Undertale is a single-player game developed by Toby Fox for PC (Windows, macOS, Linux) and various game consoles (Nintendo Switch, PlayStation, Xbox, etc.). The game’s target audience is fairly broad, appealing to players who enjoy indie-style RPGs that incorporate puzzles and combat. The overall narrative, revealed through interactions with NPCs, signboards, and other elements, conveys a lighthearted and humorous tone. This tone appeals not only to players interested in gameplay mechanics and dynamics but also to those who appreciate intricate details and humor-driven interactions. That said, the humor is likely most effective for teenagers and young adults, who may be more receptive to or familiar with the style of jokes used. The game’s story involves the player falling into the Ruins and needing to traverse the world to defeat Asgore in order to return home. Along the way, they must “fight” enemies and solve puzzles to progress to the final encounter.

The mechanics of the game are fairly simple, involving only a few keys on the keyboard (the arrow keys, Z, and X). Players interact with various monsters—characters in the game—by engaging in straightforward battles. During combat, players can choose to fight using a basic attack mechanic. To execute an attack, they must time a moving bar to land in the center of an “attack power bar,” sometimes followed by pressing the Z key again if they are using a glove-type weapon. While the early attacks rely on simple timing and button presses, the acquisition of different weapons and items later in the game introduces variety, keeping combat fresh and engaging. This prevents the gameplay from feeling repetitive, as players are not restricted to a single type of attack. Monster attack phases follow a consistent structure: the player, represented by a red heart, is confined to a square area where they must dodge incoming attacks. These attacks—humorously referred to as “Friendliness Pellets” by the player’s so-called “best friend,” Flowey—are unique to each monster, offering a dynamic learning experience and maintaining unpredictability. For instance, Flowey attacks with pellets, the Dogi couple may form a circle of hearts, and other enemies like Froggit or Doggo perform jumping attacks. The game also uses color creatively to affect gameplay. For example, blue-colored attacks require the player to stay still to avoid damage, adding an extra layer of complexity. This thoughtful design enriches the combat system, shifts the gameplay dynamics, and enhances the game’s overall aesthetic experience. In addition to these core mechanics, the game includes non-combat actions through the “Act” command, allowing players to interact with monsters in unique ways—such as talking, flirting, rolling around in the dirt, or performing other context-specific actions. These interactions vary from encounter to encounter, encouraging players to experiment and discover different outcomes. Players can also choose to spare their opponents, further expanding the range of possible gameplay strategies. This flexibility results in a highly replayable game, unlike many traditional narrative-driven titles. Players can approach the game aggressively—defeating every enemy to gain LV (“LOVE”) points—or they can take a mixed path, choosing to spare some enemies while defeating others. Alternatively, they can pursue a pacifist route, sparing all opponents and avoiding combat entirely. Each path leads to significantly different story outcomes: an aggressive path culminates in a final battle against Sans, a pacifist route ends with a confrontation with Asriel, and a mixed approach results in battles with both Asgore and Flowey. These branching narratives demonstrate how player choices directly influence the story, making Undertale a strong example of experiential learning. The variety of actions and the multiple possible outcomes not only enhance player agency but also encourage multiple playthroughs to explore the full depth of the game’s design and storytelling.

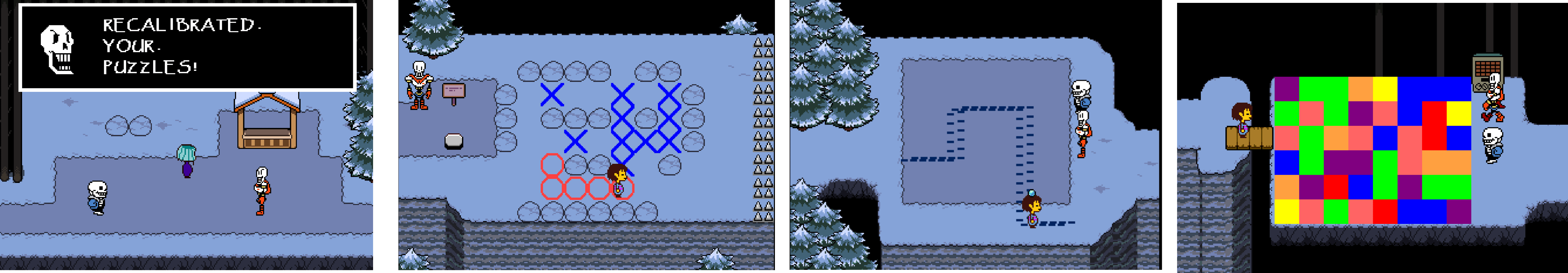

These design choices, however, limit accessibility for individuals with vision impairments. Dodging enemy attacks is already a challenging task, and visual impairments significantly increase the difficulty. Even with audio cues, effectively avoiding attacks remains a major challenge. A potential solution the developer could have considered is offering additional accessibility options. For instance, simplifying attack patterns—such as removing “stay still” (blue) attacks—or providing alternative feedback, like haptic signals through a game controller, could help. Vibrations could alert players when they are near an incoming attack, allowing blind or visually impaired players to better engage with the core dodging mechanic. These changes would enable players with visual impairments to more fully experience the mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics (MDA) associated with combat. Without such accommodations, these players may feel more inclined to follow the pacifist route, focusing on non-combat interactions like “Act” or “Spare” and potentially missing out on a significant aspect of the game’s design and emotional impact. Figure 1 illustrates the various types of combat scenarios in the game, including some of the unexpected and humorous outcomes—such as what happens when you pet Doggo too many times. These interactions add to the game’s charm and relatability, as petting a dog is a much more familiar and endearing action than fighting one.

Figure 1: Combat sequence in Undertale, illustrating how the game introduces the concept of fighting to gain LV (short for “LOVE”) points. The figure also features a selection of enemies that players encounter throughout the game. In the final panel, the player chooses to “Act” by petting Doggo, a guard character—an unexpected action that leads to a humorous and surprising outcome. This mechanic showcases how seemingly simple interactions can produce dynamic results, evoking feelings of joy, curiosity, and unpredictability. Such moments keep players engaged, prompting them to wonder, “What else can I do?” This effectively ties the fun of exploration and experimentation to the game’s broader themes, emphasizing personalized storytelling and the wide range of possibilities available to each player.

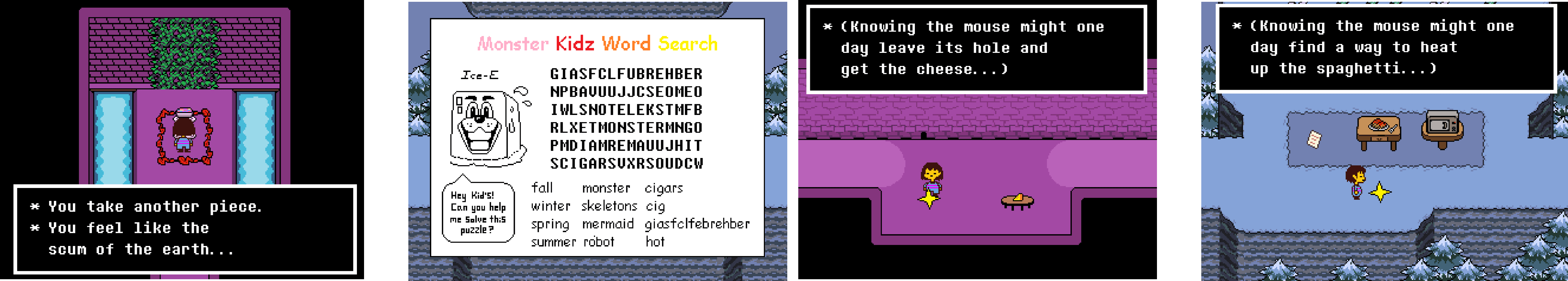

In addition, players can interact not only with various monsters (the characters in the game) but also with inanimate objects—such as signboards, books, and environmental elements—to gradually piece together the overarching narrative of the Ruins and the game as a whole. These interactions help players construct the game’s story, while also encouraging them to engage more deeply with its world through both narrative and formal elements. For example, players must often solve puzzles to advance the story (see Figure 2). These puzzles, while not particularly difficult, require players to pay close attention to their surroundings—such as finding a hidden switch or reading a clue from a nearby sign. Though simple, these puzzles serve a crucial role in supporting exploration, rewarding players who are observant and curious. Subtle cues, like a switch hidden behind a tree or narrative hints scattered through signboards or character dialogue, enrich the experience and motivate players to care about the game’s world. The game also invites players to engage with its sub-narratives—smaller stories connected to individual characters or items. For instance, the player is tasked with carrying a piece of a snowman to a faraway location, turning it into a narrative-laden inventory item. Early in the game, players encounter a candy bowl in the Ruins or a pile of smoked dog treats near a Dog Guard outpost. These small, often humorous or touching moments tie players more closely to the world and its characters. The accumulation of these details helps sustain engagement, encouraging players to keep playing to uncover more of the world’s depth. A final example of how Undertale uses formal elements to maintain interest is through its treatment of in-game resources. Locations such as the Spider Bake Sale or the ice cream stand in the snowy region serve as places where players can spend their gold (the game’s currency) to purchase helpful items. While functional, these elements also enhance immersion. For example, encountering an ice cream stand in the middle of a frozen landscape adds a humorous and self-aware touch—the joke about selling ice cream in an icy setting made me more aware of my environment and deepened my appreciation for the game’s playful tone. A final aspect that the game uses, is the promotion of smaller scale narratives of the game, which helps encourage the reader to explore the world and its elements. For example, the use of different dialog for save checkpoints, especially those for the mouse trying to get the food off the table, encourages the player to interact with the differetn elemtsn related to the mouse story, which helps engage the player with the world (see figure 3).

Figure 2: Puzzle sequences and player interactions that encourage exploration within the game world. This figure highlights an early puzzle requiring the player to find a hidden switch to solve the “circle and X” challenge. Through light environmental problem-solving and subtle clues, the game motivates players to pay attention to their surroundings. Additionally, the integration of humor within these puzzles helps maintain player engagement, demonstrating how simple mechanics can effectively support both gameplay and narrative progression.

Figure 3: Example of a save point dialogue featuring the mouse attempting to retrieve food from the table. These unique and humorous save point messages encourage players to engage with small narrative threads, like the mouse’s ongoing struggle, which enrich the world-building and strengthen the player’s connection to the game’s environment. Other subtle narrative elements—such as the candy bowl in the Ruins or Sans’ use of a crossword puzzle—also contribute to the game’s overall aesthetic and tone, reinforcing its humor and charm.

From an ethical standpoint, beyond the accessibility challenges faced by individuals with visual impairments, Undertale makes meaningful progress in its portrayal of racial diversity. Throughout the game, various monster races coexist and cooperate in their efforts to capture the human (the player), presenting a world where racial harmony among different species is normalized. This stands in contrast to older games like early editions of Dungeons & Dragons, which often depicted racial segregation or fixed traits based on character race. Undertale improves upon this by offering a more inclusive and integrated fictional society. Regarding the depiction of the body, the game’s mechanics limit the player’s actions to what one might reasonably expect a human to be capable of. For example, there are no superhuman or magical attacks available to the player by default. Instead, attack variations are based on the items the player equips—such as gloves or weapons—which is logically consistent with a human character. This adherence to physical realism can enhance immersion, as it prevents the player from feeling disconnected from the in-game logic. If a human character were suddenly able to perform impossible feats without explanation, it could undermine the believability of the narrative and game world. That said, a potential improvement could be the gradual introduction of new abilities based on cultural traits or learned experiences from interactions with monsters. For instance, players could unlock unique actions or attacks by engaging with specific monster communities or learning from them over time. This would not only preserve logical consistency but also add depth to the gameplay and narrative, allowing players to evolve in a way that feels earned and story-driven, rather than starting out with overpowered abilities.

In Undertale, the attacks used by different monsters are often logically tied to their physical traits or the items they carry. For example, a monster wielding a spear will typically have a spear-related attack, which aligns with the game’s commitment to internal consistency. This design mirrors recent shifts seen in modern versions of Dungeons & Dragons, where the game has moved away from associating learnable traits with a character’s race. While D&D still retains some physical traits (e.g., orcs having darkvision), this approach helps maintain a balance between realism and the effort to disassociate race from inherent biological abilities. Undertale takes a similarly thoughtful approach. It avoids assigning intellectual or behavioral characteristics to monsters based on their species. Instead, it emphasizes that monsters—regardless of their type—can fill a wide variety of social and professional roles. For instance, monsters such as the dog guards, Undyne, and Papyrus serve in military or guard roles, while Alphys, a lizard-like monster, is portrayed as a scientist. This reinforces the idea that monsters are defined more by their individual personalities and choices than by their biology. However, the game does impose some limits on the types of attacks monsters can use, basing them on physical characteristics—an approach consistent with D&D‘s treatment of physical traits. This strategy enhances believability without reinforcing problematic stereotypes. One possible improvement would be to allow the player to learn new combat skills based on their interactions with different monsters or communities throughout the game. This could deepen the connection between narrative and gameplay, allowing for a more personalized and evolving combat system that still respects the game’s internal logic and ethical stance.