Portal is a video game by the game developer Valve, which can be played on PC and console systems. The age range of its target audience runs from preteens / tweens to adults— though it wouldn’t be inconceivable to let even younger gamers play it. The beginning of the game eases players into the various puzzle mechanics, and the puzzles themselves have varying levels of difficulty and complexity that might be harder for a really young audience to navigate, but the game encourages experimentation by letting players move around and use the portal gun freely. This ability to experiment, which is further encouraged by the fact that dying only resets the level’s progress, gives players a lot more leeway in exploring the test chambers and failing, making the game more accessible to a broader range of players.

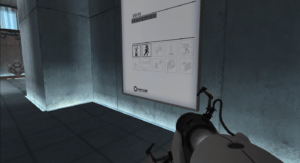

The other thing that might exclude a younger audience from the target age range of Portal, however, is the tone and setting of the game. Portal takes place in a futuristic laboratory facility. The design has its own quirks, such as the safety signs pertaining to the puzzles that decorate the walls, but overall the facility is very stripped down and minimalist compared to the bright and interesting visuals of a game like Angry Birds. The aesthetics it tries to evoke—the scientific setting, the feeling of being a test subject and being watched—are also things that might fly over a younger person’s head if they had not encountered these aesthetics in other media or real life beforehand.

The other thing that might exclude a younger audience from the target age range of Portal, however, is the tone and setting of the game. Portal takes place in a futuristic laboratory facility. The design has its own quirks, such as the safety signs pertaining to the puzzles that decorate the walls, but overall the facility is very stripped down and minimalist compared to the bright and interesting visuals of a game like Angry Birds. The aesthetics it tries to evoke—the scientific setting, the feeling of being a test subject and being watched—are also things that might fly over a younger person’s head if they had not encountered these aesthetics in other media or real life beforehand.

The core mechanic of Portal is the, well, portal that the player (and any items they can fit through the portal entrance) can travel through. These portals can be embedded into certain walls, ceilings, and floors of the facility through the use of a portal gun, which will open up one portal connection at a time. The portals of Portal alters the player’s perspectives on the puzzles and the game itself.

The core mechanic of Portal is the, well, portal that the player (and any items they can fit through the portal entrance) can travel through. These portals can be embedded into certain walls, ceilings, and floors of the facility through the use of a portal gun, which will open up one portal connection at a time. The portals of Portal alters the player’s perspectives on the puzzles and the game itself.

Something I found interesting was how I could only see my player character, Chell, through the portals. In the first level with the portals, as I was trying to figure out how the portal connections worked, I would walk through one and catch the tail end of myself leaving the room where I had just been.

These moments facilitate a third-person observance of Chell, since it’s a moment where the usually 1st person POV is subverted in order to allow the player to see the avatar responding to their controls in a way that’s more distant from the body. The view of Chell that these portals create subtly advances the game’s narrative and its themes of surveillance, which is further reinforced with the presence of viewing windows in the test chambers and the many cameras placed all around the environment.

These moments facilitate a third-person observance of Chell, since it’s a moment where the usually 1st person POV is subverted in order to allow the player to see the avatar responding to their controls in a way that’s more distant from the body. The view of Chell that these portals create subtly advances the game’s narrative and its themes of surveillance, which is further reinforced with the presence of viewing windows in the test chambers and the many cameras placed all around the environment.  Seeing Chell in the third person also opens the player up to a new conceptualization of the avatar—and therefore the player—in the space, as it invites them to approach their puzzle solutions by imagining the rooms in two different views.

Seeing Chell in the third person also opens the player up to a new conceptualization of the avatar—and therefore the player—in the space, as it invites them to approach their puzzle solutions by imagining the rooms in two different views.

Glimpsing Chell moving as I moved her also generated a very destabilizing experience, a little bit like being in a mirror maze. The immediate connection between the locations connected by the portals implies spatial continuity that exceeds player expectations of how movement and space function.  The portals behave unlike other modes of magical transportation, such as Minecraft’s Nether portals, which include a waiting period and a fade to black screen to signify transportation before the portal spits you out on the other side. Rather, only the glowing outline of the portal entrances delineate the boundaries of space that you are violating. Combined with the way that you can clearly see the state of the other side of the portal, in real time, Portal’s portals seem a lot like regular windows until the moment you step through, and end up somewhere totally different.

The portals behave unlike other modes of magical transportation, such as Minecraft’s Nether portals, which include a waiting period and a fade to black screen to signify transportation before the portal spits you out on the other side. Rather, only the glowing outline of the portal entrances delineate the boundaries of space that you are violating. Combined with the way that you can clearly see the state of the other side of the portal, in real time, Portal’s portals seem a lot like regular windows until the moment you step through, and end up somewhere totally different.

If you think of them like magical hallways, the connections the portals make complicate the space of test chambers by adding countless possibilities of these invisible “hallways” to the game’s regular navigation options. The dynamic of trying to visualize these paths, and making sense of the non-Euclidean perspective adds to the challenge of Portal’s puzzles.

Additionally, the disorientating effect of the portals also forms the basis of the game’s sensory aesthetic, which is secondary to the main challenge proposed by the puzzles. However, the sensations of portal travel—the anticipation of jumping into a portal on the floor, or the excitement of getting launched out the side of a wall—support the immersive and interactive fun of the puzzles.

Additionally, the disorientating effect of the portals also forms the basis of the game’s sensory aesthetic, which is secondary to the main challenge proposed by the puzzles. However, the sensations of portal travel—the anticipation of jumping into a portal on the floor, or the excitement of getting launched out the side of a wall—support the immersive and interactive fun of the puzzles.

Ethics:

Portal lives in a very self-contained universe, where the entirety of the world is contained within the ecosystem of Aperture Laboratories. This is beneficial to a cross-cultural playing experience, in many ways, as its futuristic and stripped-down setting means it doesn’t take a lot of cues from culture-specific knowledge, nor does it rely on them much to create its puzzles. A counterexample I can think of, for example, might be the game Storyteller, which uses Western pseudo-historical aesthetics and Christianity (like the level iterating on the story of Adam and Eve) and therefore does rely on player familiarity with these elements.

The main assumptions of knowledge that Portal makes of the players is their understanding of physics interactions, such as the idea that pressing down on a button—by standing on it, or placing a block on it—will exert enough force to push it, or that when GLaDOS talks about the momentum-preserving effects of the portals, it means that falling through one will launch the player some distance forward.  These assumptions are pretty difficult to extricate from the core of the game, but I think that it’s also a surmountable obstacle that the game teaches you in the earliest levels. As I mentioned above, the leeway Portal gives you to experiment also allows people who struggle with these assumptions to get a better handle on it.

These assumptions are pretty difficult to extricate from the core of the game, but I think that it’s also a surmountable obstacle that the game teaches you in the earliest levels. As I mentioned above, the leeway Portal gives you to experiment also allows people who struggle with these assumptions to get a better handle on it.