Clash of Clans is a mobile game created by Supercell primarily for adolescents. While many adults play Clash of Clans, the game’s colorful, fantastical design and its position as an iconic “iPod-Touch-game” reveal its predominant user base as teenagers. Which makes it particularly concerning that deceptive design around in-app purchases pervades the game, which is free to play but fueled by a simple live service model. Both the shop and the game mechanics which encourage shopping are designed, including by the insertion of randomness, to promote purchase and user retention; this design, in the worst case, puts its players at risk of addiction, and, in the best case, simply detracts from the game’s promise of fun.

The shop uses strategies of obfuscation, frenzy, and randomness to coerce players into spending money, or more money than they expect. The shop is organized mostly around a currency called “gems.” While, since the addition of recent features, gems can now be accrued through free in-game mechanisms, the primary mode of acquiring gems is through purchase. The use of this intermediary currency makes it more difficult for the user to understand how much money they are spending when purchasing with gems. The gem purchases also leverage multiple deceptive design patterns for in-app purchases. The purchasable amounts do not align nicely with common purchases, like builder huts, and they offer bulk discounts (as seen in the first picture below), which encourage users to spend more money than they might plan on. Additionally, the shop features a “Special Offers” section, shown below in the second picture. This illusion of “randomness,” of luck in having a particular skin come through, and the transience creates a frenzy that makes players more likely to purchase. But why should players make purchases in the first place?

The design of the game creates “Pay to Play” and “Pay to Win” experiences that encourage players to make purchases for more than simply aesthetic reasons. The game’s play is organized mainly around raiding villages. Raiding others’ villages earns you resources, and others can steal your resources when raiding your village; these resources then enable progression by allowing you to upgrade your defenses or troops to better raid villages or respond to raids. While the player chooses what village they raid, the options presented to them — and, thus, to some extent the amount and type of resources they can earn — are random. Additionally, the opponents who raid a player’s village are random — and, so, similarly are the amount and type of resources they lose. This input randomness drives users to simply purchase these resources (see the first picture below) instead because your resource availability controls how and to what extent you can play the game — i.e. you “Pay to Play.” Purchases enable “Paying to Win” in that access to resources improves your bases and armies, giving you an advantage over your adversaries, and in that gems can buy invulnerability (see the second screenshot below). Players can quickly develop a reliance on this paid accumulation of resources and abuse it to chase the game’s fun.

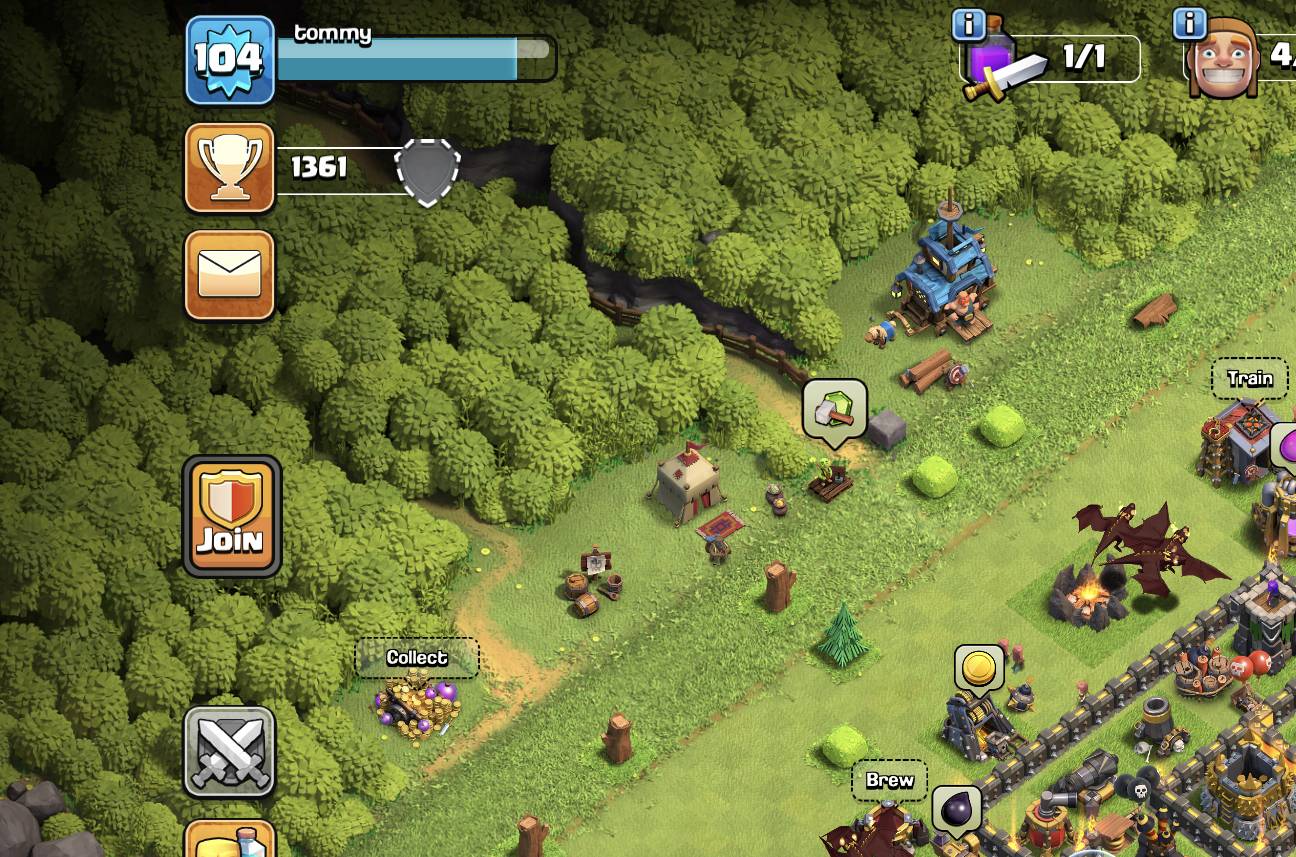

The success and adaptiveness of this live service model has superseded the game’s originally intended fantasy, challenge, and fellowship as its aesthetic and, seemingly, its design motivation. I played Clash of Clans extensively as a kid, but I haven’t picked up the game in probably five years. As many live service models do, Clash of Clans has continually added new content to elicit more money from its committed players, or, sadly probably more accurately, its addicted users. While this may also satisfy these committed players, my experience was that it detracts from the fun that I once had with this game. The overload of features, motivated by the game’s live service business model, has buried the core gameplay loops — the central mechanics from which dynamics and eventually aesthetics emerge. This makes it harder to engage with the essential part of the game that makes it fun. In the screenshots below, observe all of the assets around the main plot of land, which are all shallow additions to the core gameplay which occurs within the plot.

The design of the game itself and of the shop deceives players about their spending and puts them at risk of addiction. As I mentioned in the introduction, this is particularly immoral because the game’s target audience, or at least its primary user population, is adolescents. Adolescents are both more susceptible to deceptive/coercive designs around spending, and are likely to be less responsible with spending. While drawing the line for the permissibility of coercion in purchases is difficult, I feel comfortable saying Clash of Clans goes a step too far by exploiting teenagers.