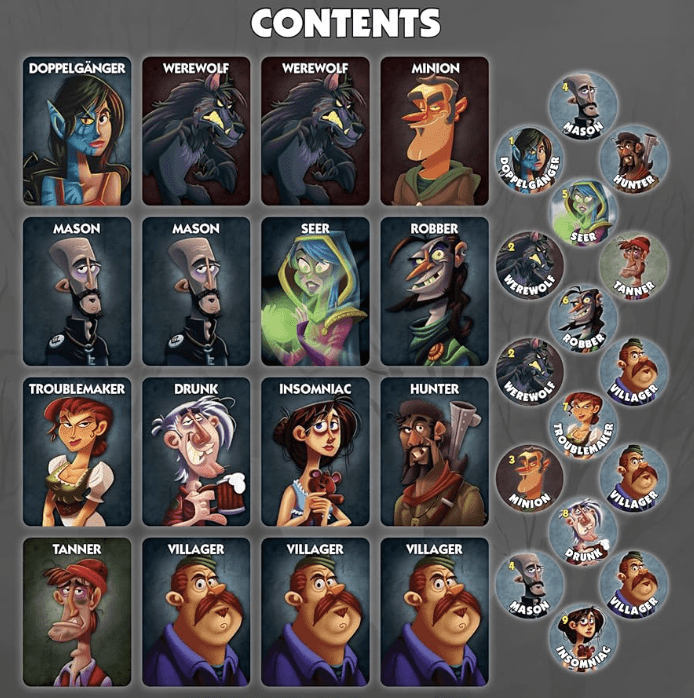

The game I chose for this competitive analysis is Werewolves, originally designed by Dmitry Davidoff and later adapted into commercial versions by various publishers, including Bézier Games (Ultimate Werewolf). I played the analog version of the game with a group of 8 players, using a printed role deck and basic tokens to represent night actions. Werewolves is designed for social gatherings and party contexts, often played by middle or high schoolers, college students, and adults in informal settings. The core appeal is its reliance on conversation, reading others, and bluffing.

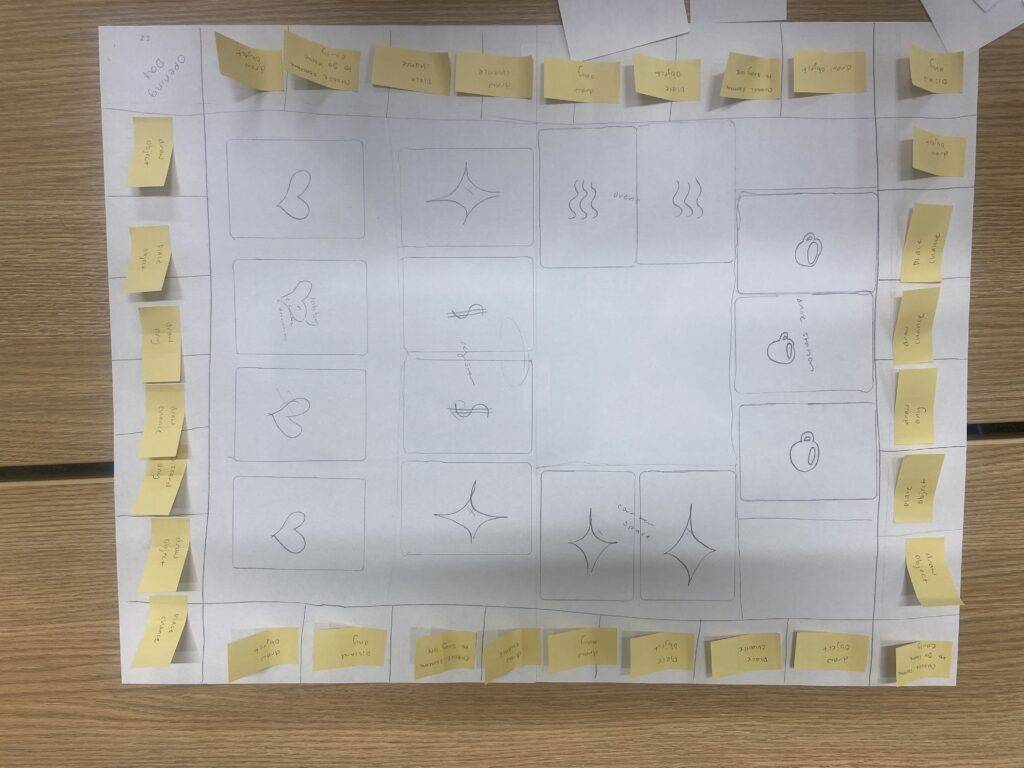

Both Werewolves and our board game center around hidden roles and deception, but they differ significantly in how they integrate strategy, movement, and individual incentives. The main distinction is that Werewolves is purely social – with no board, cards, or physical objective -whereas our game blends deception with tactical movement, card draws, and role-specific goals. In Werewolves, the suspense lies in discussion and deduction. Every round, villagers must figure out who among them is lying while werewolves try to avoid suspicion. It’s an emotionally intense game that thrives on human behavior and group psychology. Our game, in contrast, adds structured mechanics (like object cards, dice rolling, and chance cards) that create layers of strategy beyond just conversation. These formal mechanics give players other ways to influence the outcome – particularly for those who might not feel as confident engaging in open verbal deception.

One of Werewolves’ greatest strengths is how cleanly it executes its core mechanic: hidden roles and group suspicion (3:05). There are no dice, movement mechanics, or tokens beyond role identifiers. Everything flows from the dynamic between players. This results in fast-paced rounds where group psychology becomes the game itself. Watching a werewolf smoothly lie their way out of suspicion while villagers turn on one another is a testament to how powerful player-driven gameplay can be.

However, Werewolves also has notable drawbacks. Once a player is eliminated, they’re out for the rest of the game. Especially in larger groups, this leads to boredom and disengagement. Our team’s game avoids this issue by keeping all players active until the “opening day” event, even if someone is suspected of being a saboteur. This ongoing participation improves player retention and encourages a longer-term strategy. Another downside is the reliance on players being outspoken and persuasive. In quieter groups, Werewolves often falls flat. Our game mitigates this by offering more structured, tangible ways to take action – through cards, object placement, and dice movement. While this sacrifices some of the raw social tension that makes Werewolves exciting, it opens up opportunities for strategic deception outside of verbal argument. We could push this further by incorporating mechanics requiring or rewarding suspicion, such as mandatory accusations or voting intervals – something Werewolves excels at.

Compared to other games in the social deduction genre like The Resistance or Secret Hitler, Werewolves is defined by its simplicity and emphasis on large group play. It strips away external mechanics and puts full weight on interpersonal interaction. While our game draws inspiration from this approach, it aligns more closely with titles like Betrayal at House on the Hill or Dead of Winter, where board movement and item interactions play a key role alongside hidden motives.

What truly differentiates our game could be its dual-layered win condition. Players aim to help their team succeed (employees vs. saboteurs) and pursue personal role goals that allow them to earn points regardless of the overall outcome. Werewolves lacks this nuance – once you’re out, you’re done, and if your team loses, there’s no consolation. Adding these personal incentives opens the door for more complex motivations, alliances, and betrayals. A saboteur might let the store rating rise if it means completing their individual mission, creating gray areas that make the game more psychologically rich.

The core ethical question Werewolves raises is this: is it okay to deceive people if everyone consents to the game? And what happens when deception goes too far? Werewolves made me reflect on how deeply games can mirror real social anxieties – being falsely accused, excluded, or navigating power dynamics. It reminded me how hard it can be to speak up when everyone’s against you and how convincing someone to turn on a friend can feel thrilling and cruel.

This has important implications for our own game design. We want to keep the deception fun and lighthearted – not hurtful or alienating. That means building in safety valves, like cooldown turns, anonymous accusations, or optional disclosure mechanics to reduce pressure. It also means designing for trust recovery. If a player is falsely accused or suspected, they should have meaningful ways to regain credibility. Games like Werewolves often end relationships mid-game; ours should leave room for redemption.

Using the MDA framework, Werewolves thrives on emergent dynamics – player conversations, suspicion spirals, and group votes – all shaped by its ultra-simple mechanisms (night/day cycle, elimination, hidden roles). The resulting aesthetics include tension, triumph, fear, and betrayal. Our game, while more complex, aims for a similar aesthetic. However, our mechanics – object cards, role objectives, dice-based movement – are more robust and layered. We need to ensure these don’t drown out the central emotional beats of a social deception game. Every mechanic should reinforce tension, mystery, or misdirection. If something doesn’t support that, it may need to be rebalanced or removed.

One design opportunity we’ve discussed is how the object placement mechanic could be used as a form of covert sabotage. What if particular objects subtly shift the store rating up or down? What if their effects are only revealed later? This would preserve the emotional highs of deception but tie them closer to our board’s interactive components.

During our playtest of Werewolves, one decisive moment came when a quiet player, who had been ignored all game, suddenly revealed they were the Seer and accused the final werewolf. The werewolf panicked, over-defended, and was voted out. It showed how timing and trust are everything in this genre. That moment has stuck with me, and I hope we can emulate it with key mechanics in our game – moments of sudden clarity or chaos driven by well-timed reveals and reversals.