Created by Justin B, Joaquin Galindo, Em Ho, Aimen Ejaz, and Sebastian Blue

Super sweet HTML buttons created by Amy Lo’s team for their P2 writeup

Artist’s Statement

Clearing began with a simple question: what would it feel like to play through grief, not as a metaphor, but as a place? From the beginning, we knew we didn’t want chaotic or fast-paced gameplay. We still wanted combat and coziness to be our main game mechanics, but we wanted it to feel intentional, emotional, and calm. The focus was on creating a quiet, strange little world where reflection and mood came first.

You play as a spirit fox, reborn from stolen forest magic, the theft of which is causing the corruption in the land, navigating a landscape that’s beautiful and broken. Each region represents a stage of grief, and every creature you meet reflects a different way of coping. We designed the mechanics: fireball casting, and cleave to mirror emotional states. The goal isn’t to “win” but to understand.

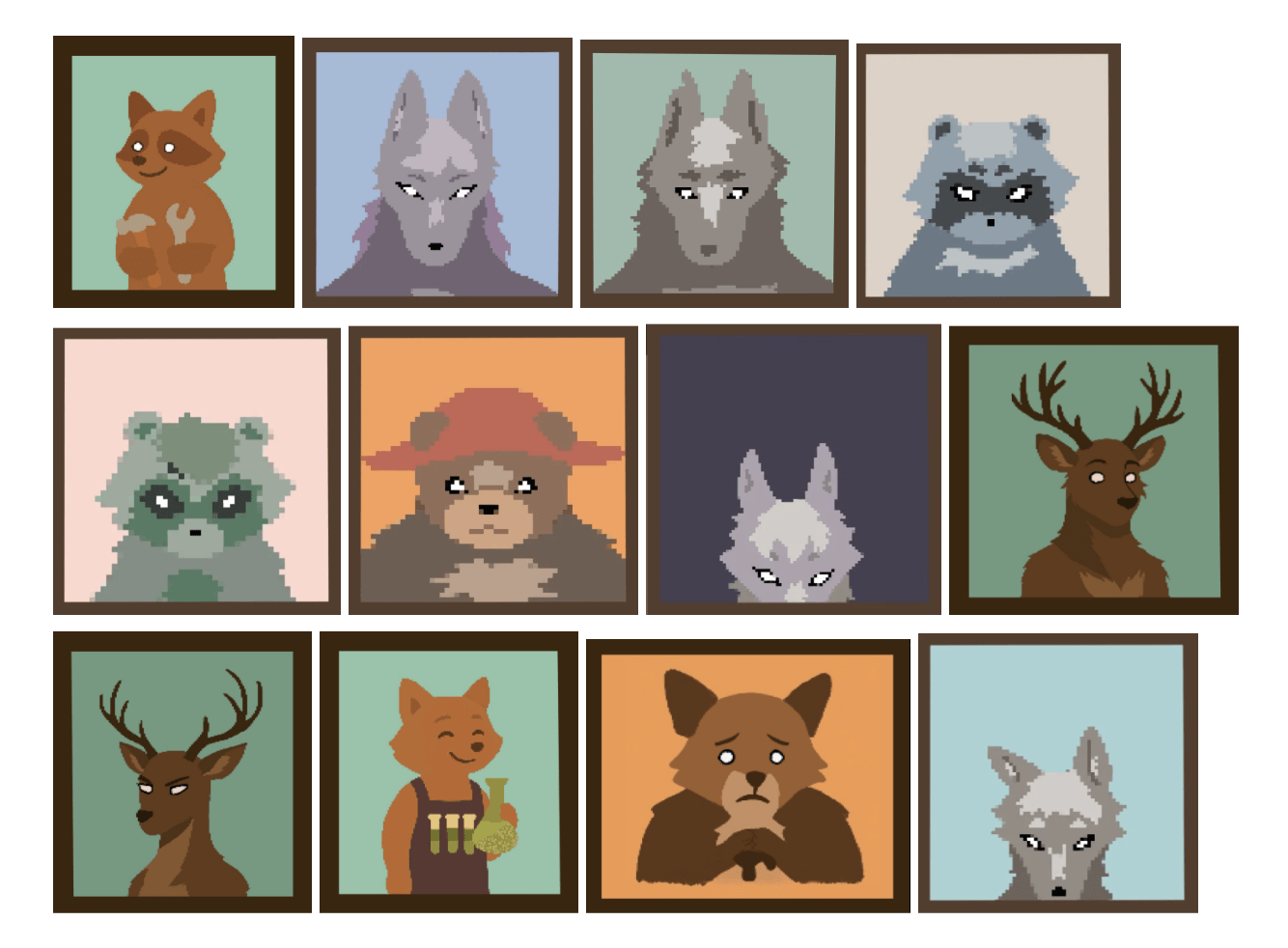

A lot of work went into tone and mood. Characters were hand-drawn, pixelated, and dropped into a cutesy 3D world that progressively gets more spooky and overgrown. Custom music was composed to match the game’s atmosphere, from quiet wind to distorted lullabies. The result is a game that feels soft, cutesy, and cozy. We call it critter forest energy.

This game is meant for players who don’t mind slowing down, sitting in ambiguity, and piecing things together. If Clearing does its job, players won’t just remember the story, they’ll remember the feeling.

Target Audience

Clearing is a serious game, and takes mechanical and narrative inspiration from games like Breath of the Wild, Hollow Knight, Super Mario Galaxy, and A Short Hike.

The game might be rated E10+ for its mild violence and heavy themes, but older players who have a deep appreciation for rich game narratives and the patience to slow down will enjoy this game most.

MDA

At the core of strong game design lies an intentional and effective connection between the implemented mechanics, the dynamics they create, and the broader aesthetics they inspire throughout the entire playthrough. This concept is captured in the Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics (MDA) framework created by Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc, and Robert Zubek. A more nuanced discussion of our game’s mechanics and their purposes exists throughout this write-up, but we felt it would be important to present a concise summary of how the mechanics in Clearing accomplish our goals for the game.

The mechanics of Clearing are simple: walk, jump, cleave, sneak, fireball, talk; the enemies are aggressive but not high-energy; the combat is challenging but slowed, and far less difficult than the combat in games that pride themselves on difficulty. We give the player various ways to interface with our game, but soften the intensity of that interaction to a minimum through intentional pacing of cooldowns, movement, and physical scale. By slowing the experience, playing can interface with the game while leaving room to experience the world around them. They aren’t so focused on the mushroom in front of them that they can’t see the tall trees or the grass flowing in the wind. The homeworld is devoid of obstacles, leaving the player free to spend as much time as they like speaking to the villagers. All of this ties together to create an experience rich in narrative and discovery, two aesthetics from the MDA that we resonate with deeply.

🦊 Our Game At A Glance

Key Mechanics

At its heart, Clearing is a slow, exploratory game where movement and emotion are tightly linked. You play as a small spirit fox navigating a forest filled with memory and loss. The mechanics are simple but expressive:

- Fireball (F): A ranged spell that lets you lash out from a distance, useful in combat, but also symbolic of emotional release.

- Dialogue (I): Speak with the creatures of the forest. They won’t tell you everything, but their words hold clues, fragments, and feelings.

- Movement: Use WASD to move, Space to jump, Shift to sprint, and C to crouch.

You’ll need to: - Jump and double jump across broken bridges and collapsed roots

- Sneak past corrupted enemies without being seen

- Watch for cliff edges and soft water hazards that slow your progress

- Use movement as both navigation and storytelling, it’s how you feel your way through the world

Narrative Architecture and Use of Space

Narrative Themes

You play as a fox, but not just any fox, you’re the leftover spirit of something broken. Everything you meet reflects grief in some form: guilt, memory, denial, regret. The villagers you find have their own stories, and some are ready to share them, while others won’t make it that easy.

- Characters like Osric, the quiet elder; the Capreo sisters, who finish each other’s sentences; and a mute bear who only gestures, all give you small pieces of the truth

- The forest doesn’t want to be saved, it just wants to be seen.

The story unfolds slowly. There’s no set order, and you’re free to explore and make sense of things in your own way.

Scope

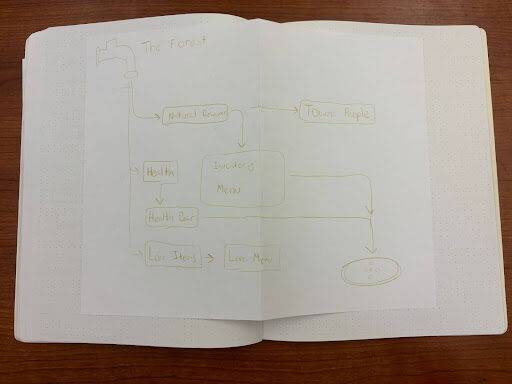

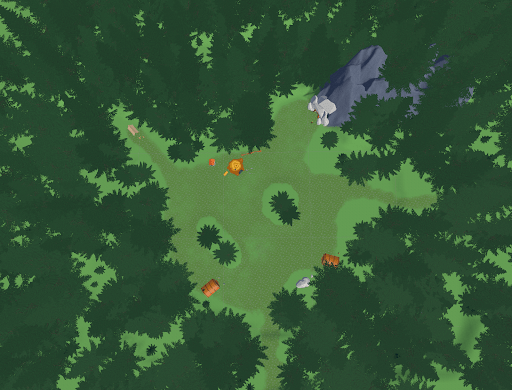

For this project, we built a vertical slice of Clearing that captures the core gameplay loop shown in our system diagram. Rather than a full MVP, this slice focuses on the emotional tone and central mechanics that define the game.

Players begin at the start of the game, where they wake up in a clearing, learn the basic controls, and get a taste for the combat and platforming. At the end of this tutorial world, they enter the homeworld, where they can talk to NPCs and receive narrative setup. This vertical slice shows the first taste of gameplay and the first bit of narrative.

If extended, the game would see the introduction of the Spirit Shift gameplay mechanic and other battles. The player would also rescue villagers, adding shops to the homeworld and unlocking new interactions.

This slice allows us to test how story, movement, and combat interact, and provides a strong foundation to build upon in the future.

Key Plan Choices

Aesthetic Style

We wanted Clearing to feel like a quiet little digital cutesy cozy story. The characters were all hand-drawn and then pixelated to give them a soft, cutesy feel. They’re small, expressive, and simple, like little critters you might find in an old illustrated storybook. We have a total of 12 unique characters.

In contrast, the world is fully 3D. This increases immersion and allows for greater variety in combat and platforming. As the player explores beyond the village, they encounter a variety of scale-defying structures, like anthill mineshafts, butterfly churches, and living tree hollows. In areas where there’s corruption, we see animals and plants acting strangely, surrounded by purple particles and corrupted ground. We aimed to evoke a sense of wonder, exploration, and slight unease.

Our UI matches that mood, controls are displayed on a forest signboard, dialogue boxes feel handmade, and nothing is overly artificial. It’s a space that feels warm, but slightly worn.

Sound & Music

Sound in Clearing was built as a core narrative element rather than just a polish layer. Each region of the game features its own looping musical theme, with seamless transitions between forest and hub spaces. Although we explored a system to fade in percussion during dialogue, the final implementation focused on layered ambient music that reinforced each scene’s tone. Environmental sounds like footsteps, running water, mushrooms, fireballs, and enemy presence were spatialized in 3D using FMOD and Unity, with attenuation curves and listener placement calibrated to create a realistic sense of proximity and space. Punching and jumping sounds were also customized by movement state, and a centralized AudioManager controlled volume sliders and scene transitions. These sound systems were built to enhance the quiet tension and atmosphere of the game – helping players feel immersed in a world that breathes, mourns, and slowly heals.

Forest Music

Village Music

Dialogue

To highlight the narrative-driven and character-driven aspect of the game, we wanted to highlight our dialogue system. We did this by creating dynamic dialogue trees in YarnSpinner, adding portraits and names to dialogue boxes, and indicating what characters have new dialogue with an “!” UI element. Dynamics dialogue that responds to who else the character has spoken to, makes the world feel alive. Portraits and names help make the characters feel more real and help the player remember who’s who. Lastly, the “!” dialogue element (incorporated because of feedback) helps players find who they need to interact with. It helps them know who they can talk to get more information, while not railroading them into speaking to characters in a particular order. It provides freedom and guides curiosity at the same time.

Onboarding

Inspired by the video on Onboarding in PvZ, we wanted a tutorial world that modeled the following characteristics:

- Teaches mechanics effectively (duh)

- Turns learning into an active, playful process

- Introduces mechanics as they become necessary

- Don’t teach something only once

- Demonstrates adaptive messaging, so that experienced players don’t feel condescended

Our game’s onboarding is embedded in the first level of the game. The player wakes up knowing nothing about the game (as intended), and they learn how to play alongside the character, both taking their first step through the unknown forest.

After learning to jump over a few obstacles, the player encounters combat with two shrooms, static enemies that fire slowly and deal little damage. The player also gets a checkpoint right before, meaning that if they die, they don’t lose any progress.

Later on, the player runs into two more shrooms, this time in a narrow strip through a lake of deep water. They have less room to run and jump to dodge, so they have to learn to sneak to avoid drawing attention. This forces them to learn another way of dealing with enemies, in a slightly harder environment, while keeping the challenge pretty low. Again, they have a checkpoint right before.

Lastly, the player encounters a final boss surrounded by shrooms. They need to defeat the boss before traveling to the homeworld – a stress test that makes sure that they understand how to fight enemies. This third combat puzzle introduces the Fireball, a ranged attack that can help them take out enemies from afar. By now, the player should have some experience moving, jumping, sneaking, and sprinting. This puzzle gives them a chance to apply all the tools that they’ve learned in combat before they finish the tutorial.

Altogether, these incremental introductions ensure that the player gets to interact with and enact the tutorial – rather than being forced to read a manual. Furthermore, it never overwhelms the player with too much information at once, making sure that they have a chance to learn each mechanic before adding a new one. The multiple opportunities to experience combat also provide the player a chance to revisit learned mechanics.

An extra touch that helps make the tutorial feel even more smooth is the adaptive messaging. Each of our tutorial tips is implemented with a TutorialTipZone, which fades in and fades out text as the player enters and exits. However, the TutorialTipZones also have an adjustable delay before showing the text. For basic controls like [WASD] to move and [space] to jump, we set the delay to 5-10 seconds, so that players who breeze straight through never even realize there’s a tutorial tip. On the other hand, players who are confused and can’t find their way past an obstacle will see the tutorial tip appear after trying once or twice. So TAs, if you don’t see any tutorial messages pop up, it’s not ‘cause we omitted them – it’s ‘cause you didn’t need them 😉

Design Process

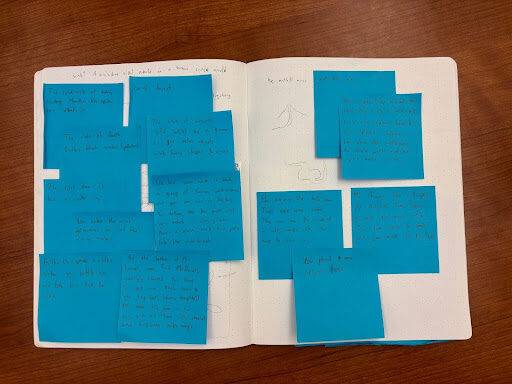

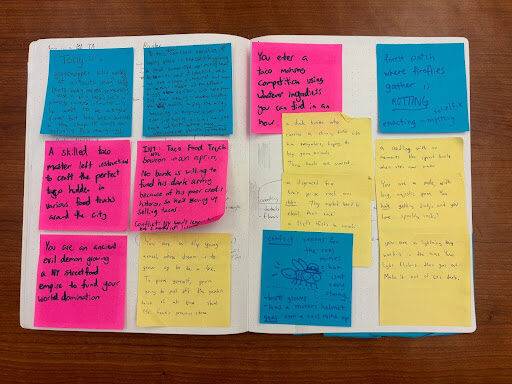

Early Brainstorming / Ideating Visual Artifacts

Initial Decisions

Our team for this project formed around a collective interest in a “cozy forest magic game.” One member was excited about implementing some form of combat, and another was interested in creating a home base where the player could find safety and comfort away from the harsh wilderness. We decided to designate these as required elements of our game.

With a selected theme and two required mechanics, we already had a loose idea of what playing our game would feel like for the player. Knowing this gave us the freedom to spend our early ideation time on the game’s narrative.

As part of an in-class exercise, what started as a silly narrative about the “Fox Mafia” and their reign of terror in the forest world turned towards the Mafia’s leader and his daughter. As the story evolved, we decided the daughter had recently passed, and that the Mafia stole magic from the forest to bring her back to life.

After a collaborative moodboard exercise, we realized that a violent Mafia had no place in what was otherwise a slow, thoughtful game of intrigue, rather than one with high energy or drama. The mafia boss just became a father, desperate to revive his daughter no matter the cost.

In our story, the main character’s father took her into the woods. Upon using the forest magic to heal her, she suddenly disappears. Later, she awakens in a clearing with no memory. Navigating an unknown path through the forest, she encounters corruption blocking her path. The forest magic her father stole for her has given her power, and she uses it to defeat the corruption. Eventually, she finds her way back to a town.

Where should the tutorial go?

Well, according to the story, she wakes up in a clearing and must journey back to civilization. Let’s teach the player the mechanics while teaching the character that she has power and that there is corruption in the forest.

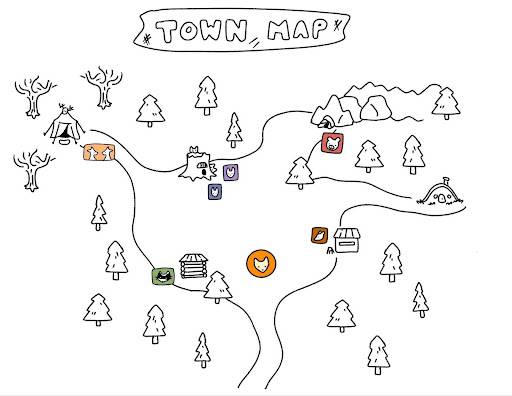

What should the first level be?

According to the story, she finds a small village and talks to the villagers to try to learn what is wrong with the forest and who she is. Let’s build a village!

Frontloading our worldbuilding and narrative arc ahead of time streamlined our creative process. When the village was finally built, it looked just like we imagined it.

Iteration History

Playtesting and Iteration History

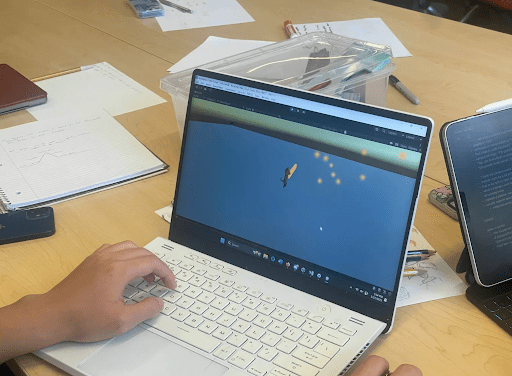

Throughout development, we conducted eight structured playtests, each designed to highlight specific gameplay elements, identify usability pain points, and clarify our game’s narrative direction. Our iterative design process involved closely observing players, capturing their immediate reactions, and implementing precise adjustments to improve player experience.

Playtests 1, 2 & 3: Early Movement and Dialogue Systems (May 16, 20 & 22)

In our first playtests, conducted with our classmates, we evaluated initial movement mechanics and introductory narrative interactions. Players initially found the movement amusing, especially enjoying the playful double-jump, but quickly became frustrated with unclear camera controls and ambiguous environmental boundaries. One tester humorously remarked, “the physics remind me of sheep simulator,” highlighting an overly chaotic and uncontrolled feeling. Additionally, players consistently struggled with figuring out the purpose of the central hub space, asking, “I’m not sure the purpose of this space right now.” Dialogue tests, while intriguing, led players to request clearer story indicators and a text-skip feature, as the exploration felt slow and unfocused at times.

Specific improvements:

- We expanded the explorable hub space, adding clearer environmental pathways to guide players more naturally.

- We implemented straightforward UI prompts for camera zoom and rotation controls, greatly enhancing usability.

- We outlined clearer objectives in dialogue and planned for future implementation of dialogue skipping to keep players engaged without frustration.

Playtest 4: Combat Mechanics and Player Controls (May 27)

Our next round involved individual sessions with playtesters D, R, and Y, focusing deeply on combat interactions, player control clarity, and camera sensitivity. D immediately struggled with camera settings, initially describing them as “confusing” and “overly sensitive,” noting the camera would dip awkwardly, and even clip through walls. R also remarked that the camera felt “very, very high sensitivity” and added frustration at delayed responsiveness, saying it “makes it harder to control.” Y provided humorous yet useful feedback on jump mechanics: “Why can I lowkey fly?” Y also struggled significantly with aiming fireballs, ultimately suggesting, “maybe if there were a crosshair?”

Specific improvements:

- We refined the camera controls, reducing sensitivity and implementing adjustable settings based directly on player feedback.

- Added an aiming crosshair and clearer visual feedback for combat to greatly improve precision and satisfaction.

- Introduced explicit UI prompts for overlooked mechanics like sneaking and punching, clarifying combat options early in gameplay.

Playtests 5 & 6: Tutorial and Objective Clarity (May 29 & June 2)

These tests, involving a classmate and a TA, targeted our game’s onboarding, clarity of objectives, and UI interactions. The classmate notably expressed strong frustration with the lack of immediate combat opportunities, repeatedly exclaiming, “I want to kill something!” and “Why can’t I burn things to the ground?” He humorously tried attacking friendly NPCs, underlining a clear mismatch in combat expectations. Amy highlighted significant confusion in the homeworld, frequently losing track of NPC interactions and bluntly stating, “I’m kind of lost.” Additionally, both testers specifically struggled with right-click camera controls, Amy directly suggesting we needed to “change how the camera controls work.”

Specific improvements:

- Clearly paced early-game combat introduction, ensuring players understood when and how combat would occur.

- Improved NPC interaction indicators and added dialogue progress tracking, preventing repeated confusion.

- Fully redesigned right-click camera mechanics for more intuitive player interaction and comfort.

Playtest 7 & 8: Final Integration and Polish (Final In-Class & June 4)

Our final playtests with classmates tested our nearly-complete game, focusing on the integrated gameplay experience. They particularly enjoyed the forgiving checkpoints and overall coziness, remarking that the game felt “really really cute” and “cozy,” yet had difficulties with overlapping dialogue zones, struggling to recall key characters like Osric and the Capreo sisters. One of them provided insightful feedback about player expectations around environmental interactions, stating specifically, “I thought fireball would destroy the wood branch at the start of the level.” Additionally, they disliked restrictive invisible walls, emphasizing that they limited his exploratory enjoyment.

Specific improvements:

- We explicitly delineated NPC interaction zones and adjusted dialogue triggers to avoid confusing overlaps.

- Replaced invisible walls with visible, logical environmental barriers (like clearly defined natural boundaries), enhancing player exploration.

- Added incremental onboarding for essential controls (movement, punching), ensuring players felt clear about fundamental interactions from the very beginning.

- Added trees where there were invisible walls to more clearly set expectations about what can and can’t be explored

Each unique playtesting session allowed us to clearly pinpoint and resolve key challenges, guiding our game’s evolution from playful but unclear beginnings into a polished, engaging, and user-friendly final experience.

Conclusion + Takeaways

Clearing began as a small idea: a quiet, emotional game about grief and identity. Building a vertical slice let us focus on tone, mood, and core mechanics without needing a full storyline. We spent most of our time making the world feel alive, foggy forests, off-kilter movement, and characters that hint at deeper stories.

Playtesting helped us realize how much little things mattered: camera control, unclear dialogue cues, or even awkward jumps could break immersion. We learned to guide players more gently without over-explaining, and to balance charm with emotional weight.

If we had more time, we’d keep building: add more villages, deepen the questlines, and let players fully explore what it means to heal. But as it stands, this slice feels like a full breath of the game’s soul. Not everything’s polished, but it’s honest. And we’re proud of it.

Extra Effort:

Our team has made extra efforts in a few select areas to improve our performance. We are particularly proud of the following aspects of our project:

Custom Assets

- Custom Music

- Character Profile Cards

Technical Ambition

- Implementing FMOD for enhanced 3D audio

- Implementing Yarn Spinner for a professional-looking dialogue with conditional conversation trees

- Implementing a visual pixelation effect and other camera enhancements to change the look of the game

Expanded Narrative/World

- Worldbuilding beyond the scope of the slice to inform design and future

Extensive Polish

- Smooth and dynamic movement animations

- Advanced camera movement

- Music/Audio FX for movement and combat

Citation/Disclosure:

- Generative AI tools, such as GPT and Copilot, were utilized throughout the development process to write code and debug.

- Some visual assets, such as 2D textures, were modified or generated by GPT-4o. All other assets, including 3D models, sprites, and audio, were either downloaded from the Unity Asset Store or created by a member of our team.