Inhuman Conditions is a game made by Tommy Maranges and Cory O’Brien (of Secret Hitler and Monster Prom’s fame, respectively). It originated as a board game, and has been translated to a web browser game. I played the browser version here. The game’s target audience does not seem to be very specific: according to its creator, the game was created for two players, but it “can be played on a quiet night in with a single friend, or at a bigger game night.” I think due to the extent of roleplaying that the game wants its players to do, it might be most suitable for players who are already comfortable around each other.

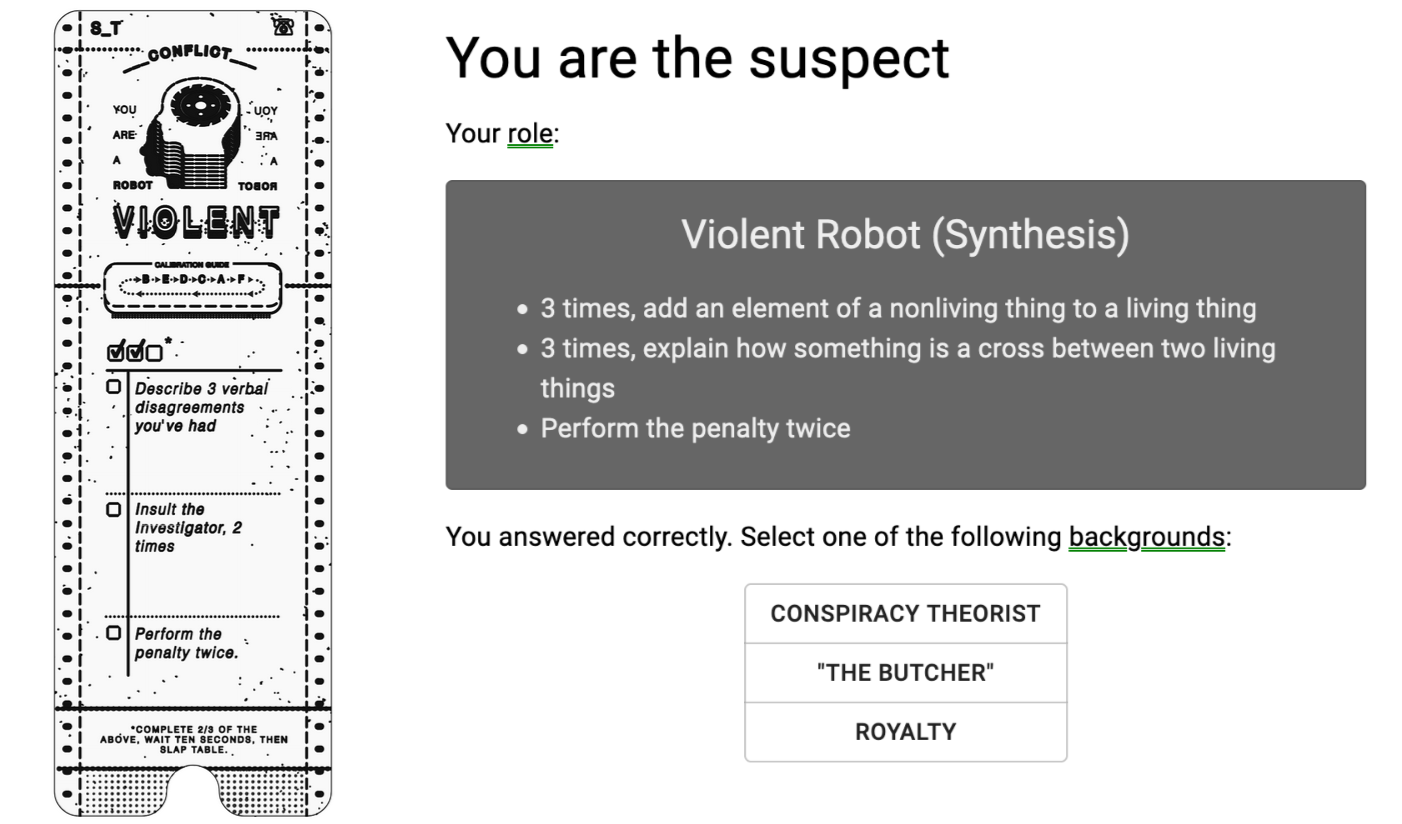

Some of the resources for the board game (left), and how they were displayed on the browser version (right).

Some of the resources for the board game (left), and how they were displayed on the browser version (right).

In fact, roleplaying scaffolds much of the fun of Inhuman Conditions. In this way, the game differentiates itself from other social deduction games such as Werewolf, which has more rigorous social rules (every night the werewolf chooses somebody to kill, the doctor chooses someone to protect, etc.). Such games progress based on the actions that players take, while in Inhuman Conditions, the actions are the discussion between the players. The game is for two players, but the creators noted that the boundaries of the game expand to spectators as well. Even though I only played the game with one other person, I think I would enjoy watching my friends play the game as well.

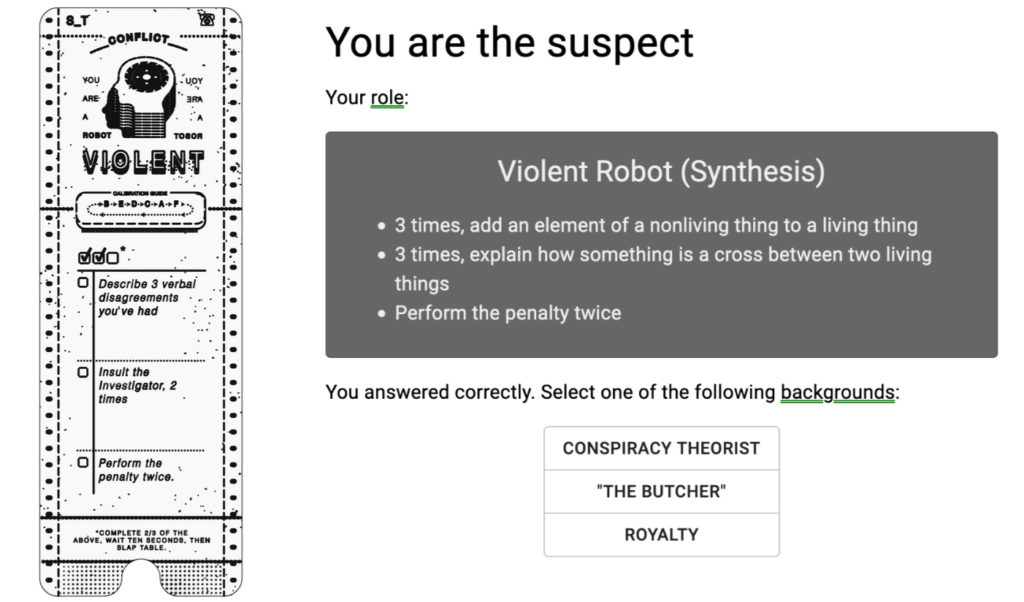

One notable element of the game is that the players can have different objectives, depending on the role they choose. The two players are either Interviewer or Suspect (chosen by consensus), and the Suspect is either a Human, a Patient Robot, or a Violent Robot (randomly determined). The Interviewer’s objective is to identify whether the Suspect is Human or Robot. A Human Suspect’s objective is to help the Interviewer recognize they are Human, while a Robot Suspect’s objective is to fool the Interviewer into thinking they are Human. So the game can be cooperative or competitive, depending on the role of the Suspect.

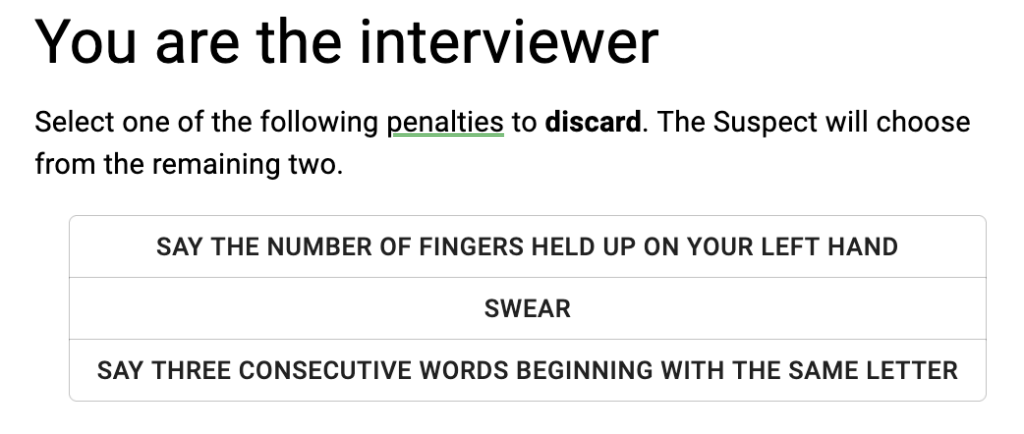

Players come to an agreement about playing as the Interviewer or the Suspect. They also agree on a penalty (a behavior Robot Suspects must do if they violate a rule, or if they want to win the game) together.

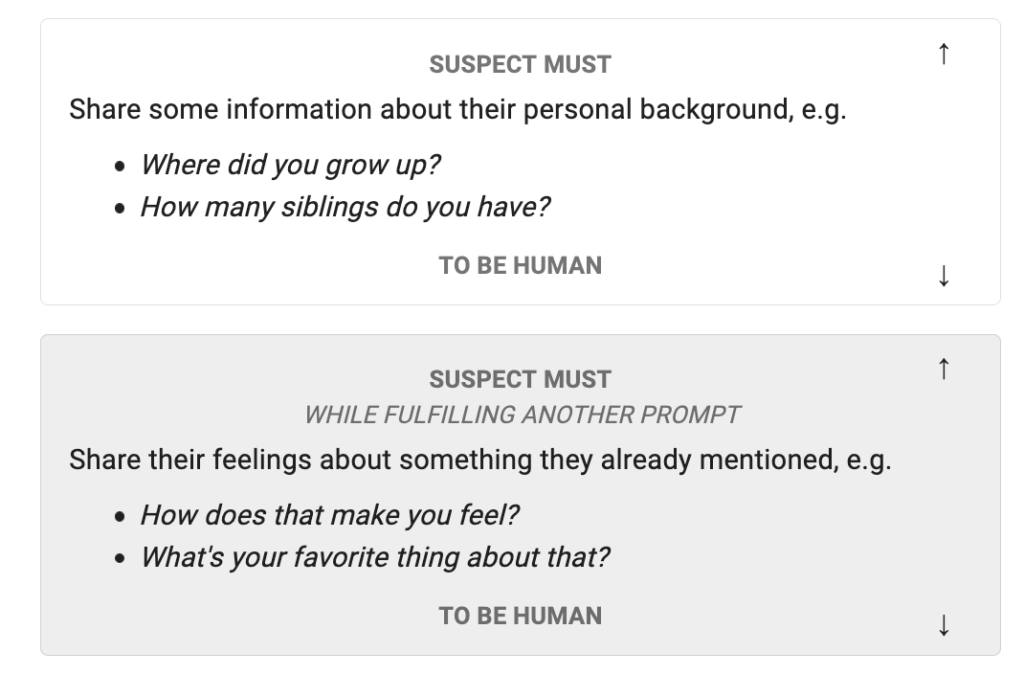

Suspects are randomly assigned to be Humans, Patient Robots, or Violent Robots. They can choose their own suspect background or get one randomly assigned to them.

Suspects are randomly assigned to be Humans, Patient Robots, or Violent Robots. They can choose their own suspect background or get one randomly assigned to them.

Another interesting element of the game is that despite the different objectives, the actions players can take are very similar between rounds. Only Robot Suspects have restrictions on their actions — they have to avoid a certain behavior (Patient Robots) or do a certain behavior (Violent Robots). These behaviors are intended to be “human-like” (for e.g., a Patient Robot can receive the rule to “not mention any people besides strangers or enemies.”), therefore, Humans can also exhibit these behaviors. For me, the fun of the game comes from navigating the make-believe social framework that exists within 1 round of the game. (I would classify Inhuman Conditions as a game of fellowship and fantasy, in LeBlanc’s terms).

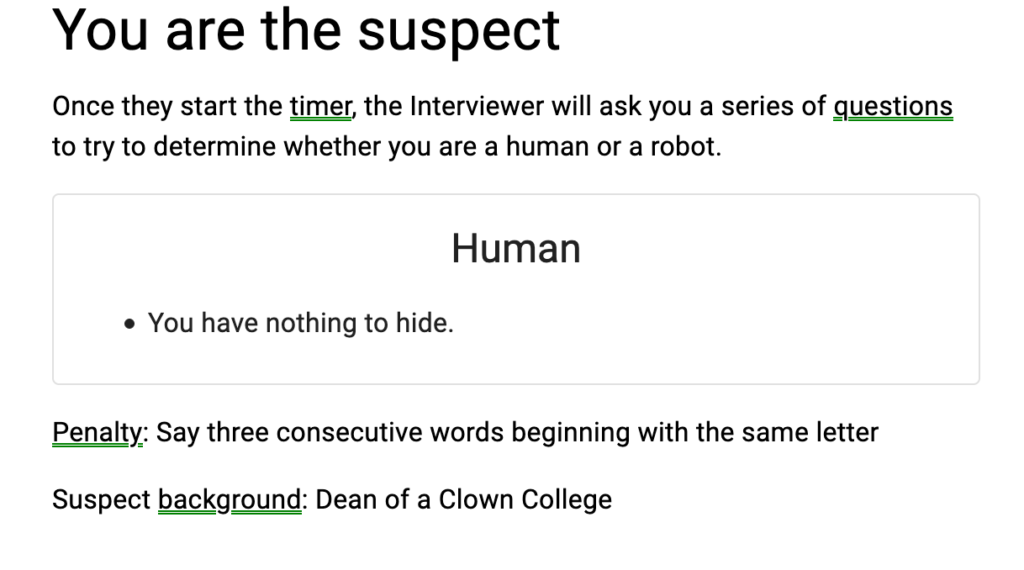

We played 5 rounds of Inhuman Conditions, and I really enjoyed the game. I particularly liked the roleplaying aspect of the game, and — while I’m usually a self-conscious person — I think the set-up and story of the game really helped me get into character. The short time frame for each round (5 minutes) also reduced the pressure to develop a consistent character. I found myself roleplaying even when I was a Human Suspect and did not have any restriction on my behavior (for one round, I was Dr. R, the dean of a clown school, whose answers to the question “what kind of problems would you solve a ladder?” consists of “put it in a nursery for kids to play on.”). I also very much enjoyed engaging with the characters the other player came up with — for example, diving into the tragic childhood of my friend’s character of a renowned professor. (TW: death.)

My friend (Suspect): “I had 12 siblings.”

Me (Interviewer): “Had?”

My friend (Suspect): “I used to have 15.”

Me (Interviewer): “How did your mother feel about that?” (this was a preset question from the package)

My friend (Suspect): “She died giving birth to the 5th child.”

(at which point I could have pushed about who the mother of his other siblings was, but I didn’t have enough time.)

Some moments of failures include having to read the really long rules right when we were excited about jumping into the game. The rules were also somewhat confusing because they interweave story and mechanics (for example, the rule specifies that at the end of the game, an undetected Robot has to shake the Interviewer’s hand awkwardly, a detail that is more story than mechanics). Even though I think this was done to establish roleplaying as a key factor of the game, it made the game more boring upfront. I also did not particularly enjoy some of the penalties, as they were difficult to blend into a normal conversation and would have easily blown a Robot’s cover.

Example of some of the penalties that can be chosen in the game. Some of them are more easily incorporated in normal conversation than others (planning for 3 consecutive words beginning with the same letter, while conversing about the life of a make-up character, is quite challenging!)

Overall, I thought Inhuman Conditions was a really enjoyable social game that focuses on the fun of roleplaying (rather than just psychological social deduction). I would make the game better by making it easier for Robots to incorporate penalties into the interview conversation, either by balancing the difficulty between penalties, and/or add more help for Robots to come up with ways to incorporate penalties. Currently, Robots might face penalties that would very easily reveal them as Robots if they have to carry out the penalties. For example, Robots can be given a preview of some questions that Interviewer might choose to ask from the packet, so they can prepare.

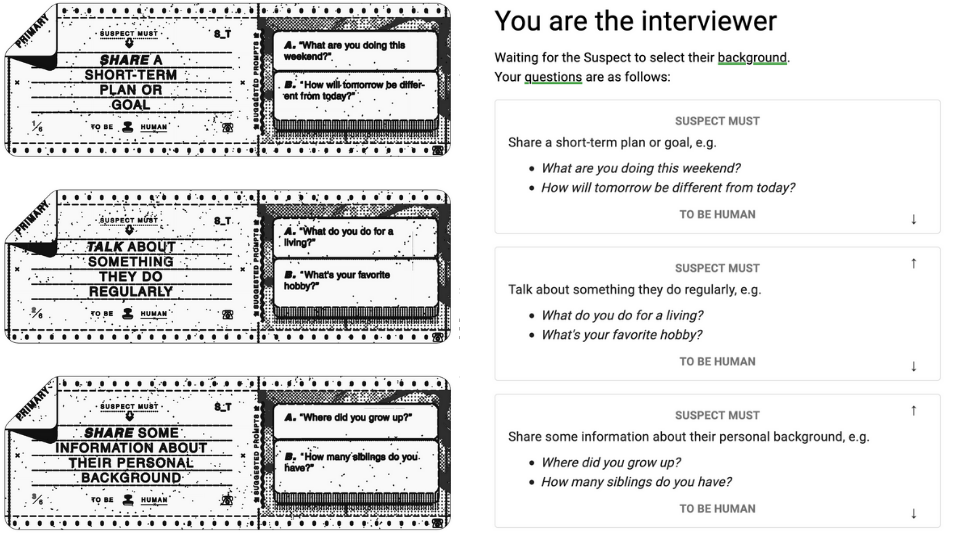

Examples of questions that the Interviewer sees. Robot Suspects can be shown 1 of these cards, or a sample of the “example” questions from different cards.

I would also want the game to be more challenging for Human Suspects. As of now, a Human Suspect does not have to think much about their actions in the interview phase (the only strategy would to not accidentally perform the penalty, and this is almost impossible for some of the penalties). Perhaps the backgrounds written for Suspect could be more detailed, and only the Human Suspect knows these details. The Interviewer can also be provided with some of the Suspect’s background details or a more general version of that detail. These background details could be written in a way that forces the Human Suspect to avoid certain behaviors (for example, “you dislike your sister, so you never talk about her”). This way, the Human Suspect has to be careful to not contradict what the Interviewer knows about them and be mistaken for a Robot.