the other team feel like they were fighting an uphill battle. They suggested that we allow teams to have their own evidence cards and figure out how to use the ones they randomly drew at the beginning of the game.

Thirdly, we also noticed that players who were more confident or had backgrounds in debate were stronger in this game, being less apprehensive to state opinions and disagree with the opposing team. Members who lacked this type of background were more timid in their approach to expressing their opinion. *Note: These playtesters were not friends like in playtest 1, so we also think that because there was an absence of familiarity between the playtesters, they experienced a level of shyness or formality; they didn’t want to disagree or go toe-to-toe with a classmate they didn’t know well.

Lastly, the new timing was good in that it pushed players to think quickly and discuss, talking over each other and creating the crazy, social environment present in a party, for example. However, 30 seconds proved to be a bit too short and the judge had to keep interrupting the players to force them to stop at the 30 second mark.

Changes We Made (only after hearing all feedback from playtesters)

- We increased the time per round to 45 seconds to see if this might be more adequate than 30 seconds but still preventing the awkward silence of 1 minute from playtest #1

- We changed the evidence cards to be evenly distributed in terms of incriminating evidence for either side

- We tailored the target audience and player profile after seeing the dynamics from playtest 1 and 2, finding that this game might be best for extroverted people at a party and/or people who might already be familiar with each other or lack hesitation in confronting (kindly, of course) people they do not know as well.

Playtest #3

Objectives: During this playtest, our primary goal was to validate how to make players more creative and push everyone to participate. We entered this playtest during our weekly section with these primary goals:

- How does altering the evidence cards affect creativity and likelihood for players to ‘spin up’ new narratives?

- How does providing each team randomly drawn evidence cards affect discussion in comparison to the past playtests?

- How do more evenly balanced evidence cards influence which evidence gets introduced into the argument?

Participants & Process:

During the third playtest, we recruited four players and one of our team members as the judge/moderator (during section, it was tough to recruit more people, so we had to have one of our team members be the moderator).

Feedback: What Went Well…What Didn’t:

Firstly, one of the largest changes we made, per Khuyen’s great advice, was to try and limit the evidence cards to only contain single words such as “bird, trophy, dog sitter, etc” to see if that would spur creativity. We thought that with one word, instead of directing players and limiting their scope of imagination with hard evidence, they could use the word(s) as inspiration for their narratives and concocting their own proof.

What Went Well:

In this version of the game, the level of discussion was high and there was laughing and overall indicators of enjoyment. We kept the constant of using a whimsical, fantastical case, so the lightheartedness of the game seen in playtest #2 was also present here.

Timing-wise, the 45 seconds was definitely adequate and at some times, players would talk over the time. This suggested to us that time is necessary for the progress of the game, but that maybe we could open up this mechanic to “house rules” or allow game players to adjust this time limit to their liking, especially, since the goal of this game is to have fun and be social rather than be stringent on timing.

What Didn’t Go Well:

Although we thought that the one word evidence cards might incite creativity, they did for some players and for others, they indicated that they felt a level of exhaustion at having to continuously invent their argument with barely any concrete information about the case. For example, one player mentioned that because they had evidence cards like “trophy,” and “dog sitter,” they found it difficult to weave into their argument. Most importantly, players indicated that after a while, they felt silly arguing using these random words that felt irrelevant to the case.

Changes We Made (only after hearing all feedback from playtesters)

- We decided to do another round of playtests to further test the idea of “single world evidence cards” because we were not sure if the specific play testers we had just weren’t “feeling” the game or feeling creative at that time.

Playtest #4-6

Objectives: During these playtests, which are grouped since they took place in the same night with groups of different people, we tested the game in an actual party setting where students (over the age of 21) were drinking alcohol and playing our game. One of the key objectives for this night’s playtests was centered on which style of evidence cards we wanted to use: single-word cards or concrete evidence cards. We came in with these questions we wanted to answer:

- How do people in a party setting differ from people in our class playtests when it comes to disagreeing with the other team?

- How does the party setting affect the creativity and “flow” of the teams’ arguments?

- Which style of evidence cards renders the most social, creative user experience? This should include heightened laughter, discussion, back-and-forth disagreements, talking over each other a little, taking opponents’ arguments and manipulating them to work for their own position.

Participants & Process

During these playtests, we had 6 players per instance and a judge as another playtester. One of our team members acted as a shadow moderator in case any of the players had a question.

Feedback: What Went Well…What Didn’t:

What Went Well:

We found that players appreciated having evidence cards with more concrete information on them versus the singular word cards. Players indicated that they thought the more in-depth evidence gave them a starting point to create their creative narratives, rather than having to make up a whole story with the one-worded cards.

Furthermore, the 45 second marker seemed to be adequate for both teams to express their sides, and then we included an element of “house rules” so that when teams were not done completely explaining their side during a round, the judge just let them continue for another 15 seconds.

The teams also noted that the cases were funny and felt very “non-realistic,” and the content was helpful for them to feel like they were playing a game versus contemplating a realistic scenario.

In all instances of game play, all players were involved in discussion, going back and forth and deliberating within their teams. When asked how they felt about participating, the players mentioned that they all felt comfortable contributing and fighting for their side. This indicated to us that possibly this game is meant for people who are more familiar with each other, since all the players at the party knew each other (possibly strangers would not want to argue against each other).

Lastly, given that the players were eager to play and seemed to be in a “debate” or “competitive” mood, the whole game would last longer. Players would take longer to deliberate, longer to deliver their points, argue with the judge after the judge delivered their verdict etc. Feedback indicated that in this environment with friends drinking together, Court Case felt like a true party game rather than a manipulation of debate club.

What Didn’t Go Well:

In this specific playtest, the major things that didn’t go well centered around the variability of the type of players that were involved. These players are extroverted people who are known for being competitive. They pushed the boundaries of the rules of the game for the sake of fun (challenge and fellowship fun), and deeply interacted with the case and the other players. However, these playtests seem to be a bit of a departure from our class playtests, which seems to show that possibly this game is for a niche audience, specific type of person, or a specific type of setting.

Changes We Made (only after hearing all feedback from playtesters)

- Removed the idea of single-word evidence cards

- Added a bit more detail to the cases

- Added more ambiguity into the evidence cards so they weren’t as polarizing – they could be open to spinning for either side

- Increased the number of evidence cards in the deck so that we could replay a case multiple times with the same audience but have different arguments based on different evidence.

Playtest #7

Objectives: During this final playtest, we wanted to see how our new evidence cards, cases, and mechanics manifested. Our primary questions were as follows:

- How would teams interact with the randomly given evidence cards?

- Would all team members be involved in the game?

- Would people who were not as close or not friends be comfortable with crafting narratives and confronting the opposing sides’ viewpoint?

Participants & Process:

During this playtest, we had 6 players plus one of our team members as the judge while another team member was taking notes. The players were not all friends with each other and had relatively superficial familiarity with each other.

Feedback: What Went Well…What Didn’t:

What Went Well:

The teams indicated that the case was fun and lighthearted. They liked the idea of having evidence to base their arguments off of. Most, if not all, members of the teams interacted with the game and other players.

What Didn’t Go Well:

The game went quickly because players were not keen on pushing too far past the 30 second mark. Please note, we accidentally reverted to the 30-second model for each round instead of the 45-second model. We are not sure how to make the game last longer without complicating the mechanics further, and we were already at a later stage in the game design process (if given more time, we would return and investigate this issue).

The playtesters, when prompted about inclusivity in this game, suggested that we should include roles for the characters in the case i.e. the defendant and the accuser and allow for interviews by the teams of the characters. This way more people are actively involved in the progress of the game and would be speaking.

Creativity also faltered during this playtest; the players mentioned that they were not sure how creative they could be, if they could make things up, or if they had to stick to “reality” when devising their arguments. This meant that our rules were not clear and we did not communicate to them properly what they could do. One side even resigned from one round, because they simply didn’t have any evidence they wanted to present, which showed evidently that our rules were not well written; one does not even need to use evidence in any round and could make up whatever they would like to say, but it was clear the players did not know that.

Lastly, the lack of familiarity within the playtesters affected the discourse between them. In contrast with the playtests done at the party where everyone knew each other well, in this version, in class, there was a level of formality and respect for one’s peers that seems to conflict with the necessity of this game for players to be raunchy, loud, and somewhat contentious to win.

Changes We Made (only after hearing all feedback from playtesters)

- We reiterated in our rules that evidence cards are for inspiration and that players should be creative in creating their arguments

- We made the 45-second per round rule definite

- We changed our messaging to emphasize that this game is a social, party game for friends to try and combat the lack of familiarity issue we’ve seen numerous times.

Visual Design & Iteration:

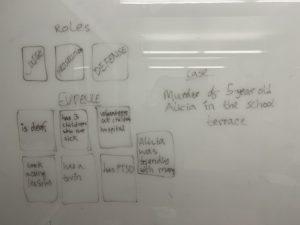

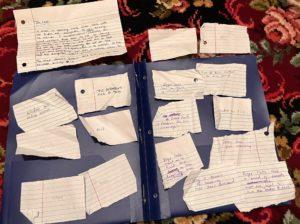

In our initial design phase, we aimed to map our the significant pieces of the game, including roles, cases, and evidence.

Above is our second phase of design for the game, sketched out with notebook paper. We did not pay too much attention to design principles at this game, because our aim was to test the game as fast as possible.

On our later iterations, which you can find on our Figma, we implemented class principles in effectively designing cards for a more intuitive player experience:

- Considered a player’s way in holding cards, which is why we made sure to place all pertinent information at the center of card

- At the corner of the card, we have the magnifying glass color coded to that players can easily see color affiliation when the cards are splayed, similar to how playing cards have the patterns in the corners.

- Created a color palette for each case with its corresponding evidence cards to make it easier for users to group cards together based on color

- We used the learning from lecture to not only rely on the rule book but also included instructions on rule cards

- Initially we had our case cards and evidence cards the same size and thought of having each scenario (which contains a case card and many evidence cards) in an envelope. Then we realized that envelopes are harder to manage for a social game, so we made the Case Cards significantly bigger so that in the box we can use them as dividers.

- Another reason for making the Case Card bigger so that it is visible to everyone during gameplay (using the idea of recognize instead of recall)

Accessibility:

We intentionally made the cards color-blind friendly since our cards are organized by colors. We stayed within a pastel color palette and avoided red-green color blindness triggers with the main gameplay cards. However, with the affiliation cards such as prosecutor and defense, although the cards are red and green, the colors do not play into either organization or an exchange of information. These cards include an image and a title to give context to what the cards mean; the colors red and green do not contribute to the user experience more than being purely for aesthetic reasons.

Final Rules

- Players select a “judge” for the game

- Judge divides rest of the players among Defense and Prosecutor teams

- Judge selects a scenario (a case card and all its evidence cards)

- Judge shuffles the evidence cards and hands out 3 random ones to each team

- Judge begins 30 second timer for players to construct their case

- Judge uses a timer to conduct the players to play three back-to-back rounds of 45 seconds each. Judge announces each time a new round starts.

- Judge reads out the case and then offers each group the chance to read it

- During each round players can use 1 or no evidence card. Players are free to make up evidence or argue against evidence provided by the other team.

- The judge finally decides which team won

Final Playtest Video

Our Prototype

For our game, we imagined that it would be packaged in an actual briefcase acting as the box or a box with a briefcase inside. On our Figma, one can see our prospective design for the packaging, keeping a minimal, realistic design to add to the “court house” theme and immerse players in the experience.

Print & Play

Print our game out and try it to see how fun it can be for your next party!