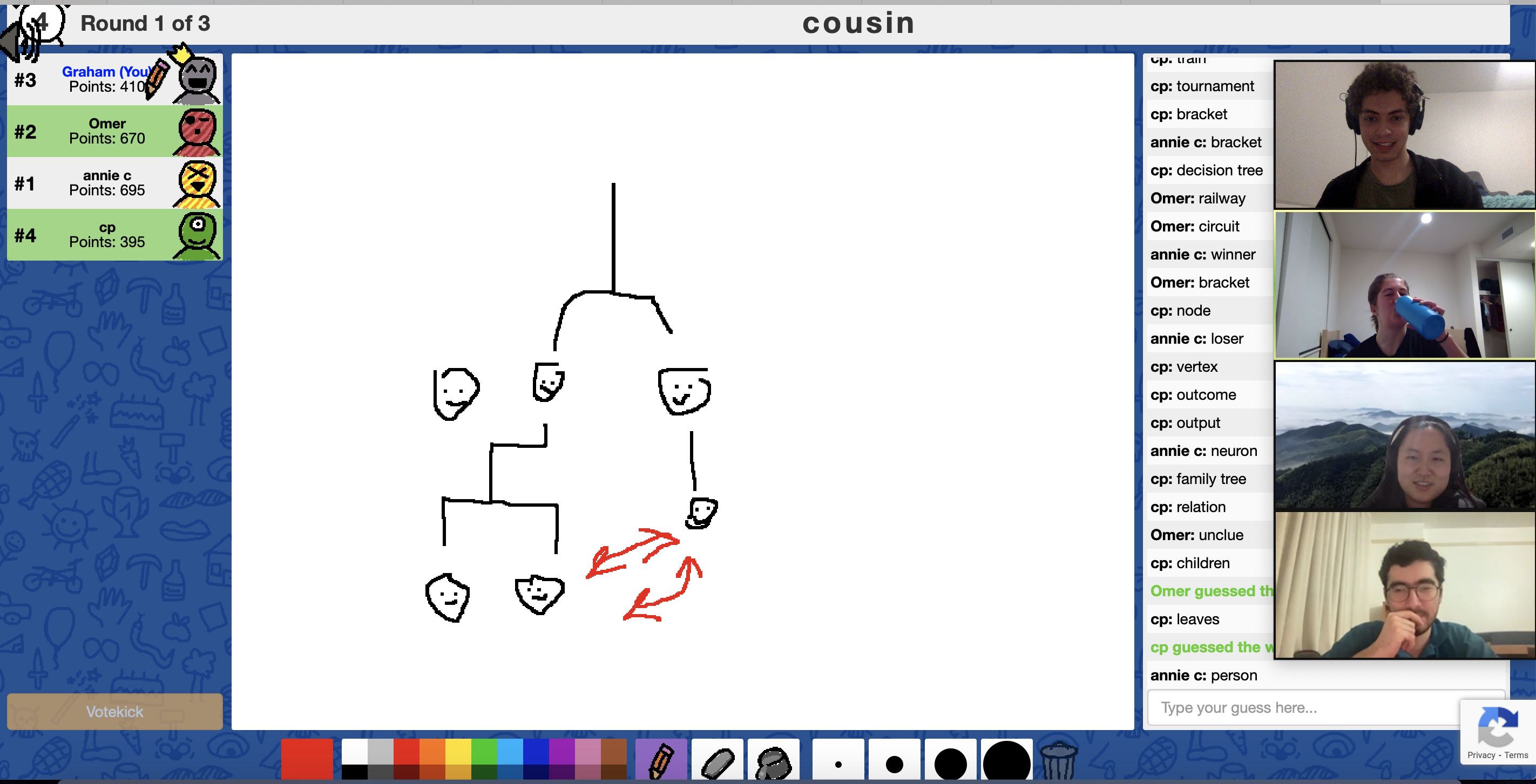

For this assignment, I played the online Pictionary-esque game “skribbl.io,” developed by “mel” a.k.a @ticedev on twitter. The game appears to be best suited for a group of friends who know each other (as opposed to a group of strangers), since that allows for in-jokes and other references to be deployed during the game, making things more fun and unique. In the game, players take turns being the drawer while everyone else plays guesser. The drawer slects a word from a pool of three options and then attempts to sketch out their word graphically. While this is going on, all of the guessers are simultaneously attempting to identify the drawing by posting into a public chat. When every one of the guessers correctly names the word or a timer reachers 0, the round ends and the next player becomes the drawer. Guessers earn points in a round based on the order in which they manage to guess the word (earlier = more points), while drawers earn points based on how quickly everyone managed to guess their word (incentivizing parseable drawings).

While skribbl.io is technically a multilaterally competitive game (after three turn cycles, only the person with the overall highest number of points “wins”), the point-earning procedure actually generates some interesting, almost altruistic behavior. You don’t get any points if you fail to guess the word, so in the absence of any other factors, the optimal thing for the drawer to do is to leave the canvas blank: that way, no one else gets any points! But by adding the ability for the drawer to earn points based on how well people can decipher their artistry, there’s a strong incentive not to fall into that degenerate case. It is the handling of this particular formal element (the procedures of point-earning) that allows skribbl.io to generate both the fun of expression (its primary type of fun) and, to a lesser extent, that of fellowship.

One way in which skribbl.io differs from other judging games is that the drawer is public — everyone knows who it is! This means that players can leverage what they know about each other psychologically to help out with the game (e.g. what kinds of movies does my friend like to reference?). Similarly, all of the guesses are made in public (even though this isn’t necessary given the online nature of the game) — this helps players struggling to decipher the drawing follow the logic of the other players and can stymie the frustration of being the only person in the group of guessers who hasn’t figured it out yet.

As far as my play session, I found the game fairly entertaining but not mind blowing. There weren’t really any epic failures, but at the same time the play session was fairly subdued. I attribute this partly to a problem my group and I noticed in our own game for P1. When it comes to fully online games, it can be difficult to type something and talk at the same time! This seems like a simple point, but it means that during a round the guessers are mostly silent, hammering away at their keyboards. This reduces the amount of fellowship fun that can be had, since a lot of that comes from the freeform interactions between players. That said, it’s a difficult problem to solve! One thing my group and I considered (but ultimately opted against) was some kind of speech-to-text automatic transcription, but that seems ill-suited for a game as fast-paced as skribbl.io. Instead, it might be worthwhile reconfiguring the game such that guessers shout out their guesses aloud and the drawer simply stops and identifies the winner when they hear the correct guess. This would mean that only the first guesser to identify the word could get points (in the original game, correct guesses are hidden from the rest of the chat), but the increase in dynamism could be worth the trade.