“Life is Strange,” was developed by Dontnod Entertainment published by Square Enix and is available on platforms including PC, PlayStation, Xbox, and Nintendo Switch. For this critical play, I played Life Is Strange on my iPhone.

“Life Is Strange” expertly blends mechanics with narrative to deepen the mystery genre, captivating a mature audience with its thought-provoking themes and interactive depth. The core of “Life is Strange” lies in its dual narrative approach, where the enacting and embedded narratives are conveyed through distinct yet complementary mechanics. This design choice masterfully weaves the theme of doubt and second-guessing with the task of piecing together the elements of the mystery.

In the enacting narrative, players navigate the world through Max, a high school student with the ability to rewind time and change her decisions. This mechanic is not just a tool but a reflection of Max’s personality—her hesitancy and reluctance to make bold decisions are mirrored in the player’s ability to undo and redo actions. As I explored this mechanic, I found myself questioning every choice, wondering what the other path might have been like, embodying the game’s pervasive theme of doubt. This ability allows players to experience different outcomes, pushing the narrative forward in unique ways and showing that the path to resolution is not linear but filled with potential twists.

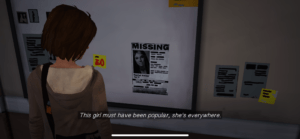

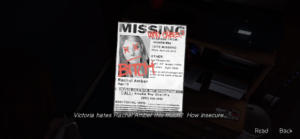

Simultaneously, the game’s embedded narrative unfolds through interactions with the environment. Each object in the dense, detailed spaces of “Life is Strange” holds a piece of the story, particularly the mystery of Rachel’s disappearance.

As I inspected missing person posters, snooped through character’s personal belongings, and interact with other elements, they gradually piece together the backstory and understand the interconnected lives of the characters.

This mechanic encourages a meticulous exploration that rewards curiosity and patience, aligning with the game’s theme of uncovering hidden truths. The synergy between these two sets of mechanics—time manipulation and environmental interaction—creates a rich, immersive experience. Players are not just observers but active participants in the narrative. They experience the uncertainty and complexity of the characters’ lives while assembling the scattered pieces of the overarching mystery. This dual approach allows “Life is Strange” to stand out in its genre, offering a deeper, more nuanced exploration of its themes compared to similar games.

In the carefully designed spaces of “Life is Strange,” the architecture of the setting plays a pivotal role in guiding the story’s progression. The limited expanse of explorable areas, such as the small, cluttered rooms of Blackwell Academy and Chloe’s house, is balanced by the dense detail and multitude of interactable objects. This design choice not only heightens the sense of intimacy and immediacy in the game but also subtly directs players through the narrative. As you are often tasked with specific missions, like finding a particular artifact, the environment becomes a narrative compass, leading you to interact with objects that reveal both minor details and major plot points. This approach ensures that players remain within the narrative’s flow while still feeling the freedom to explore and uncover the story at their own pace.

The game also features both literal and figurative loops that contribute significantly to its storytelling. The most literal loop is Max’s power to rewind time, allowing players to redo interactions with newfound insights, constituting a narrative tool that deepens the exploration of doubt and consequence.

A less literal loop involves the repeated structure of being assigned a task, which generally involves needing to find some object and bring it to a specific location. This motivates exploration of certain areas while trying to solve the mini-mission. It also results in the players interacting with a multitude of objects that don’t directly influence the immediate plot, but which enrich the player’s understanding of the embedded narrative.

For example, when exploring Chloe’s room trying to find a CD to play, I learned a lot of small details about how Max and Chloe grew up together. Through childhood drawings, postcards, and wall markings I got a better sense of how these two used to be with each other. This was immediately contrasted with how Chloe is now, with her new edgy aesthetic revealed through her clothing, photos, etc. If I wasn’t assigned the task of finding a CD, I wouldn’t have explored the room as thoroughly as I did.

While this can be a benefit as it can function to draw the player into the rich, thoroughly thought-out world of “Life Is Strange,” I think it is also the game’s biggest weakness. I found the abundance of interactive elements to sometimes be overwhelming. There is so much redundancy in what you discover from each of the different artifacts that it becomes boring, and feels like it distracts from the narrative. To enhance the experience, the types of indications for especially plot relevant artifacts and complementary world building artifacts could be differentiated. This could help maintain the balance between exploration and narrative clarity, ensuring that players remain engaged without feeling lost in the minutiae. To maintain the motivation for exploration, these differentiated indicators could emerge only after a few minutes of searching.