1. Identify the basic elements in a game of your choice (actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, players).

Maplestory:

Actions: Players are free to explore, move, and fight through a large open world, interacting with other players, NPCs, and enemies as they wish. They do this by clicking on other players/NPCs and utilizing their “job abilities”, movement/offensive/defensive/buff abilities unique to their class, through keypresses.

Goals: There is no one goal within Maplestory. Players create their own goals, whether that be becoming the most popular player on their server, leading the strongest guild, upgrading and star-ing their armor/weapons, perfecting their alchemy/blacksmithing/tailoring skills, acquiring the rarest title, spamming the server with costly global messages, getting a new time record on a boss, etc. Most players take on the goal of leveling their character to max, becoming as strong as possible, and repeating on a new character of a different class to unlock their “link ability”, a passive ability given to other characters a player has on their account, normally in the form of a very strong buff, like increased coin drops or experience value.

Rules: The clearest rule in Maplestory is the concept of ability cooldowns. You cannot use a job ability until you wait a specific amount of time for a given ability to be available again. Other rules come in the form of class-specific armors/weapons, class-specific quests, etc. While these rules are limiting, like mentioned in chapter 1, they also propel players to interact with Maplestory’s world in a specific way, and push players to find ways to minimize their downsides.

Objects: Enemies in Maplestory drop various different items, including armor/weapons, coins (meso), quest items, potions, experience badges, etc. Some of the aforementioned items help the player progress more easily, while others are necessary to unlock hard progression barriers.

Playspace: Maplestory mainly takes place in Maple World, a vibrant 2D planet with various different locations that the player can travel to.

Players: Players are individuals from around the world! Maplestory is region-limited, so in the US you usually only encounter other US players.

2. As a thought experiment, swap one element between two games: a single rule, one action, the goal, or the playspace. For example, what if you applied the playspace of chess to basketball? Imagine how the play experience would change based on this swap.

If League of Legends and Supervive, two MOBA/MOBA-like + battle royal games (respectively), swapped their playspaces, League of Legends would be in desperate need of a new goal, and Supervive would be in desperate need of new rules. League of Legends characters that can dash/fly across Supervive’s abyss would become way more valuable along with Supervive characters who can phase through/dash across league’s many, many walls. Since League is a 2-team game while Supervive is a 10-20-team game, League teams would need to find a new goal that does not require destroying the enemy team’s nexus before they destroy yours. Maybe League could allow for more than 2 teams to face eachother and adopt a battle-royale “last team standing” goal. Supervive could maintain its goal of being the last team standing in League’s world, but would require new rules that would also affect the playspace actually. Now that I’m thinking about it, this swap is pretty terrible and would leave both games in unplayable states without other changes.

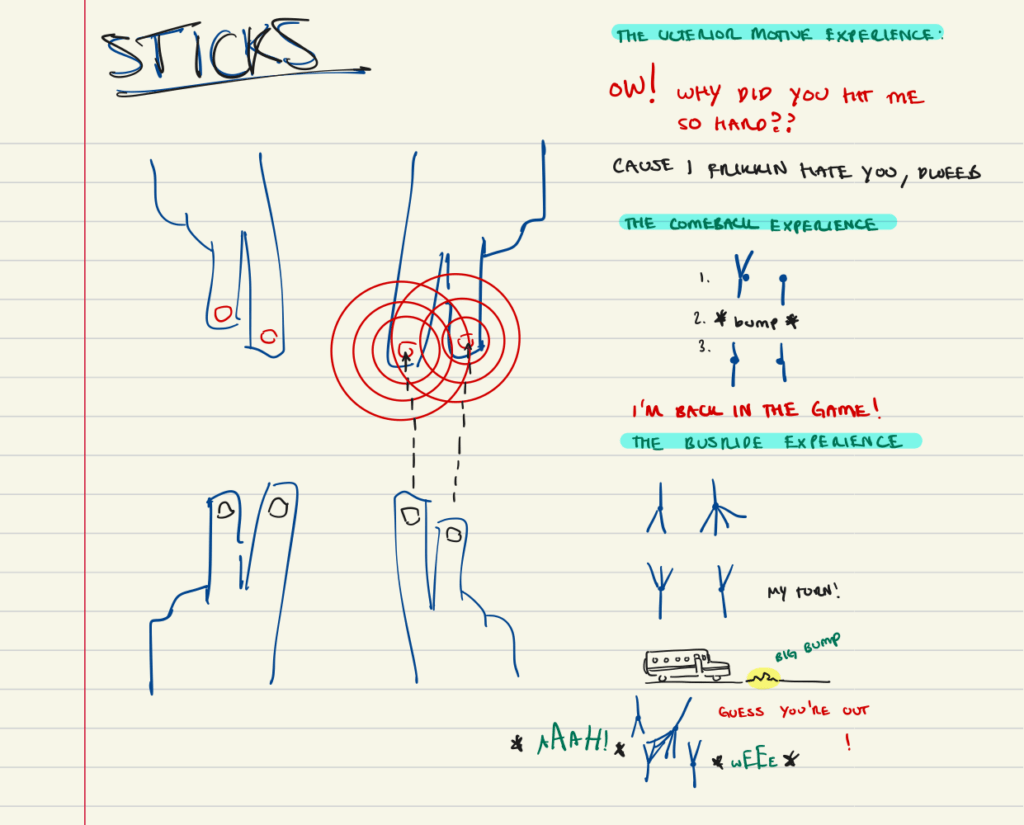

3. Pick a simple game you played as a child. Try to map out its space of possibility, taking into account the goals, actions, objects, rules, and playspace as the parameters inside of which you played the game. The map might be a visual flowchart or a drawing trying to show the space of possibility on a single screen or a moment in the game.

4. Pick a real-time game and a turn-based game. Observe people playing each. Make a log of all the game states for each game. After you have created the game state logs, review them to see how they show the game’s space of possibility and how the basic elements interact.

Team Fortress 2:

Game States:

For Payload…

- Offensive team pushing the payload forward

- Defensive team reversing offensive team’s progress by pushing the payload backwards

- Both team’s contesting the payload

- No members from either team are touching the payload, off doing other things (walking to it, killing each-other)

For Capture The Intelligence…

- One of the two teams is in possession of their enemy’s intelligence and is moving towards their home base.

- Both teams are in possession of their enemy’s intelligence and racing home to win.

- Intelligence has been dropped somewhere on the map by one or both of the teams because the player(s) holding it died.

- Both teams are not in possession of their enemy’s intelligence (busy defending/attacking/respawning)

Chess:

For Classical:

- White is winning, no one in check.

- Black is winning, no one in check.

- White is winning, white in check.

- Black is winning, black in check.

- White is winning, black in check.

- Black is winning, white in check.

- many more depending on how detailed you want to get, you could consider either side having forced mate to be a game state, either side being down a piece to be a game state, etc.

Although TF2 has way more game states, it actually seems to have less actually meaningful ones in comparison to Chess (meaningful in that they describe sufficiently different positions and states). To cover most of the possible game states in TF2, you only need a few general game state categories. This is without considering game states that are characterized by the players, however. One could consider having an AFK teammate in TF2 or a teammate that is trying to purposefully lose their own game states, both relatively doomed ones. I noticed that the game states I jotted down while watching gameplay i described rather objectively as opposed to with more emotion (tense team fighting, depressing blunder).