By Yutong, Ginelle, Xueqi, and Niam

- Play our game!

- Artist’s Statement

- Design Vision & Target Audience

- Formal Elements & Game Mechanics

- Formal Elements

- Game Architecture

- Types of Fun

- Onboarding

- Game Scope + Big Picture Vision

- Current Slice

- Full Game Implementation Plan

- Accessibility and Ethics

- Full Game Narrative Plan

- Design and Process

- System Model

- Design Choices

- Narrative-Relevant Clues

- Clue-Dependent Dialogue

- Integrating Images into Clues

- Minigames

- Tone Construction

- Development Process

- Iteration History

- Iteration + Playtest 1 & 2 (5/6 and 5/8)

- Iteration + Playtest 3 & 4 (5/13 & 5/15)

- Iteration + Playtest 5 & 6 (5/20 & 5/22)

- Iteration + Playtest 7 & 8 (5/27 & 5/29)

- Iteration + Playtest 9 (6/3)

- Final Playtest (6/6)

- Acknowledgements

Play our game!

https://xueqi-chen.itch.io/ernest-estate

Artist’s Statement

Ernest’s Estate is a mystery-driven embedded narrative game where players unravel an inheritance conspiracy on a rural farm. Set in the aftermath of Ernest Harrow’s mysterious death, players take on the role of a young lawyer brought to settle his estate, but quickly find themselves piecing together family secrets and betrayal.

Inspired by courtroom narrative games like Ace Attorney, narrative exploration games like Gone Home, and deduction and logic games like 221B Baker Street, our aim was to create a game that bridges story, logic, and discovery. By day, players investigate the Harrow farm — exploring barns, woods, and family homes. By night, they stand in a courtroom, presenting their findings to determine who deserves the land. At the end of the game, there comes a twist in the narrative: Ernest never died at all. He orchestrated it all to uncover the truth.

Our game’s core aesthetic is discovery of lies, of love, and of legacy. Each clue is important, each character hides something, and each courtroom verdict influences the ending. This project is a slice – a single day of the five-day mystery arc – and we designed it to demonstrate our complete vision, mechanics, and tone.

While the gameplay focuses on exploration and deduction, the narrative tone of Ernest’s Estate is more layered and emotionally charged. Beneath the surface of a vibrant countryside lies a world filled with ghostly presences, buried truths, and shifting family dynamics. The tone blends the bittersweet and the uncanny, conveying a sense of mystery not just through plot twists, but through emotional ambiguity, dramatic irony, and the feeling that something is always just out of reach. With the protagonist’s unique ability to speak with the dead, the game evokes a transcendent, almost illusory atmosphere where memories, secrets, and betrayals blur the lines between right and wrong. We want players to feel not just the thrill of solving a case, but the weight of unraveling legacies, and questioning whether justice ever has one clear answer.

(Moodboard visuals)

Design Vision & Target Audience

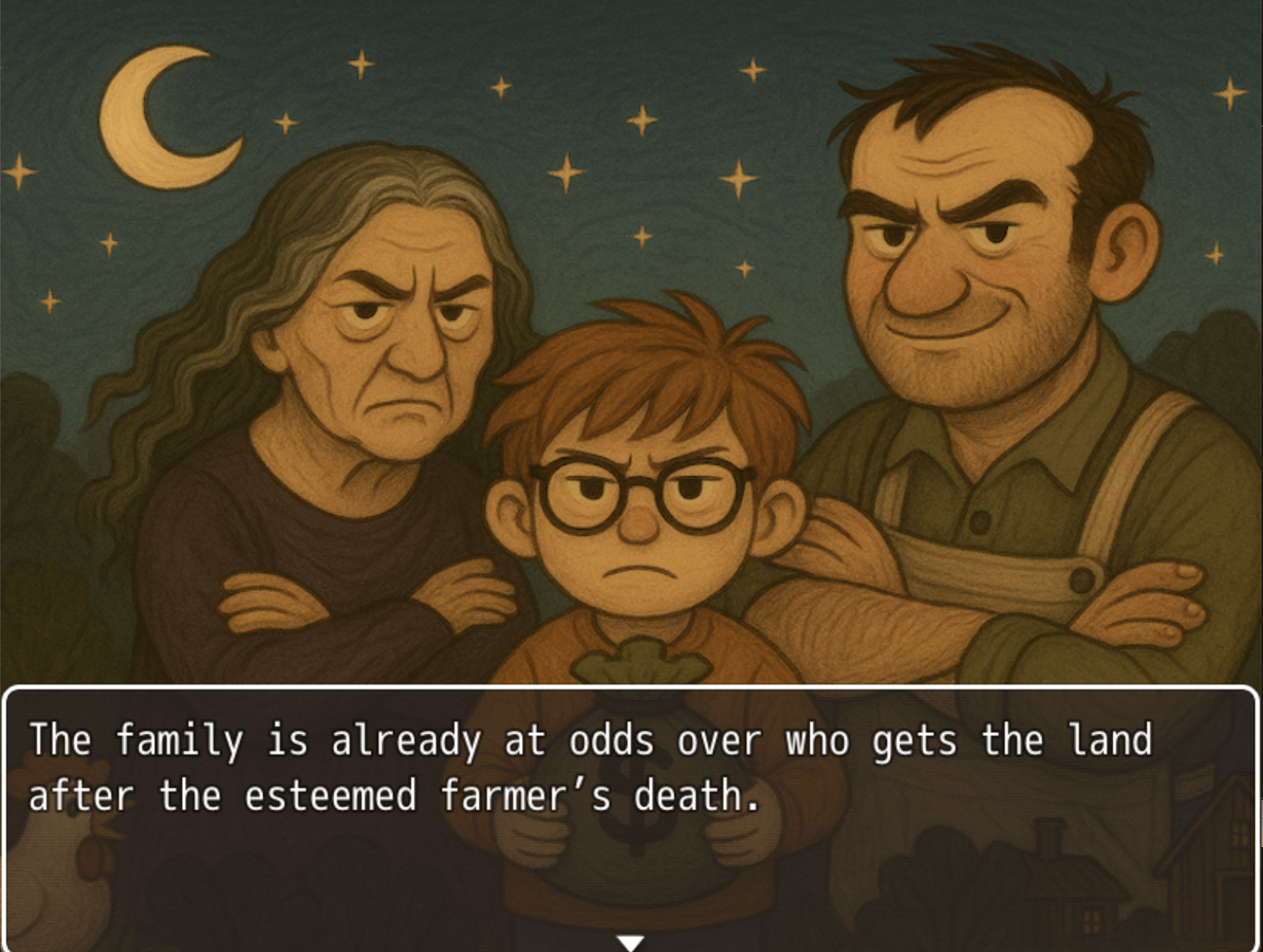

Our primary audience is adult and college-aged players who enjoy games centered around observational problem solving. These are players who may have less time and want to play a shorter game, but are interested in a more patient, story-driven experience. In terms of player types, we designed primarily for Explorers and Achievers in Bartle’s taxonomy. Explorers enjoy the layered environments, subtle clues, and inter-character relationships that they figure out through exploring the game. Achievers enjoy the courtroom sequences, which are a culmination of the logic and clues, and there are tangible effects on the narrative. We also imagine our main audience as teens and adults who are okay taking their time and thinking through what’s going on. The game doesn’t rush you. You can go at your own pace, explore every room, talk to every character, and make your own decisions based on what you believe really happened.

Here are some of the main design values we focused on:

- Discovery Through Exploration: We want players to feel like detectives, not because the game tells them what to do, but because they figure it out themselves. You learn the truth by noticing small details, remembering what characters said, and connecting the dots.

- Peaceful Gameplay with Real Consequences: We wanted players to be able to take their time and think through what is happening. The game doesn’t rush you, and there is no timer. You can go at your own pace, explore every room, talk to every character, and make your own decisions based on what you believe really happened. Ultimately, you can choose when to submit your evidence to the judge, and as long as you’ve reach a baseline quota of collecting a few clues, the evidence has real narrative consequences on the story.

- Story and Gameplay Working Together: Everything in the game connects to the story. You explore, talk, and find clues during the day, then go to court at night. The puzzles in the gameplay have direct relevance to the story. It is not like an escape room, where the puzzles might be word or number-based with no direct relevance to the narrative, but these are all intertwined, pulling the player into the narrative.

- Real Emotions: This game isn’t just about solving a mystery – it’s about dealing with inheritance, family, and legacy. Every character has their own reasons for acting the way they do. We wanted players to feel like these are real people, not just characters in a game. To this end, we have crafted complex narratives and created, to the best of our ability, realistic interactions with individual characters.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Formal Elements & Game Mechanics

Formal Elements

- Players: Ernest’s Estate is a single-player digital game. The player takes on the role of a young lawyer sent to manage a family’s farm estate after the mysterious death of its owner. As the player explores the farm and interacts with different family members, they begin to uncover a conspiracy hidden beneath the surface. However, in the playtests, we have found that individuals enjoyed playing in groups of two, being able to go back and forth about what the clues might mean.

- Objectives: The player’s main objective is to investigate the truth behind each family member’s involvement in the mystery. Each in-game day focuses on uncovering one person’s motives and secrets. By collecting clues and making decisions, the player builds a case and presents it in court each evening to determine whether that person should be jailed, disinherited, or set free.

- Outcomes: Outcomes change based on the player’s choices. In the courtroom, players can “win” by successfully proving someone’s guilt, “partially succeed” by proving a character guilty enough to not inherit the farm but not guilty enough to go to jail, or “fail” and accidentally let the wrong person inherit part of the farm. These outcomes affect the ending, when Ernest comes back, as well as the overall feel.

- Procedures: Players can move through the environment using arrow keys and interact with objects or characters using the space bar. When interacting with family members, sometimes players can choose between different dialogue options. These conversations branch depending on which clues the player has found, and in some cases, certain clues must be found before new dialogues are unlocked. At the end of each day, players enter a courtroom scene where they present evidence in the order they choose, based on what they’ve discovered. These interactions form the core game loop, shown below:

- Rules: We prevent players from traveling outside the boundaries of the computer screen or going in buildings/interacting with objects that are not meant to be interacted with. Some objects and characters can only be investigated after specific conditions are met, such as finding a related clue or speaking to another character. During the courtroom phase, only the clues the player has discovered can be used. A player needs to submit a certain set of clues in order to achieve the outcome.

- Resources: The game’s most important resource is information. Players gather clues through objects and conversations, and those clues become critical pieces of evidence in court. Dialogues are also part of the resource system, telling players where to gather clues next and unlocking new clues to be accessible.

- Conflict: The main conflict is social and emotional (as opposed to physical). The player who to accuse and how to think about incomplete information. Characters also have conflicts with each other, which play out through branching conversations and keeping secrets. Each person jailed has connections to other individuals, which are the focus of the next day’s investigation.

- Boundaries: All gameplay occurs within the computer screen. The slice we’ve built represents one full in-game day, and all interactions – exploration, dialogue, and court – take place within that digital space.

- Values: This game emphasizes values of truth, legacy, justice, and empathy. It asks players to pay attention not just to what characters say, but how they say it, and to understand motivations and regrets.

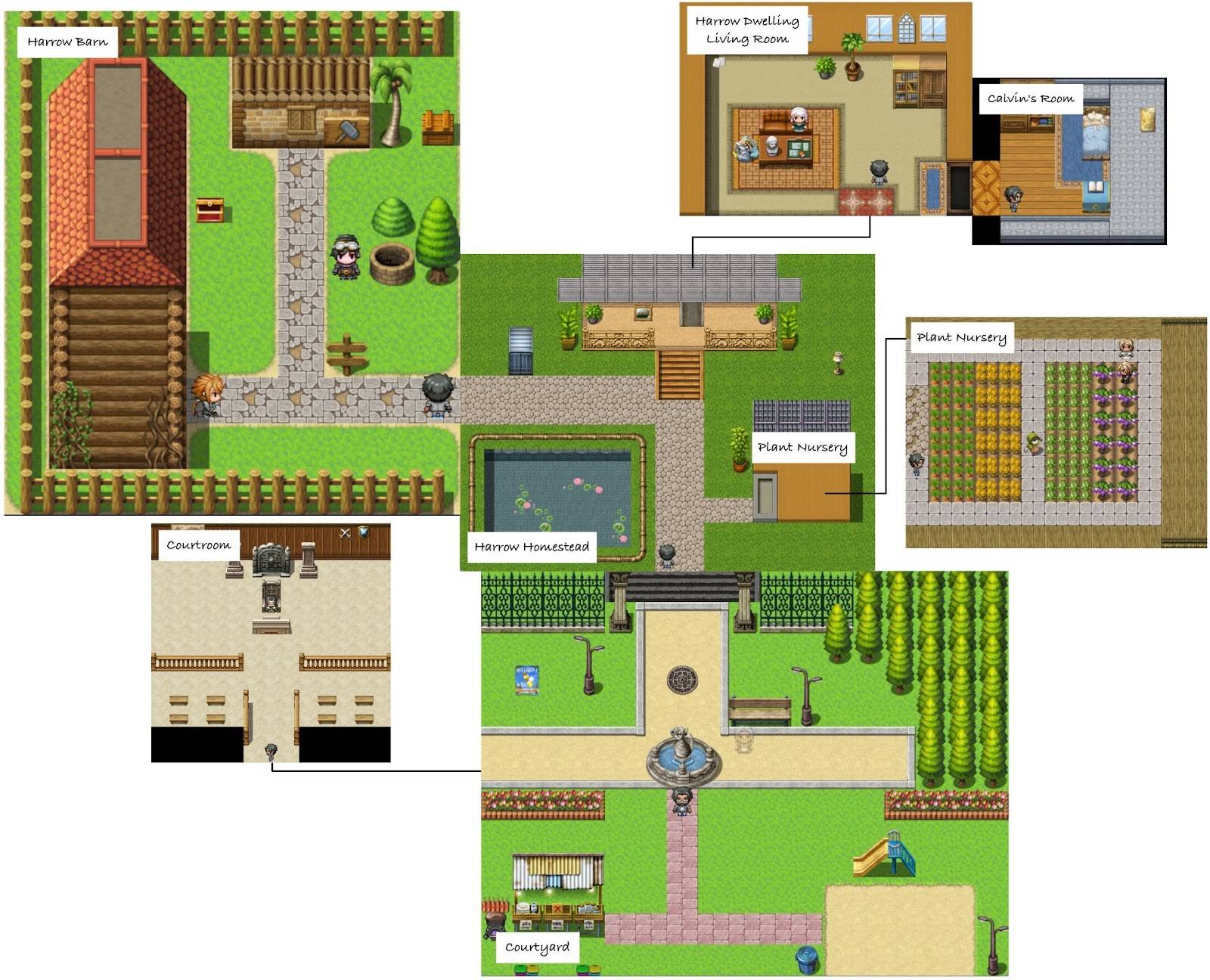

Game Architecture

The game takes place on the Harrow family farm, split into six key locations: the porch, living room, Calvin’s bedroom, the barn, the orchard, and the community square. Each space is carefully designed to feel like a real farm, with realistic objects, layout, and atmosphere. Characters move between rooms, walking from one space to another, simulating the feeling of roaming around a physical space and investigating, as the clues are physically hidden or placed in these spaces. The courtroom is always accessible, and the player can choose to present their evidence whenever they feel ready.

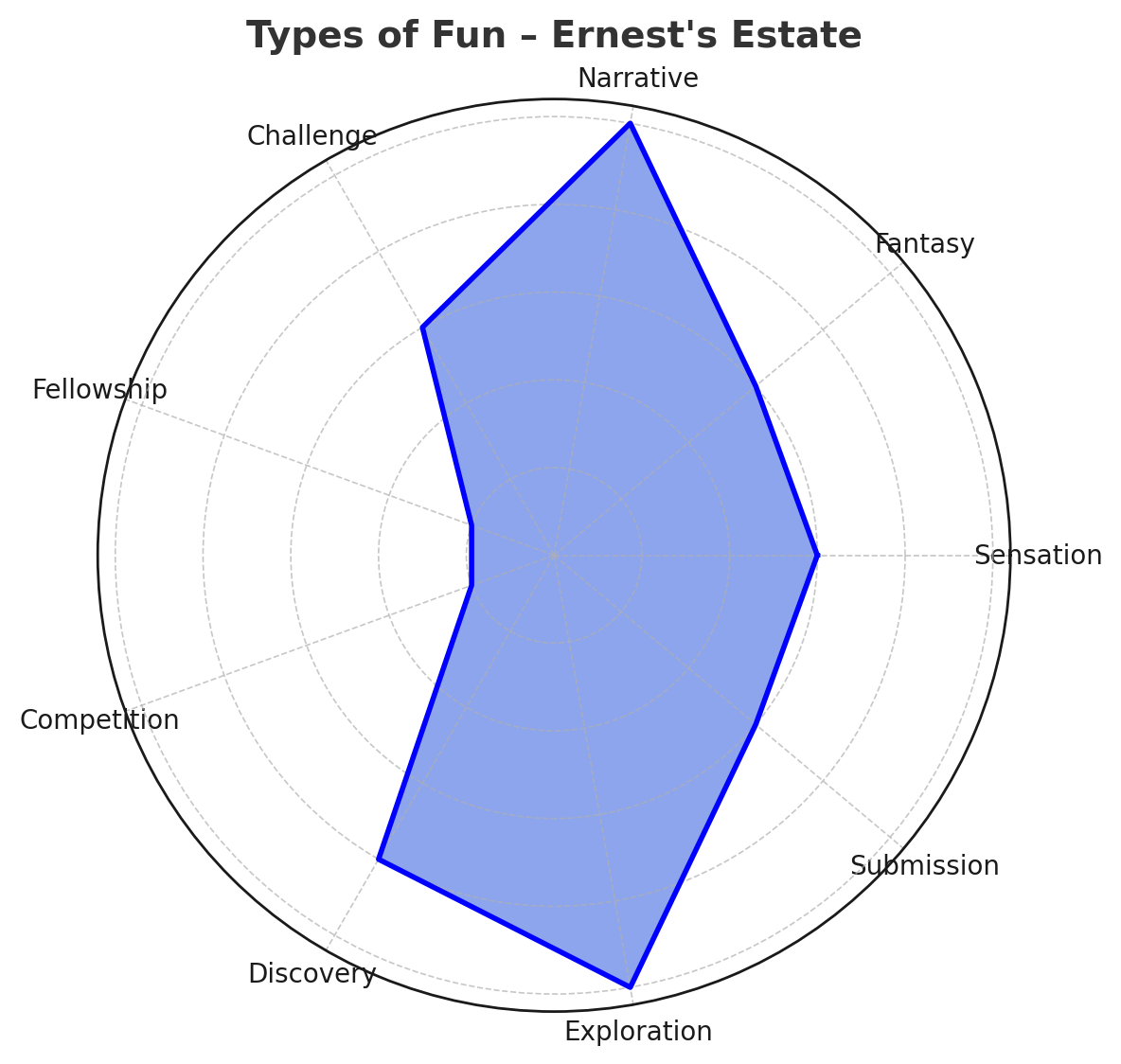

Types of Fun

The core types of fun in Ernest’s Estate are narrative and exploration, delivered through the mystery-driven experience where players slowly piece together what happened. The narrative is woven into every space, object, and interaction, with characters acting suspicious and responding to different questions alongside clues being relevant items to the space and narrative. The gameplay relies on the player to want to explore and to enjoy exploring. They move through the six different spaces searching for clues and interacting with the characters. Discovery is another key component, with players feeling the satisfaction of moving forward through the visual feedback of unlocking and finding clues that push the narrative forward.

We also focus on including some moderate level of challenge both through the courtroom system – having to make a claim and prove what the player says – and through the gameplay itself, with hard-to-find, unclear, or conflicting clues that need to be pieced together. The minigame also increases the challenge of this game. However, right now, most of the clues are relatively easily visible and there is only one minigame, so we foresee the level of challenge going up in a full implementation of the game.

There is also some component of sensation, through the aesthetics and background music. We also tried to design the characters and dialogues to mimic the mysterious, eerie feeling we wanted the player to have while they played. While this is a foundation, we see room to enhance this through feedback sounds when interacting with items and more variety in background music, among other things in a larger implementation of the game.

Other aesthetics like fantasy, discovery, and abnegation are slightly present. Players experience fantasy by stepping into this new story of lies, secrets, and betrayal. The slower pacing also supports players who enjoy narrative games that let them think, observe, and process at their own speed, allowing for a relaxing abnegation-like experience.

Onboarding

Our onboarding process is designed to feel like a natural part of the story rather than a separate tutorial. We use active learning techniques, letting players discover how the game works on their own through exploration. The game begins with a short narrative setup with a few sentences and images, starting with the dramatic “Ernest is dead.” It then puts the player into the game, but with none of the clues interactable yet. Lucy, the ghost, is in the courtyard with ‘…’ over her head. She introduces the player to more context, telling them about the family and giving them their first objective: go meet everyone and report back. This encourages players to explore the space and meet the characters without pressure. No clues are interactable yet, so players can’t accidentally skip ahead. Once they’ve talked to everyone, Lucy gives them a concrete objective: figure out what’s going on with Calvin. This moment marks the beginning of “Day 1.”

We also provide some embedded hints for onboarding, including an instruction board inside the courtyard, right next to where the player spawns and something that is accessible throughout the game, which explains basic movement (arrow keys) and interaction (space bar). We also made the player’s current objective always visible in the top-right corner of the screen.

We designed this onboarding with tips from George Fan’s 2012 GDC talk in mind, focusing on:

- Start with something fun – The onboarding story is told dramatically, introducing the player to the game in a fun way. And the rest of the ‘onboarding’ is through interactions with the characters and a ghost, keeping the tutorial interesting and not feeling like a tutorial at all.

- Make the player do what you want them to learn – Players are asked to talk to everyone, encouraging interaction and exploration implicitly rather than being told they must explore in order to learn information.

- Use characters to teach – Lucy acts like a guide, delivering narrative and onboarding at the same time. The other character interactions have suspicious and ominous warnings in them, making the player ready to investigate by the end of the ‘tutorial.’

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Game Scope + Big Picture Vision

Current Slice

Ernest’s Estate is a vertical slice of a bigger mystery game. This means we built one full in-game day that shows what the rest of the game will be like. In this slice, players explore the farm, talk to characters, find clues, and then go to court to make their case. This explore-investigate-accuse loop is the heart of the full game, and we wanted to make sure it worked well from start to finish.

We created six rooms on the farm: the porch, barn, stalls, living room, Calvin’s bedroom, and the community square. And the seventh room is the courtroom, next to the community square. Each space has items to look at, clues to find, and characters who say different things depending on what you’ve already discovered. Some clues only show up after talking to certain people, which makes players think about the order they explore and who they trust. This system will keep growing in the full game, but all the locations will stay the same.

At the start, players meet a ghost named Lucy who introduces the story and teaches you what to do. She tells you to talk to everyone and come back to her. This is our way of teaching players how to move around and interact with the world through the story itself. This is exactly what the onboarding would look like in the full version of the game

The courtroom at the end of the day is where the player uses what they’ve learned. You pick clues to present and try to prove who did something wrong. If you pick the right clues, that person goes to jail. If your argument is weak, they still get part of the inheritance. In the full game, the court cases will look the exact same and the format will be the same, but we plan to make the challenges and evidence harder to piece together as the player learns how to work with the game and gets more involved in the narrative of the story.

We chose to build this one day fully instead of rushing to make the whole game. This is because, quite honestly, a mystery game that just gave away the secret would be a little boring. We thought it would be much more interesting and complete to finish everything from the writing to the sound to the UI to feel finished and work together for a single mystery. All of these would be individually developed day-by-day for the full game according to the full game implementation plan below.

This slice ends with a real decision and real consequences. It shows exactly how the full game will feel: five days of uncovering secrets, deciding who to trust, and delivering justice.

Full Game Implementation Plan

If we had more time, we would have expanded the game into a full five-day mystery game, with each day focusing on a different character and a new part of the story. We would keep building on the systems we’ve already created, but make them more complex as the game went on.

One of our main goals would be to make the clues more challenging. Right now, players mostly find clues by exploring and talking to people. In the full game, clues would be harder to piece together, sometimes contradicting each other or coming from characters who lie. Players would need to figure out not just what happened, but who’s telling the truth and why.

We would also grow the relationships between characters. Right now, Calvin only has a suspicious relationship with Odette, and only 3 of the players give relevant, plot-moving clues, but in the full version, they would react to each other too, may move around more, and form more complex relationships.

To keep the gameplay interesting, we would also add more minigames, such as finding an object in a crowded room, piecing together ripped pieces of paper, matching handwriting samples, etc. We had the time to implement one, but would love to implement more.

Sound would also be a bigger part of the experience. Right now, we have background music, but in the full game we’d want to add sound effects for different clues, rooms, minigames, and people. This would help the narrative feel more real and immersive.

We also have other technical improvements planned, such as characters having “…” above their heads when they had something new or important to say. We would also add more hidden clues and increase the total number of clues, so players could miss a few and still build a strong case.

Accessibility and Ethics

With more time and a complete game, there are a ton of accessibility features we would love to include.

Some features that we already included and thought about are:

- No Time Pressure – The unlimited time to find clues and interact with characters allows an individual who may need more time to navigate to play the game just as easily as others who may navigate it quickly.

- Text-Based Dialogue – In addition to pictures, there is always a text-based caption of what was shown in the picture, allowing those with screen readers to easily play the game. In the future, we would love to add a voice-based option as well to interact with the game while preserving the way the narrative feels.

- Constant Access to Past Clues and Current Objective – Allowing a player to always go back and see these things reduces the need for them to retain all this information mentally, allowing the gameplay to be easier for younger players or those who may struggle with this.

- Simple Keyboard-Only Controls – Players can navigate the entire screen through arrow keys and a spacebar, with no need for complex key combinations or more technical equipment necessary.

With more time and a complete game, we would love to add adjustable text size, colorblind-friendly design, and a voice-based interaction option.

The largest change to the game I would like to make is including more of a range of personalities and backgrounds in the characters. This is especially true for the main lawyer character, to allow the player to customize their character look and feel. We tried to implement this, but unfortunately just couldn’t figure it out technically in time. This would be the single biggest and most important change we would like to implement.

Full Game Narrative Plan

In the full version, the mystery around the farm builds over the course of five days, with each player having their own dark secret.

Day 1 – Onboarding + Calvin’s Deception (implemented)

The player discovers that Calvin, the supposed heir to the farm, purposely never signed the farm permits. His plan was to let the farm go bankrupt so he could sell it to Capstone Industries and turn it into a factory. The player gathers enough clues to prove his intentional betrayal in court, and Calvin is arrested. Throughout this process, the player learns that Odette is the one who facilitated that relationship between Capstone and Calvin. Thus, the second day objective is about uncovering the true relationship between Capstone and Odette.

Day 2 – Odette’s Scheme

On Day 2, the player learns that Odette first started working with Capstone to cheat her way into winning jam competitions by bribing the judges because she’s secretly struggling with money. As part of this process, the player sees that Mae, Ernest’s sister, is one of the judges helping her win. The third day’s objective will be to prove that Mae is taking bribes.

Day 3 – Mae’s Bribes

On this day, the player collects evidence for Mae’s bribe-taking, as well as uncovers who those bribes are coming from. While they piece together her backstory, they also see that Mae is also taking bribes from Dorian. The fourth day’s objective becomes to figure out what Dorian is hiding.

Day 4 – Dorian’s Hidden Past

The fourth day, the player uncovers Dorian’s biggest secret: she isn’t who she says she is. The player finds evidence that Dorian faked her own death years ago and took on a new identity to escape tax fraud charges. This discovery explains why she was so desperate to stay hidden and why Mae was protecting her. Throughout this process, she hints at being there during the signing of Ernest’s will, which was thought to be nonexistent. The fifth day objective becomes to find the will.

Day 5 – Alice’s Will

On the final day, the player learns that Alice, who has been caring for the farm, believes she deserves it more than Calvin. She teamed up with Caleb to steal the original will and forge a new one. After gathering clues and presenting the case, the player proves the forgery.

The Ending Twist – Ernest Returns

Just as the player jails Alice and Caleb, they find the real will. When the player is about to read the will, something shocking happens: Ernest walks in alive. It turns out he faked his death as a test to see who truly cared about the farm and who could be trusted. Lucy, the ghost who guided the player from the beginning, thanks you for helping to uncover the truth. Ernest then gives the farm to the player, saying they’ve proven themselves to be the one person who actually stood for justice.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Design and Process

System Model

Design Choices

In an effort not to repeat many of the design choices already highlighted in this report – such as single-player, story-first experience, low-pressure and untimed gameplay, real narrative consequences, visual and environmental story design, and accessibility choices – I’ll expand on a few design choices that have not been discussed in detail below:

Narrative-Relevant Clues

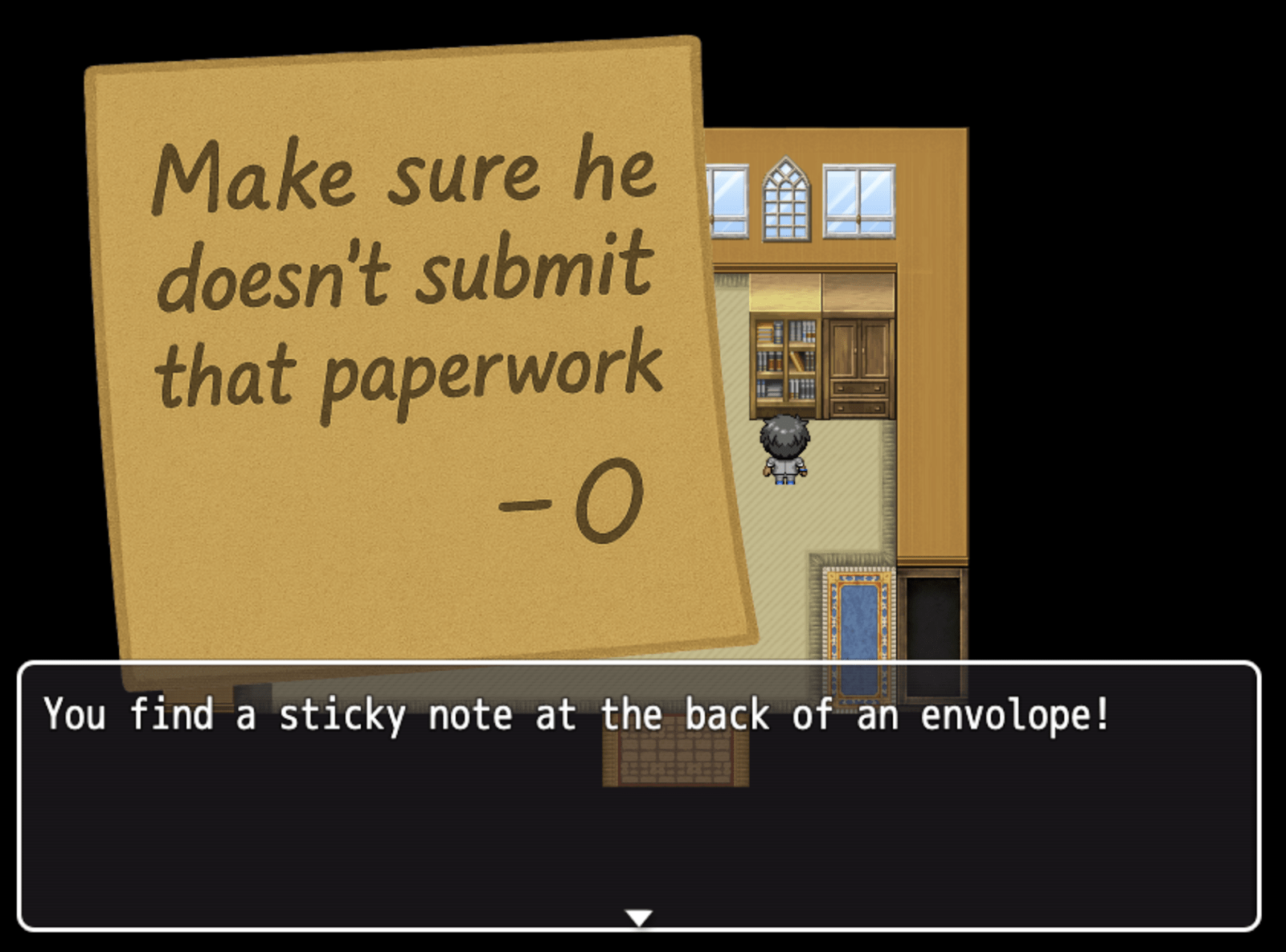

One of our biggest design priorities was making sure that every clue connected directly to the story. Instead of random items that lead to the mystery like an escape room, we made sure that all the items were realistic to the space, and showed real hints that said something meaningful about the characters, relationships, or mystery. These included things like a torn poster, a hidden calendar, a postcard, or a trashed sticky note. Even for the minigames, we kept them relevant to the game – figuring out a lock combination, (future) finding an object in a messy room, piecing together torn pieces of paper, etc. We did this so the player would feel like they were in the story during the game, and make the outcome more rewarding. It also allowed us to create compelling evidence choosing for the courtroom scene.

Clue-Dependent Dialogue

Another major design choice was building a clue-dependent dialogue system. This means that what characters say changes based on what the player has already discovered. For example, some dialogue only becomes available after you find a certain item or speak to another character. The way we envisioned this is that it makes the world feel more real, as you can confront players about what you have found, interact with them multiple times, and get tangibly and quickly rewarded for exploring. It moreso reflects real investigations, where new information changes how people respond and what you can say.

Integrating Images into Clues

To make clue discovery more tangible and real, we embedded images directly into clue interactions. Instead of just showing text descriptions, players see actual in-game photographs, fragments of documents, or posters when they uncover key evidence. This makes the clues feel more physical, like they were really discovered in the real world, and adds visual storytelling to build the narrative and atmosphere.

Minigames

To break up the pace of talking and clue gathering, we included minigames that fit the world and characters. We liked this as a way for players to solve micro-cases within the larger case, as well as interact with the game in a different way. For our playtest, we were able to implement one minigame: unlocking a coded lockbox hidden in Calvin’s room with his birthday as the passcode. This was a lot of fun for the playtesters, and we have many more ideas for minigames that would be narratively-relevant, as mentioned before, so we would love to have lots of these throughout the larger game.

Tone Construction

The visual and sound design of Ernest’s Estate was intentionally made to create a sense of mystery, unease, and anticipation, but mixed with the quiet exploration we discussed. The pixel-art aesthetic makes the game inviting and provides the realism to draw someone in, and our color tint as well as space design helps make it feel less cheery and innocent than a standard pixel-art game. The background music is calm enough for it to stay playing in the background throughout the game but adds to the mysterious aura of the place. The images have dark tones and simple colors – the sticky note is a light brown in a dark bookshelf as opposed to bright yellow on a refrigerator, for example – feeling real but suspicious. The characters themselves look slightly shady, like they have something to hide. This is reinforced by the way they speak to the player, with sharp tones, grunts, and anger. Overall, each of these pieces were chosen intentionally to convey the tone and feel of the game we created.

Development Process

We worked in parallel, building the game map and gameplay on RPG maker while also working on a physically-printed story. That allowed us to playtest the story early and divide responsibility, and put them together after both pieces worked individually. Then we built out the functionality on RPG maker, which took a long time to get right. It involved a lot of small things – figuring out how to make items and characters interactable, designing different sprites, designing every room, adding music, removing extra default settings from view, adding images and banners, and a ton more. In the middle of all of this, RPG maker would constantly crash on Macs, even after paying $80 for it to be installed!, so we had to constantly save any changes and push them on the github. And we lost one of our developers, but everyone stepped up to the plate! At the end of all of this, however, we had a great working first day.

Iteration History

Iteration + Playtest 1 & 2 (5/6 and 5/8)

We cleaned up the story, premise, and scope a lot through the first two playtests and concept doc submission. In this first week “playtests,” we didn’t have anything playable yet, so we showed people the concept doc narrative and asked what they expected to see, what they were excited about. Then we presented our ideas for what we could implement and asked people to say what they would want to see in the game, and how they would feel about adding that element.

Through this, we learned what excited people most: solving mysteries, uncovering secrets, and seeing characters betray each other – essentially the drama. They wanted to investigate more than just Ernest’s story, but wanted to find something about all the characters, to add more drama and twists. Our original idea had two players exploring separate worlds and switching between ghosts, but we realized it would be too hard to implement and might distract from the story. Instead, we focused on a single-player narrative with a central mystery and one ghost character who helps guide the player. We also started thinking more about the lawyer character—why they’re here and what motivates them emotionally to take on this case, as that was something pointed out in section and in class. We also got verification that people liked the concept of having to prove things in the courtroom in the evening.

Iteration + Playtest 3 & 4 (5/13 & 5/15)

For our second week playtests, we built a physical prototype using paper clues – little booklets that players could pick up and try to piece together. This helped us get a sense of how people would move through the story, what types of clues worked best, and what kinds of logic they expected to use. Players were excited to explore, but they also solved the puzzle quickly and simply, showing that we needed more clues, more complexity, and better ways to tie the story together. They also wanted more player interaction – they didn’t like that they couldn’t interact with Mae just because she ‘wasn’t relevant’ to this storyline, they wanted to discover that for themselves.

The feedback also helped us realize that clue order matters a lot more than we thought. Some clues needed to come after others to make sense or avoid being too obvious. There needed to be multiple clues to explore at each stage to avoid it feeling like the player wasn’t truly exploring.

Iteration + Playtest 5 & 6 (5/20 & 5/22)

By our third week playtests, we had built a working digital version of the game in RPG Maker. Players could now explore the farm, talk to characters, and find their first clues. This playtest showed a TON of problems with the game. Many players didn’t understand what they were supposed to do. Clues were too easy to find and not very satisfying to connect. We also had several bugs and issues with navigation – players sometimes got stuck or clues activated themselves. Overall, this felt like the MVP of the slice we were making, and now we had a lot to fill in to make it a true slice.

This gave us a lot to improve on. The overall story still seemed interesting, but we needed to better connect the clues to each other and build out the storyline and evidence system. We needed to significantly improve the clarity, overall game design, and vibe. We needed to add more player agency with different dialogue options, along with music in the background.

Iteration + Playtest 7 & 8 (5/27 & 5/29)

In our week four playtests, we made a bunch of major improvements to the game based on earlier feedback.

We added our first minigame – a lockbox hidden in Calvin’s room that could be opened by using his birthday. The clues overall were improved, too. They were harder to find and felt more connected to the story, but some of them still triggered too early and made the mystery too easy to solve. We added background music and redesigned the visual look of some of the rooms, getting closer to the tone and aesthetic we imagined. We also worked on making character dialogue more responsive – certain characters now said different things depending on which clues the player has already found, which made the world feel more real.

At the end of the playtest, players could reach the courtroom and submit evidence to get a result. But even though technically the system worked, the actual understanding of why the courtroom was important, where items were in evidence, and how to access them was still unclear. Part of this issue was because we saw that everyone just clicked past the onboarding, because it was long and text-heavy. We worked on changing this for the next playtest, focusing on the things we spoke about in the onboarding section, especially since we wanted to make players feel like they ‘won’ after the courtroom scene.

Overall, these playtests felt like a big step forward. The game was starting to look and feel like what we had envisioned from the beginning. There were still bugs and confusing parts, but it was finally coming together.

Iteration + Playtest 9 (6/3)

Our fourth playtest finally felt like the game we were trying to make since the beginning. We completely changed the onboarding, making it natural and integrated in the game by embedding it into the gameplay, as described in that section. Overall, this gameplay went significantly better and we got to see the playtesters reacting to the story and solving the mystery.

The playtest also showed a lot of small things that should be fixed. We cleaned up clue dependencies, ensuring that some conversations or items only unlock once certain clues are found. This made sure players didn’t discover information too soon through chance, but required more logic to solve. We saw some bugs with words being cut off and dialogue being prematurely activated. We also saw that we needed to fix the courtroom scene a lot – they liked it a lot, but we had to explain how the controls worked as well as how evidence submitting happened, since it wasn’t clear. Based on this, we re-categorized all the evidence as consumable, so that it would disappear when used in court. We also added the objective to the top right hand corner, added a family tree, and cleaned up the ending to feel more complete.

Final Playtest (6/6)

This really felt like everything came together from above! The game felt really cohesive, and it was fun to play. We playtested both with friends and ourselves. We’re excited for you to play the game!

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Annie and the teaching team for all your help throughout the project!

Generative AI was used in creating images for the game.

RPG maker was used to design the game.

Itch.io has been used to host the game.