Exercises from Ch. 1 of Games, Design, and Play

1. Identify the basic elements in a game of your choice (actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, players).

Game of choice: Animal Crossing: New Horizons (ACNH).

- Actions: ACNH has a boatload of actions the player can take, including but not limited to: fishing, catching bugs, planting flowers/trees/bushes/shrubs/money, collecting artwork, watering plants, talking/giving gifts to villagers, collecting/building furniture, and terraforming your island.

- Goals: Although the explicit goal of the game is to make it attractive enough to invite the beloved K.K. Slider (the best AC character) to give a concert on your island (after this the credits roll), the game is incredibly open-ended and offers many different goals to different kinds of players within Bartle’s taxonomy of players. Socializers can improve their relationships with the villagers on their islands, becoming best friends with each of them and earning their posters as pieces of furniture for their homes. Explorers can continue taking expeditions to different islands, searching for the perfect villager or fruit to add to their island. Achievers can collect all the fish, insects, plants, and furniture they can, improving their island to achieve the coveted 5-star rating. The only players that are left out are the killers, but I’ve never met a killer that plays Animal Crossing. Maybe they just spend the whole day hitting their villagers over the head with their net (Fig. 2)?

- Rules: Although ACNH prides itself on the freedom it gives its players, the developers had to give the game some structure to allow players to truly flourish. The most fundamental rule of Animal Crossing is that the world exists on a very strict grid (Fig. 3). This means that plants, furniture, rocks, holes, items, trees – anything in the game – must be situated neatly on top of the grid. Despite there being some wiggle room to this rule (e.g. angled rivers/cliffs, rounded edges on paths), these exceptions still sit nicely within the grid of the world and do not disrupt it. Within this grid, players are allowed to design residential neighborhoods, shopping districts, orchards, or anything else they can dream of provided it sits nicely within the grid. However, despite this rule, many players have devised clever ways to angle certain furniture to give the illusion of a less “regular” space between grid squares. Other rules include not being able to improve relationships with villagers more than once or twice per day, not scaring away fish/insects by running past, and the limits on terraforming on sand.

- Objects: Of course, the highlight of Animal Crossing‘s objects is the furniture. There are an endless number of furniture sets, colors, and combinations the player can make that achieve both the explicit goal of the game as well as the Achiever’s implicit goal. Along with furniture, players have access to tools (e.g. fishing rods, nets) to catch fish/insects, collect wood/gold, and glide effortlessly over rivers. Additionally, as evil as this may sound, one could analyze the villagers themselves as objects in ACNH – especially for the Socializer.

- Playspace: The playspace is your island! However, as mentioned previously, there are even more islands besides yours to explore…

- Players: Players are (typically) the “Resident Representative” that makes all the decisions across the island, including enacting ordinances, building public works projects, and preparing the island to celebrate various holidays. This gives players an enormous amount of agency over the other villagers, but is also highly dependent on each player’s desires within the game. If a player wishes to be “just another villager,” never enacting ordinances and allowing the island to grow and expand (mostly) on its own, they’re allowed to do that!

2. As a thought experiment, swap one element between two games: a single rule, one action, the goal, or the playspace. For example, what if you applied the playspace of chess to basketball? Imagine how the play experience would change based on this swap.

To contrast two cozy games, let’s take a look at Animal Crossing: New Horizons and another game that exploded in popularity during the COVID pandemic – Stardew Valley. Both are considered by many to be the best of the best in cozy, farming simulator-type game design. However, Stardew Valley has an important social element to its gameplay that Animal Crossing does not: the ability to have explicitly romantic relationship with the other people living in your town. Animal Crossing, to my knowledge, has never allowed the player to “date” other villagers, including hints at romance between other villagers with nothing made explicit. In Stardew Valley, however, there are multiple mechanics that create an entire romance system, which has become a main selling point of the game for many (Fig. 4).

Villagers in Animal Crossing have simple dialogue lines that often repeat if prompted too often, and many have predictable and nearly interchangeable interactions with the player. Villagers of the same type will tend to greet you similarly, have near identical interests, and have predictable likes and dislikes. This allows for the developers to spend more time designing more villagers, each with slightly different outfits and styles that all fit cohesively within their villager type, allowing for the absurdly high number of 413 unique villagers in the game. By contrast, Stardew Valley has only 60 non-player characters. This is because the developer took the time to write out distinct personalities and storylines for each individual character, thinking deeply about how they would react to a litany of different scenarios given their characterization. In Stardew Valley, the NPCs are characters – for many, Animal Crossing villagers are (unfortunately) just moving pieces of furniture. Including stronger characterization and more thought-out writing in Animal Crossing would undoubtedly reduce the number of unique villagers there are to customize the player’s island. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as Stardew Valley is an incredibly fun and successful game despite its lower NPC count. However, since the player base of Animal Crossing is already conditioned to playing the game without very involved dialogue/extensive relationships with the villagers, it would not only alienate younger players that don’t understand how to navigate complex interpersonal dynamics (such as starting an accidental polycule) but also reduce the number of options for a player to express themselves through their villager choices.

3. Pick a simple game you played as a child. Try to map out its space of possibility, taking into account the goals, actions, objects, rules, and playspace as the parameters inside of which you played the game. The map might be a visual flowchart or a drawing trying to show the space of possibility on a single screen or a moment in the game.

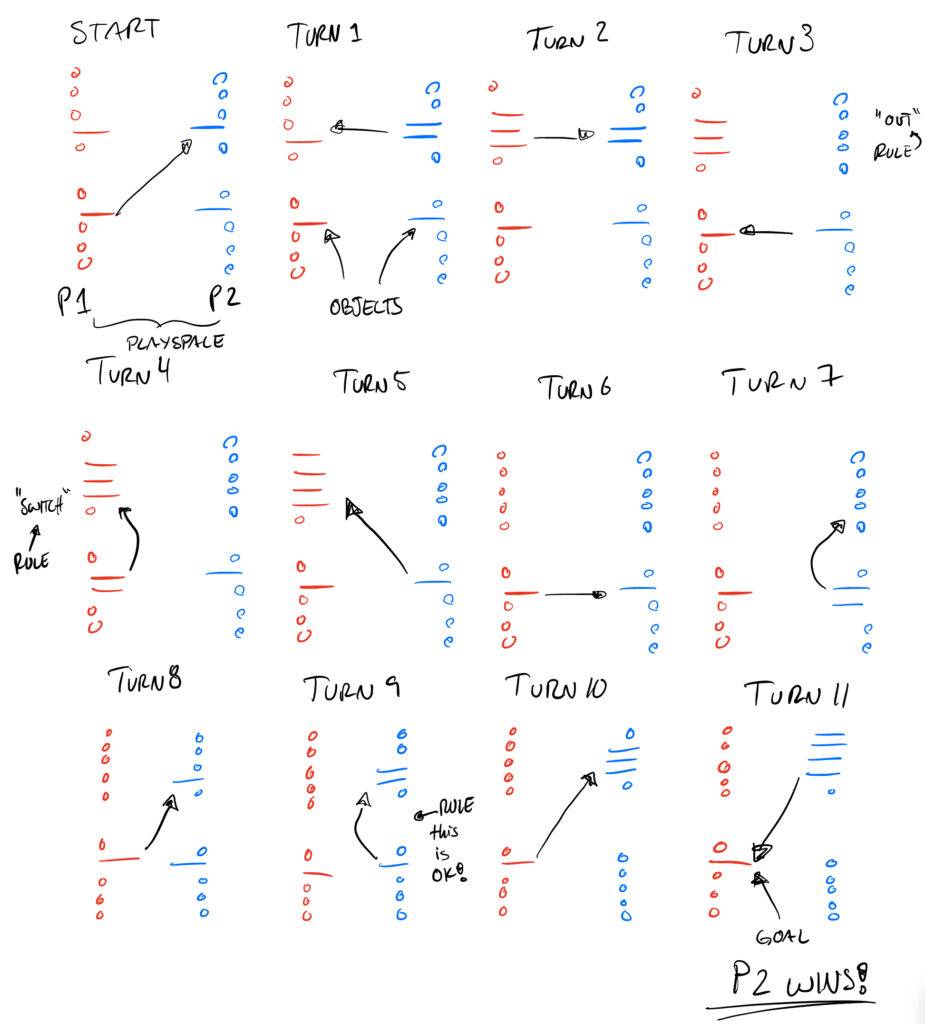

My favorite game as a child was Sticks. It was my favorite because you can play it almost anywhere and I always win! Two players start with one finger pointing out on both hands. Players take turns “hitting” one of the opponent’s hands with one of theirs, summing the fingers on the player’s hand to the fingers on the opponent’s hand. Players are allowed to forfeit a “hit” for a “switch,” where they move some fingers from one hand to another (note: it MUST be a unique switch, e.g. 2-3 -> 2-3 is not allowed). Once an opponent’s hand reaches five fingers, it’s considered “out.” Out hands cannot be hit, BUT a player can switch to bring an out hand back. Play continues until one player is out on both hands.

4. Pick a real-time game and a turn-based game. Observe people playing each. Make a log of all the game states for each game. After you have created the game state logs, review them to see how they show the game’s space of possibility and how the basic elements interact.

Finally, I’d like to cover a card game. Specifically, the most evil (and my favorite) card game Blackjack. The game is simple – just sum to 21! But don’t forget that the house always wins (I always play the dealer). A typical game of Blackjack begins with each player being dealt two cards face up, and the dealer being dealt one card face up and the other face down (Fig. 6). Then, starting with the player on the left of the dealer, players either “hit” (take a card) or “stay” (pass their turn), trying to get their cards to sum to 21. If a hand sums over 21, they automatically lose. However, if a player stays when they are under 21 and the dealer gets closer to 21, they lose. Additionally, if the dealer gets exactly 21, all players lose (unless one already has 21). After watching me beat my roommate, I’ve observed the following regarding its possibility space:

- Although the possibility space of the game is quite narrow (player below 21 & below dealer, below 21 & above dealer, at 21, at 21 with dealer, above 21), its probability space is quite broad, especially when you shuffle together multiple decks. Simple strategies have been devised to allow players better odds on average against the house (~48%), but this is only when these strategies are played to perfection and do not take into account more social dealers (such as yours truly, occasionally).

- The objects of the game are the cards and chips. The chips certainly influence the player to engage in more or less risky behavior depending on how much they’re willing to lose, and add another stressor to the game on top of the simple sum to 21.

- The goal in any game is ostensibly to win, but in reality is to earn money by betting.

- Players can act in bad faith. Obviously on a casino floor a dealer won’t be encouraging you to hit on a 19 while showing a 6, but I’m not on a casino floor. I enjoy Blackjack for the social engineering role the dealer (and other players) have when encouraging or discouraging another player to hit.

- Rules and actions are simple and straightforward. Who could lose at this game? All a player can really do is draw or pass. I know you’re at 20, but I can promise you as the dealer that the Ace is next.

Image Creds: