Artist’s Statement:

We designed Don’t Touch My Recipe! to create an engaging experience that blends together challenge, competition, and fellowship for friends, family, and strangers. In this game, players either take on the role of a chef protecting their secret recipe or a rival investigator attempting to uncover that recipe’s ingredients. We wanted to create a fairly challenging and thought-provoking game that gave people the opportunity to do everything to outwit each other while fostering a sense of friendly rivalry. Our targeted audience is groups of 5-6 people of ages 8+ who enjoy playing logical reasoning games.

We believe that the thrill of balancing challenge and fellowship—more specifically, playing along with and outsmarting opponents—can be a significant driver of fun in a game. Consequently, we incorporated mechanics that encouraged players to employ strategic questioning, bluffing, and logical reasoning. For instance, the game features a system where the Chef selects ingredient cards to mislead the Investigators, and the investigators must ask probing questions and analyze responses to deduce the recipe’s components. To promote a sense of camaraderie and player interaction, we established set communication between the Chef and each Investigator as well as among the Investigators themselves.

Ultimately, Don’t Touch My Recipe! was created to spark friendly competition between the Chef and the Investigators, foster collaboration among the Investigators, and inspire the players to be their most clever selves.

Rule Explanation:

Concept Map:

Our game shape:

Our game focuses on fellowship and challenges. Our game involves a unilateral competition to create fellowship among 5 players, with challenges originating from sabotaging, deduction, and reasoning.

The main objectives of our game for the two roles:

The formal elements of our game:

Initial Decisions about Formal Elements and Values:

When we first started brainstorming ideas for “Don’t Touch My Recipe!”, we knew that we wanted to create a game that would be challenging and fun. We were inspired by games like Werewolf and Mafia, where players are constantly communicating, debating, and trying to deduce each other’s hidden roles. We wanted to capture that same sense of social dynamism and deduction, but with a fresh theme and set of mechanics.

At the same time, we were drawn to the idea of a cooking competition as a premise. We loved the idea of players taking on roles of chefs in a high-stakes culinary showdown, just like in an episode of Top Chef or Chopped. We felt this theme would be relatable and engaging for a wide range of players and would provide a rich space for strategic gameplay and creative expression.

With these initial goals and themes in mind, we started to flesh out the core elements and mechanics of the game:

- The Odd-Person-Out / Saboteur: We wanted to create a game where players (the Regular Chefs) worked together towards a common objective, but with one player (the Saboteur) secretly trying to undermine the group’s efforts. We also introduced a “Judge” role to evaluate the dishes and try to identify the Saboteur. Essentially, we wanted to leverage this idea of hidden roles to create a sense of tension and uncertainty, encouraging players to closely observe each other’s actions and engage in deductive reasoning.

- Ingredients and Recipes: To represent the cooking process, we introduced the idea of using Ingredient Cards that players would combine to create their dishes. Each card would represent a specific component of a set of given recipes, and players would need to cleverly help or mislead the judge (depending on their role) to win the game. We felt that, for a cooking-themed game, it was essential to actually allow players to create a dish in each round, giving them a sense of creative agency and pushing them to become invested in the premise.

- Rotating Turns and Contributions: We wanted the gameplay to feel dynamic and inclusive, with all players actively involved throughout the game. To achieve this, we designed a turn structure where players would take turns contributing Ingredient Cards to a communal dish. This would create a sense of shared ownership over the dish, while also allowing the Saboteur opportunities to subtly influence the outcome. By having the turns rotate around the table, we ensured that all players would have equal ability to participate and shape the direction of the game.

- Judging: To create a sense of challenge and reward strategic play (as well as again going back to the original premise of cooking competitions), we also wanted to create a phase where a player would analyze the dish created by the other players. This idea manifested as the Judge, or someone who would evaluate the dish and try to determine its identity. The Judge role was intended to give players a clear goal to work towards (i.e., provide specifically non-ambiguous or ambiguous ingredients to either help or mislead the Judge) and create dramatic moments of Saboteur reveals as well as the Judge correctly guessing the recipe.

With these core elements in place, our initial prototype of the game was as follows:

- Players: We initially designed the game for 5 players, each randomly assigned one of the three roles: Chef, Saboteur, or Judge. We chose to start with 5 players to balance the time constraints of a turn-based mechanic with the need for having enough Chefs to prevent the Saboteur from being easily spotted by the Judge. With three Chefs, one Saboteur, and one Judge, we felt that we had struck the right balance between game length and deductive challenge.

- Objectives & Outcomes: In this prototype, each role had a specific objective. The Chefs aim to select Ingredient Cards that matched the randomly selected Recipe, helping the Judge to identify the correct dish. The Saboteur Chef, on the other hand, tries to mislead the Judge by selecting deceptive ingredients that didn’t match the Recipe. The Judge’s objective was to deduce the intended Recipe and identify the Saboteur based on the final set of Ingredient Cards. With regards to outcomes, the Chefs and the Judge win if the Judge correctly deduces the Recipe or the identity of the Saboteur, with the Saboteur winning otherwise.

- Procedures and Rules: The Chefs, Saboteur, and Judge are selected by giving each Player a designed Role Card. After the Judge reveals themselves, the Chef and the Saboteur are given a secret Recipe Card. The game then adopts the turn-based mechanic wherein each of the Chefs and Saboteur then select and present one Ingredient Card to everyone else in an attempt to fulfill their respective objectives, starting with the player to the left of the Judge. After each non-Judge player has shown their Ingredient Card, the game enters the judging phase. The game ends once the Judge has attempted to guess the Recipe and the Saboteur.

- Game Platform: A deck of Ingredient Cards, a list of Recipes, and Role Cards.

Testing and Iteration History:

Iterations of Gameplay:

After developing the first prototype of “Don’t Touch My Recipe!” (which at the time was called “What’s for Dinner?”), we began playtesting. Over the course of the past several weeks, we conducted 5 official playtests with external players, including our friends, classmates, and course assistants.

Iteration 1:

Playtest 1, 2: Chefs vs. Saboteur and Judge (Unilateral Competition):

In this initial version, the game had three roles: Chefs, one Saboteur, and one Judge. The Chefs and Saboteur would see a randomly selected Recipe and each of them would select an Ingredient Card, with the Chefs trying to select ingredients that matched the Recipe and the Saboteur attempting to mislead the Judge with their selected ingredient. The Chefs and Judge would win if the Judge guessed correctly, while the Saboteur would win if the Judge guessed incorrectly and couldn’t identify the Saboteur.

We designed this iteration to create an engaging tension between the Chefs, the Saboteur, and the Judge. The mechanics of placing ingredient cards aimed to generate dynamics of bluffing and deduction, ultimately leading to moments of surprise, conversation, and laughter when the Judge revealed their guess and the Saboteur’s identity.

What Worked:

- The concept of hidden roles (Chefs, Saboteur) created a great sense of tension. Players were constantly thinking about the best ingredients to play, as shown by how everyone waited in anticipation for the next ingredient to be put into play.

- The Judge’s role as the guesser created anticipation and excitement for the reveal. Whenever the judging phase began, players’ body languages shifted and the majority of them leaned forward. Players also reacted with laughter or groans depending on whether the Judge’s final guess was correct.

What Didn’t Work:

- The Saboteur had a very low chance of winning by misleading the Judge due to the limited Recipe and Ingredient Card options, resulting in an unsatisfying experience for the player in that role.

- The lack of communication between the Chefs and Saboteur prevented players from engaging in social deduction and bluffing, which undermined the intended aesthetics of challenge and fellowship.

- The quick pace and lack of depth in the gameplay made the experience feel shallow and unengaging, failing to create a sense of investment or fun for the players.

“I loved the suspense of not knowing who the Saboteur was, but the game dragged on too long.” — Anonymous Player

“I felt like there were too many moments of awkward silence whenever the Chefs were selecting their Ingredient Cards, with the only real communication happening when the Judge was trying to guess the Saboteur.” — Anonymous Player

(An in-class playtest on 4/16/24. After this playtest, we fundamentally changed our rules while maintaining our cooking-themed premise.)

Iteration 2:

Playtest 3: Chefs vs. Investigator vs. Investigator (Multilateral Competition)

To address the lack of communication and engagement from players, we fundamentally restructured the game to encourage more social interaction and strategic decision-making. More specifically, we introduced the roles of one Chef and multiple Investigators. In this version, the Chef would randomly select a Recipe from a given list of Recipes and put out four Ingredient Cards, which would be a mix of correct and misleading Ingredients. Each Investigator would then ask any question they wanted about the selected Ingredients, with the Chef having the option to lie or tell the truth in their responses. The Investigators would then each write what they thought was the Recipe.

This significant shift in game design was driven by several key considerations:

- Encouraging active player participation: By giving each Investigator the opportunity to ask a direct question, we aimed to promote engagement and create a sense of agency. This forced conversation to flow between the Investigators and the Chef, whereas in the previous iteration, the Chefs, Saboteur, and Judge had the option of not talking to each other.

- Introducing strategic decision-making: The Chef’s ability to choose between lying and telling the truth added a new layer of strategic complexity. This mechanic required the Chef to carefully consider their responses, balancing the need to mislead the Investigators with the risk of being caught in a lie. Similarly, Investigators had to weigh the information gained from each question and make informed judgements about the Chef’s credibility.

- Creating a more balanced and nuanced game state: By putting the Chef in the position to choose any mix of correct and misleading ingredients, we aimed to create a more even playing field for the “odd-person-out.” This change addressed the imbalance between the Chefs and Investigators in the previous iteration.

What Worked:

- The questioning mechanic sparked more lively discussions, with players actively thinking about which questions to ask and sharing their theories on what Recipes could be eliminated as possibilities.

- The Chef’s ability to deceive led to moments of laughter and visible shock when they answered a question unexpectedly. For example, during our playtest, an Investigator asked the Chef, “Is your Recipe a Beef Burrito?”, and the Chef, without any hesitation, responded “Yes.” Everyone immediately started talking about whether the Chef was telling the truth or not. Although this technically wasn’t a legal question, we wanted to maintain these types of bombshell interactions.

What Didn’t Work:

- Investigators often easily deduced the recipe by process of elimination and because there were no restrictions on the questions being asked.

- There was a disconnect between the mechanics and the premise of the game, with players commenting that the game felt more like a generic deduction game rather than a cooking-themed experience.

- Players would not like taking on the Chef role because there was no incentive to do so. Even if they won as the Chef, there was no tangible reward beyond what they would receive for winning as the Investigator, despite the Chef role requiring more effort and participation.

“There are only two Recipes this could be.” — Anonymous Player

“As a visual person, I wish I could look at all of the Recipes at once and see little cute food icons.” — Anonymous Player

(An in-class playtest on 4/18/22. This was the first playtest of the Chefs vs. Investigator vs. Investigator game. Using feedback from this playtest, we attempted to balance the game for both the Chefs and the Investigators.)

Iteration 3:

Playtest 4: Chefs vs. Investigators with Expanded Recipes and Point System

Despite our attempt to add an engaging strategic element to the game in our previous iteration, the deduction aspect of What’s For Dinner was still too simple. In response to this critique, we increased the number of Recipes to 13 and kept the same number of Ingredients to make sure that the Chef had a better chance of deceiving the Investigators.

To provide an easy-to-look-at unified reference point, we also added the first version of the Recipe Card, where players could clearly show the four Ingredients that made up each Recipe.

Additionally, to make the Chef role more desirable, we made two changes. First, we made the game longer by making it end after every player had taken on the Chef role once (previously, the game was composed of only one question-and-answering phase). Second, we added a Point system where the player with the most points at the end of the game would win. More specifically, Chefs were rewarded with 2 Points if none of the Investigators guessed the Recipe correctly whereas Investigators were only rewarded with 1 Point if they guessed correctly.

What Worked:

- The increase in Recipes led to more engaging discussions, with players carefully considering each ingredient and its potential implications. There were a lot more “a-ha!” moments where players would finally piece together the clues and narrow the list of possible Recipes from 13 to 3.

- The Point System emphasized the balance of challenge and fellowship, with Investigators working together to ask good questions but using separate deductive processes to come up with their own Recipe guesses. When the Chef revealed their selected Recipe, players were wincing or smiling when they realized they had guessed incorrectly or had outwitted the other Investigators, respectively.

- The thought processes of both Chefs and the Investigators became more thoughtful and deliberate, with players using the Recipe Card (which was essentially a laminated whiteboard) to cross out Recipes and write notes. As a result, they were more engaged throughout the deduction process.

What Didn’t Work:

- The Chef’s ability to give any combination of ingredients—both ingredients that were and were not part of their selected Recipe—led to some frustration among the Investigators, as it made the deception too challenging. Essentially, we had overcorrected when trying to make the Chef’s role easier.

(Recipe Menu evolution from original to final version)

Iteration 4:

Playtest 5: Chefs vs. Investigators with Restricted Lying

In this iteration, we restricted the Chef’s ability to deceive by allowing them to give only two misleading ingredients and two incorrect ones. We also limited the Chef to lying twice and telling the truth twice when answering the four questions asked by each Investigator. To complement this change, we created 2 Truth and 2 Lie Cards that the Chef had to play face-down when responding to an Investigator’s question. At the end of the questioning-and-answering phase, the Chef had to flip over one of the Truth & Lie Cards and tell the Investigators which question they had lied or told the truth for.

We also made the Recipe Table bigger and more intuitive by using stylized images of the Ingredients instead of checkmarks and removing the names of the Ingredients in each Recipe. We also added a Divider for the Chef to use so that they could use the Recipe Card when deciding which Ingredient Cards to select so that the Investigators could not see their thought process.

What Worked:

- Smoothest gameplay yet, with players reacting with laughter, surprise, and mock outrage at being misled by other Investigators and the Chef.

- Investigators expressed satisfaction at the more balanced gameplay, as shown by comments like “This round went much better.”

- The improved aesthetic elements enhanced immersion. Players intuitively understood the use of the Recipe Table and relied on it heavily for their deduction processes.

What Didn’t Work:

- Although Investigators who were already close to each other had no problem working together and trying to outwit each other verbally, strangers still struggled to connect and collaborate.

- The game’s mechanics and dynamics did not fully support the intended fellowship-based experience, as players were focusing more on their individual roles and strategies rather than enjoying the shared experience.

(The Chef uses the Divider to devise their Ingredient selection strategy.)

(The Chef uses the Divider to devise their Ingredient selection strategy.)

Iteration 5:

Post 5th Playtest: Chefs vs. Investigators (Unilateral Competition):

To address the lack of social cohesion, we introduced team-based gameplay by requiring the Investigators to work together as a team in each round. They were given discussion phases where they could collaborate to come up with four questions to ask the Chef and one collective guess for the final recipe. If they guessed correctly, each Investigator would get 1 Point, otherwise, the Chef would receive 2 Points. Our intent in adding this mechanic was to encourage more communication between the Investigators and contribute to the game’s aesthetic of fellowship, thereby making the game more fun through increased social interaction (i.e., laughing over creative questions and answers, debating over the correct questions to ask, etc.). This iteration was playtested among our team members.

- The gameplay remained smooth, but this time, we noticed an increase in spontaneous talking.

- There was more motivation for how to strategize and interact with other players.

- There was still balancing issues between the Chef and the Investigators, but the gameplay resulted in wins and losses for both teams.

Overall Takeaways:

We spent most of our effort on improving the challenge and competition aspects of the game in an effort to create a more engaging and balanced experience for players. However, we recognize that fostering a sense of fellowship and encouraging communication among all players is equally crucial to the game’s success. We thoroughly believe that the introduction of the team-based gameplay, where Investigators work together to deduce the secret recipe, is a promising step towards promoting collaboration and social interaction. By requiring Investigators to discuss their findings, share ideas, and reach a consensus, we anticipate that this mechanic will create a more socially engaging experience. This is evidenced by how our game reached a good balance between challenge and fellowship when played by people who already knew each other well. By creating communication channels that the players must use, we would be able to recreate this balance among strangers as well.

Iterations of Visual Design:

Cards: We started with low-fidelity handwritten write/draw-on index cards

- We changed the recipe cards from hand written to printed and laminated cards for the final polished version with better durability.

- We changed the ingredient cards from handwritten to typed and laminated cards for better readability and durability. For the final print-and-play version, we added an icon in the top left corner of the recipe card so that the chef can easily recognize each card when holding them together in hand.

- Chef’s Role Card: We started with the hand-drawn one for prototyping.

- To be cohesive with other cards for the polished version, we drew, printed, and laminated the digital chef’s role card.

- Point Cards: We started with manually recording the points for each player

- To make the game easier to play without a moderator taking notes on the points, we created point cards, which can also be replaced by actual coins in the print-and-play version.

- Chef’s Truth and Lie Card: We added the Truth and Lie cards in iteration 4 for the chef to record his decisions and reveal one of the cards after the questioning stage. Doing so, we add limitations to the chef to balance the difficulties of the two roles, which increases the fun challenge for everyone, especially for the chef.

-

Recipe Menu: We started with the handwritten menu list for iteration 2.

- We incorporated the takeaway that a single menu list makes it hard to compare recipes. Following the design principles, we built a table instead of a compact list to make the recipes more readable for each player. We also laminated the menu so that the players take notes, such as crossing out the incorrect recipes.

- During iteration 4, we received feedback that the checkmarks were distracting and the ingredient list on the left was unuseful. Therefore, we removed the left ingredient list and replaced the check marks with the ingredient icons for clearer visual representation.

Rule book: We started with no hard copy and relied on the moderator to explain the rule all the time for iterations 1 to 3.

- During iteration 4, we organized the rules and printed them out.

- Following the feedback that the rule book was not organized well, and following the design for the rulebook, we re-organized the rules to create a booklet-style rulebook with contents in a more logical order

- After our final playtest, we add additional images referencing the game contents in our third version of the rulebook to help match the cards and descriptions, as well as the background color and icon to be cohesive with the design style of other elements.

- Finally, to make the rulebook more readable, we removed redundant texts to make a less text-heavy rulebook with visual images for our final rulebook (with images in the design mockups below).

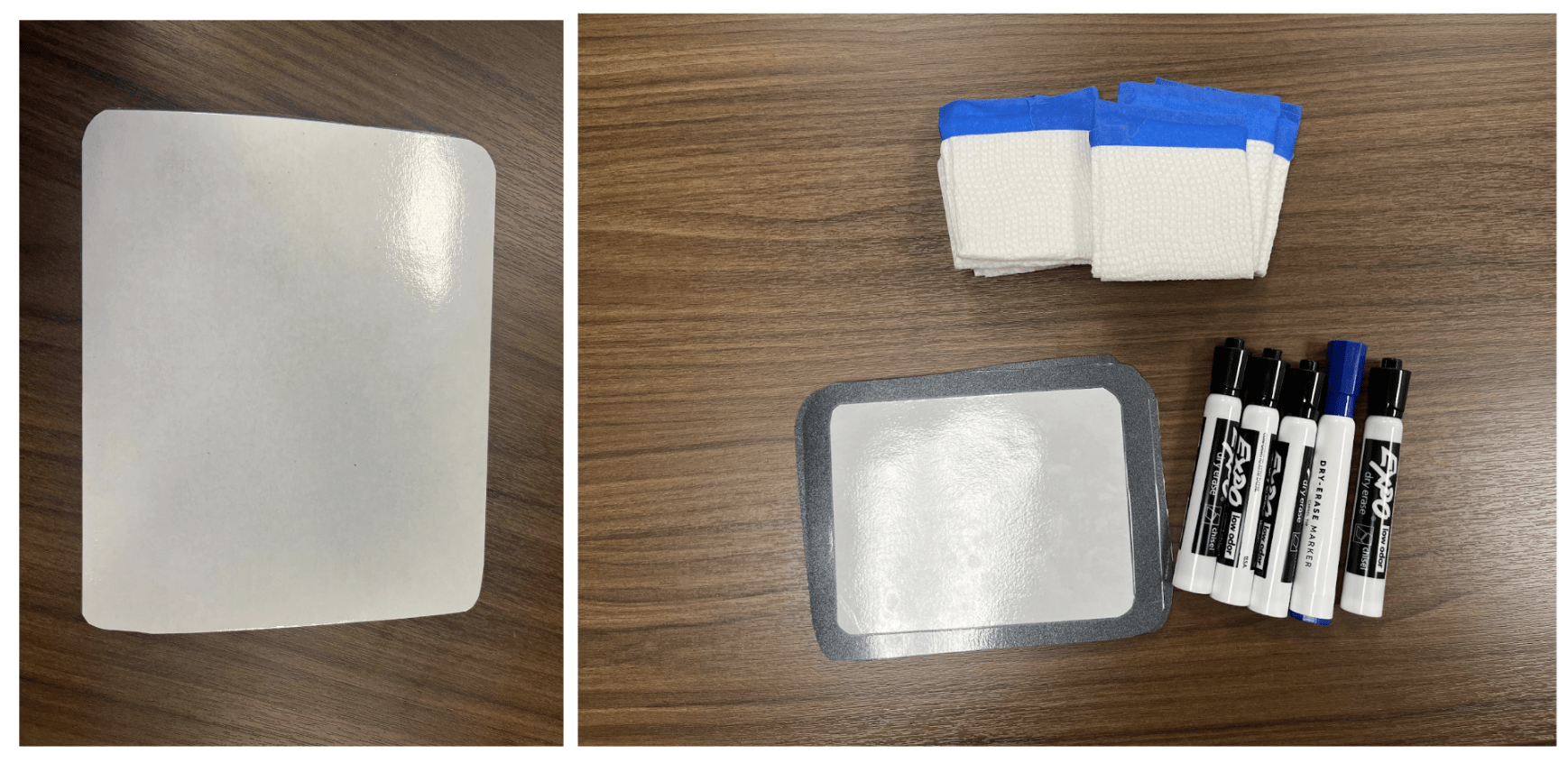

Whiteboard, markers, and erasers: To fit in with our new game mechanics where investigators need to write down their guesses and show them together, and also to provide space to take notes, we added those resources.

- We started with a single laminated paper but realized during our iteration 4 that the paper is too thin so the marks could be easily recognized from the back side.

- Therefore, we adhered the black and thick paper to the back of the whiteboards in our final physical version.

Front and back of the box: Due to the time limitation, In our physical version of the box, we used AI-generated images for the front and back of the box as an illustration as we focused on the game mechanics first.

- After our final playtest, we draw the images for the front and back of the box to be cohesive with the styles of other materials to follow the design principle of unity. We remove redundant texts on the back to not distract attention.

- Finally, to further reduce the text density of the back of the box and make our main contexts clearer, we removed more text from the back of the box. The design of our final version of the box is in the design mockups below.

Final Prototype:

Physical Version:

Whole Bundle:

Here are the contents of our game box:

Print-n-play Version:

- Recipe menu

- Recipe cards

- Point cards

- Ingredient cards

- Chef’s cards

- Additional materials

- Rulebook

- If you prefer a booklet version of our rule book, you can print this document out, double-sided.

Our Design Mockups:

Box:

Cards:

Point Card:

Ingredient & Recipe Cards:

Chef’s Cards:

Recipe Menu:

Rulebook:

.

.