Artist’s Statement

Pizza Pizzaz is an exciting card game designed for 2-6 players aged 10 and up. This game casts players as competitive pizza chefs battling in the ultimate culinary showdown. The core of the gameplay revolves around drawing ingredients, placing toppings, serving hungry customers, and stealing from rivals to assemble the most mouth watering pizzas. Our intention was to enhance competition— or “anti-fellowship“—by encouraging players to engage in light-hearted rivalry and fast-paced play. Additionally, the game fosters creativity and self-expression, as each player has the freedom to build their unique pizza creations. We aimed to create a game that not only brings people together for a fun-filled pizza making challenge but also offers a slice of escapism where players can immerse themselves in the bustling atmosphere of a pizzeria. Through a blend of strategy, social interaction, and competitiveness, Pizza Pizzaz offers an engaging and dynamic experience for families and friends looking for a lively and interactive culinary-themed game!

Initial decisions about formal elements and values of your game

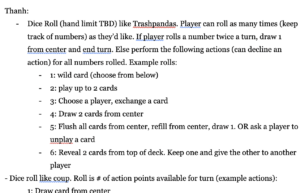

Pizza Pizzazz was born as a standard deck-builder during our in-class brainstorming session. With only a title and the notion of card collecting, we set out to create the foundation of our game, beginning with independent ideation. We knew we wanted to create a game that revolved around collecting pizza ingredients and awarding players points based on their chosen ingredients. The four of us created very small sample games that shared many characteristics and were unique in other respects. Some ideas revolved around using money to purchase ingredients, and others had players collectively working on building shared pizzas.

We noted each game’s salient mechanics and used a heat map to decide which would make it into our initial prototype. Each group member put dots of their chosen colors on the mechanics they were most excited about.

Our initial mechanics boiled down to:

- Recipes that players had to compete to complete

- Players build their pizzas by stacking ingredients in front of them

- Using the dice mechanic from Trash Pandas to give players different actions on their turn

With these mechanics, we hoped to create a deck-builder game that allowed for complex social dynamics, such as players sabotaging each other’s pizzas, stealing orders from other players, and taking ingredients from others’ pizzas. Our goal was to get players energized and engaged with each other as they fought to serve customers the best pizzas they could build. For our initial playtest, we aimed to create a stable foundation upon which our game could be built.

Testing & Iteration History

Iteration 1: Building the Basics

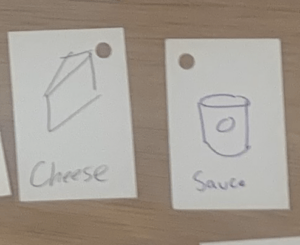

The first iteration of Pizza Pizzazz consisted of ripped-up sheets of paper, each depicting one of four pizza ingredients: cheese, sauce, meat, and veggies.

The first iteration of Pizza Pizzazz consisted of ripped-up sheets of paper, each depicting one of four pizza ingredients: cheese, sauce, meat, and veggies. Players would stack different arrangements of these ingredients in front of them to fulfill customer orders, which would vary in how the ingredients were arranged. Players would take actions like placing ingredients, drawing cards, and interacting with other players through actions they could earn by rolling different sides of a single dice. If they rolled the same face twice, their actions would be forfeited, and the next player would take their turn. This was a nearly 1:1 modification of Trash Panda’s dice mechanic.

The simplicity was purposeful. We wanted to build a solid foundation of cards and mechanics that would allow players to manage resources while having simple interactions through a single die so that we could have a solid, simple foundation we could build from as the game grew. As we walked into our first playtest, our main goal was to determine if our established procedures could operate toward a conclusion while staying free of game-breaking exploits or obstacles. With our first playtest with strangers, we explored the following themes:

Basic Pizza Building

In their most basic form, do our rules form a cohesive, achievable goal for each player to pursue without encountering any game-breaking obstacles or exploits?

Successes

Our first playtest went excellently. The strangers playing the game successfully managed their resources and built pizzas, rarely getting stuck. This was the first stress test for every moving part of Pizza Pizzazz, and it largely accomplished everything we needed it to. Several customers were served, and every player collected points by the end of the playtest. One of our players commented on this, saying the game “was a bit confusing at first,” but once they had passed three rounds, they “got the hang of it pretty quickly.”

Failures

However, there was room for improvement. In its first iteration, playtesters commented that the game was “relaxing,” as they could build pizzas and collect cards. While it was meant as a compliment, this comment alerted us that our simplicity in ingredients and pizza building may have made our game’s primary form of fun submission as opposed to fellowship, seeing as most players were too focused on their own pizzas to interact with others. Most of our playtesters expressed a desire to “steal cards from other players.” For our next playtest, we would explore ways to encourage more player interactions and social dynamics without relying on increasing the complexity of the die.

Die Mechanic

Would the dice mechanic introduce enough opportunities for the players to interact? Would a little chaos make the game more engaging for players?

Successes

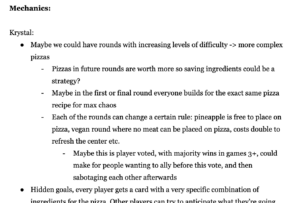

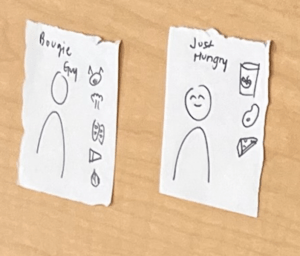

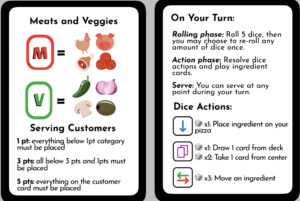

Our dice functioned as a modification of the die in Trash Panda, with each face representing a different effect. Players would roll to get as many actions as possible until they were satisfied, but if they rolled the same face twice, they would lose their actions. Our possible actions for this iteration are outlined in the picture on the RIGHT.

Players engaged heavily with dice, confirming our theory that players would enjoy the randomness and chaos of a dice roll. Because players were essentially gambling to earn more actions, the stakes were raised with each reroll, making each success after the first roll feel like a reward. One player described “trying to get all of the actions in one turn so [they could] go again.” Because players were new to the game, finding every action was a key motivation, as players interacted with the portions of the game they hadn’t learned from yet, according to “What Games Are.”

Failures

Because players could not make any pizza progress by “busting,” it was demoralizing, but they also felt they could not progress without taking risks, many of which did not pay off. The multiple rolls of a single dice and the resolving of potentially six different actions afterward slowed down player turns considerably as they spent over a minute in some cases deciding what order to take their actions in to be optimal. Several effects were too powerful to occur on every turn, and the sheer number of potential actions was complicating the game beyond pizza building. EXAMPLE Players “couldn’t roll without looking at the reference sheet,” leading to a playtest with players stuck to the rulebook even after multiple turns. Before our next playtest, we would brainstorm a new way to tie action-taking to the randomness of a dice roll but give the player enough agency to do more on their turns and aim for actions they want to take. We would go on to experiment with another die mechanic for our next prototype, opting for a simpler version that allowed for less complex actions but still encouraged player interaction.

Unexpected Issue: Stacking Ingredients

Making it so that players had to stack their ingredients in a specific order was our attempt to introduce structure to the game. This idea worked in theory, but in practice, the gameplay was slowed down considerably, as people with over ten cards still didn’t have the necessary cards to continue building a stack. For the next playtest, we kept ingredient requirements but eliminated the stacking component, instead allowing players to place and take cards in any order, thus making the option to build your pizza as attractive as sabotaging someone else’s. This would ideally create enhanced social dynamics, where every player has much more freedom to place ingredients, allowing for a faster rate of served pizzas and more chances for other players to interact with their peers by stealing, moving, and adding ingredients.

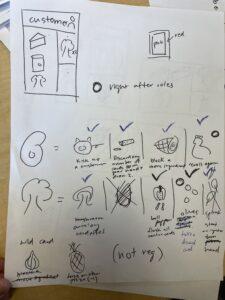

Iteration 2: Reimagining Player Actions

We entered our next iteration intending to involve the players in the game further, which meant giving them more actions and choices about how to take them. This would ultimately fulfill their psychogenic need for autonomy as players. We replaced the Trash Pandas dice mechanic, opting for three die faces with simple, easy-to-remember effects. Players would roll four dice simultaneously, choose which face to keep, and reroll the rest. At the end of their rolling, they could perform actions as outlined in our sketch. This would keep the gambling aspect that kept players rolling with the previous dice mechanic, and the guaranteed four actions would give players more opportunities to do something on their turn, even if they rolled suboptimally. These different dice faces were enough to satisfy most player profiles, as achievers, explorers, and socializers could each find enjoyment in placing ingredients, drawing cards, or moving other players’ ingredients, respectively. Simplifying dice actions to three core mechanics would also push players to place ingredients and draw cards at roughly triple the rate, increasing the game’s speed.

To maintain some of the chaos of the powerful actions we removed from the last iteration, we created our first cards with special effects, introducing them as limited ways to severely impact other players while keeping stronger effects tied to rare cards, as opposed to actions that could happen on every turn like the previous iteration. People with “killer” player profiles and socializers would particularly enjoy this change, as they still had opportunities to affect other players. This would ideally introduce some balance to the social dynamics, such as stealing cards from other players to build one’s pizza

Additionally, we removed stacking entirely, choosing to go with our backup option: allowing players to place pizza ingredients in any order. If they submitted the right collection of ingredients, they would earn points. The hope with this choice was to make getting “stuck” because a specific ingredient was missing much rarer, increasing autonomy in the process. For our next playtest with strangers, we gave them this iteration, hoping to gain some insight into the effects of these changes.

New Dice Mechanic

Does the modified dice mechanic speed the game up? Is it easier to understand than the previous one?

Successes

Players quickly picked up the new dice mechanic, finding it “easy to understand once you do it once.” As a result of this increased learnability and simplified approach to dice rolling, the game moved much faster as players quickly learned which dice they wanted to prioritize rolling for. One player commented on how excited they were to reroll their dice, stating, “Even if I didn’t get what I wanted the first time, I still had a chance to reroll the dice I didn’t want.” This, combined with the helplessness that came with busting, proved that we had increased player autonomy while significantly simplifying the game’s rolling mechanic.

The game’s pace also notably increased as players took many more actions on their turns. In the 15-minute prototype, every player served at least one customer.

Failures

Despite the successes of the new dice, players were still very attached to the reference page. Every player used it to organize their rolled dice to determine which actions they could take. We noted this, feeling that a cheat sheet should be a permanent addition, given how naturally players gravitated toward it.

Despite the increased pace, there would be rounds where every player drew cards. Players often shrugged when they saw a disappointing dice roll, taking their cards from the center and accepting that they could place no ingredients on their turn. An increased pace still left players feeling like they didn’t have enough to do on their turn. We took a simple approach to this problem: increase the number of dice one can roll on their turn. This would increase the pace a little more while giving the players more to do on their turns.

Special Effect Cards

Does including the special cards increase interaction between players?

Successes

The special effect cards did have players interacting more frequently and allowed them to make choices about how they would use certain resources. Our playtesters had to determine if “it was better to serve a customer that wanted the jalapeño or use it to steal someone’s card,” which introduced some complexity to players’ turns. Players still mainly interacted through the Move Ingredient action on the dice, but the new card effects forced them to strategize about “how to get [their] pizza done before [the other players] ruin it.”

Failures

However, because they were so rare, every player had an average of one or two special cards. This meant that players spent most of their game holding onto these cards, feeling that their scarcity forced them to wait for the “right time” to use their effects. Because our goal was to get players to enjoy fellowship and to meet the psychogenic need for power, we noted that a higher frequency of special effect cards would encourage players to use their effects frequently, even if the timing wasn’t perfect. By changing this for the next iteration, we hoped players would thus hopefully use more special effects to create social tension and rivalries at the table.

No More Stacks

Does eliminating stacking make the game move faster?

Successes

Eliminating a forced order of ingredients did have players placing their available cards down as soon as they could. This meant that the number of cards on the table had increased significantly, allowing for exciting dynamics to arise as players tried to outplay each other with their pizzas. One of our playtesters relied on looking at others’ placed cards to avoid going for the same customer as them. Another frequently taunted other players, telling them he was “coming for [their] pizza next.” By reducing restrictions on gameplay, players naturally found more instances to interact with each other. We managed to preserve the challenge of collecting every ingredient while keeping the aesthetic of building a good pizza with the right ingredients. This also significantly sped up the game as players no longer had to wait for a single ingredient.

Failures

As more cards were placed, players wanted to use the ingredient arrangements of their opponents to their advantage, whether to collect information or steal cards. However, eliminating the stacking structure meant that each player would arrange the cards in whatever seemed most intuitive. One player stacked all the cards directly on top of each other, blocking other players from seeing everything but their top ingredient. Another playtester neatly laid out their cards so they could see their own pizza better. However, as more cards entered the playing area, “What cards do you have down?” became a frequent question. To address this issue, we considered directing players to place their cards uniformly to decrease the friction that came with card-based fellowship. Giving players placemats as an organizational tool thus became a priority for the next iteration.

Unexpected Issue: Unclear Customer Cards

As we conducted our playtest, we found that the customer cards were too small, given their purpose of being visible to the whole table. They were too visually similar to the ingredient cards, and as players passed them around, they quickly became lost or mixed up with other cards as players had nowhere else to place them. To fix this issue, we wanted to increase the size of the customer cards to make them (1) stand out from ingredients and (2) be visible from any part of the table without being picked up.

Iteration 3: Giving Ingredients Power

For our third iteration, we playtested the game ourselves because changing most of the cards in the game required patience from the playtesters. We liked the direction the special effects like the jalapeño, which increased the frequency of social interaction between players. By offering new effects on almost every card in the game, we hope to accomplish two major goals: (1) introduce more unpredictability and (2) make players interact, whether they are being hindered or helped.

We also introduced a low-fidelity placemat to encourage players to spread out their cards. Including the placemat was an attempt to improve the organization of the pizza-building mechanic—the mats would offer structure, showing players how to arrange their cards. In this playtest, which consisted of smaller modifications, we also played around with the amount of dice available to roll. We wanted to speed up the game but didn’t want to overburden players by giving them too much to do on their turn.

Increased Special Effect Frequency

Does injecting plenty of abilities increase the social interaction between players? Does it make drawing cards more exciting by introducing value?

Successes

Introducing card effects to almost every single card in the game increased the unpredictability of the game considerably. Players interacted much more by stealing from each other, using card effects to sabotage other players, and bluffing to protect their cards. As a player, Francis was about to serve a customer for the maximum number of points. Other players formed a temporary alliance to kick out the customer before Francis could serve the pizza, rendering his creation useless. When one player finally managed to use an ability to make the customer leave despite their order being nearly done, the attempt was quickly blocked by Francis’s mushroom, which negates a card effect.

These kinds of interactions became common as cards allowed players to band together against other players or protect themselves. Fellowship had taken the spotlight as the primary source of fun, and an interesting second effect was discovered. Once another player, Thanh, was in an obvious lead, she asked, “Should I just start trolling?” our game’s accessibility to “killer” player profiles with a psychogenic need for power. If someone wanted to spend the game only sabotaging other players, they could do so at the cost of their success.

Failures

No significant failures related to the special effects of the cards came up in this iteration of playtesting. However, we knew that as more playtesting occurred, interesting interactions would arise between different types of cards, so we continued with a watchful eye on any cards that may disrupt the game’s balance or unfairly advantage players who use them.

Dice Count

Does increasing the number of dice speed up the play rate by allowing players to do more on their turn?

Successes

Increasing the number of dice to 6 greatly sped up the game. Players could draw all the necessary cards, place them, and serve a customer all in one turn. As a whole, customers were being served much quicker, and points were acquired much faster. Two extra dice made every action easily acquirable on their turn, and most players took advantage of this to advance in the game.

Failures

While we did achieve our goal of speeding up the pace of the overall game, the downsides far outweighed the positives. The game moved quickly because players could craft pizzas worth the minimum point values on a single turn without other players’ intervention. By increasing the player’s autonomy on their turn, we had inadvertently reduced the challenge of building pizzas against the competition. Some players could craft two-point pizzas on their turn easily, and no one could do anything about it unless they foolishly decided to leave their almost complete pizza undelivered for an extra round.

Players were also making more progress, but the speed of each player’s turn had significantly decreased. Players had to manage six actions on their turn, and the lack of interventions from other players meant that players were silently taking their turns. As a result, other players began using their phones or having conversations amongst themselves. Thus, The magic circle became faint as long turns strained the players’ immersion.

To improve this, we set out to try 5 dice for the next iteration, hoping that this “sweet spot” would give players more autonomy than the 4 dice alternative but would avoid the pitfalls of 6 dice. This, combined with more expensive actions (such as increasing Move Ingredient from a 2 dice requirement to 3) and minimum ingredient requirements for customers, would ideally make players feel they are progressing while giving other players a chance to intervene in their strategies.

Introducing a Mat

Does a placemat encourage players to spread out their cards so other players can easily see their plan? Is its design easy to grasp?

Successes

With the introduction of the placemat, players no longer stacked ingredients in such a way that other players. They naturally laid out their cards so other players could see their placed ingredients. The placemat gave structure to the players since they could visualize how close they and other players were to completing an order. Players could also quietly (and loudly) strategize to sabotage another player as they saw their pizza grow. This facilitated social interactions between players, reducing fiction by skipping the “What cards are on your pizza?” pain point of the last playtest.

Failures

However, there was confusion about how the placemats connected with the customer cards since we only had one slot for the second-tier ingredients on the mat. Most customer cards at the time had two ingredients needed for the second tier. There was a disconnect between the mental model players had of pizzas as the customer cards presented their required ingredients one way, and the placemat arranged them in another. For our next iteration, we wanted to make the placemats more aligned with the customer cards to make the connection between the two natural and the placemat intuitive to use as a result.

Unexpected Issue: Loss Aversion

After Francis had his pizza thoroughly sabotaged because he waited an extra turn to aim for the highest point value, no other player attempted to score beyond the one-point mark unless they were certain they could deliver the pizza on that same turn. We recognized the issue as loss aversion: players had little incentive to go for the higher-value customer cards because they were afraid their placed ingredients would be stolen before their pizza was ready. To combat this, we took a two-pronged approach:

- Increase the rewards for serving customers complex orders from a single extra point per completed tier to double that, with a perfect order earning a player 5 points instead of 3. Players had to consider the risk of having their pizza sabotaged as a worthwhile one.

- Make the Move Ingredient action rarer. With 6 dice and a cost of two faces to move ingredients away from players, players could move up to three ingredients away from their rivals at any point. We reduced the dice count to 5 and increased the requirement to move an ingredient from two faces to three, making it so a player could move, at most, one ingredient away from a player on their turn. Making the main theft ability rarer would make players more confident that their pizza would survive should they build it.

Expected Issue: Standardization of customers

Unsurprisingly, our customer cards were another issue. Because we kept adding customers to our prototype without reviewing the older ones, some customers were too easy to serve, like the one below, who only needed 2 cheeses, the most common ingredient, for 1 point. This made some customers obsolete, as the obvious strategy was to serve the easy ones. Furthermore, the ingredients on the customers were too small, and the customer drawings were too big, making the cards hard to read. For the next iteration, we would redesign the customer card using feedback from our TA, who felt that a horizontal design with the ingredients in clearly divided tiers was the best approach to allow for a sense of visual hierarchy in a familiar format. Increasing the size would also make the card available to every player without forcing them to pick it up to get a better look.

Iteration 4a: Translating for Customers

Our fourth iteration underwent the most changes. With this iteration, we reduced the total dice count to 5 on the hunt for the sweet spot between progress and challenge. We also implemented our two-pronged approach to combat loss aversion by changing the Move Ingredient requirements and increasing the value of complex recipes. Finally, we rolled out our medium fidelity cards, including improved customer cards that centered the ingredients and were large enough to see from across the table. Strangers would playtest this iteration only using the rulebook and occasional clarification from the moderator.

Rulebook

Is our rulebook clear enough for new players to grasp and play successfully? Did improving the fidelity guide players?

Successes

The rulebook was an excellent reference to players who felt they could “take a look at it whenever I wasn’t sure about something.” Players leaned on it for information about permitted interactions, and the several examples in the rulebook of sample turns guided the group as they learned how to play. The “cheat sheet” on the placement, pictured here, allowed players to track their own dice rolls without needing the entire rulebook. The one-line descriptions of the actions aided in recognition over recall and stopped the rulebook from being passed around for that purpose.

Failures

With conversations with our players and teaching team, we found that the rulebook was not as accessible as it should have been. As Krishnan said: “9 pages is a little much.” We knew we had to restructure the rule book in three different ways:

- A trifold would be much easier to reference, as players could see two pages at once instead of having to flip through a stapled packet.

- Sections of the rules must be reorganized to be presented in a certain order, and procedures should be separated from components.

- Players should have more cheat sheets with simplified mechanics to jump into playing faster.

Dice Adjustment

Do 5 dice improve the pacing of the game?

For the first time, the dice mechanic worked exactly as intended, with players having enough action economy to make progress but not so much that they could complete orders in a single turn. For now, the dice can remain untouched.

Encouraging Pizza Building

Will people be more willing to place ingredients with Move Ingredient actions rarer, and pizzas becoming harder to make? Is loss aversion mitigated?

Successes

Our two-pronged approach was a massive success, as players almost exclusively aimed for the higher-value cards despite knowing that their cards could be taken from them if they spent too long building their pizza. One player commented, “Why would I even go for one point when I can get five?” This was before she realized she had put a target on her back with that comment.

Making the Move Ingredient action rarer also improved the game, making players feel more rewarded by the ability when they rolled correctly. The interactions would happen less frequently, but this made them more meaningful. Players who wanted to move ingredients could optimize their dice roll to earn the action, but players were no longer sabotaging others because they unintentionally rolled the requirement.

Failures

Making the Move Ingredient action rarer slightly reduces player autonomy and is a tension point for players. If a player rolled two Move Ingredient faces, they could not use the ability unless they rolled a third. When their attempt failed, players expressed frustration at having wasted two potential actions. However, this point of tension only adds to the game, as not every attempt to sabotage a player with dice is successful. The ability to fail minorly with your roles also increases player investment, as a bad play could result in a consequence that won’t ruin a turn but will put them at a disadvantage.

Customer Card Remodel

Are the new customer cards equally attractive? Will people go for higher point values?

Successes

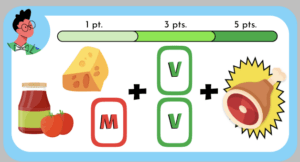

As mentioned, the increased point values made players much less prone to loss aversion in the form of ingredient hoarding as players strived to serve more complex pizzas. The standardization in making every card 5 or 6 ingredients to complete ensured every card was equally attractive unless a player had a specific arrangement of ingredients that encouraged them to serve a particular customer.

The size of the cards and the ingredient logos also made the customer’s cards visually accessible to everyone at the table. None of the players picked up the cards to get a closer look since they could easily see the lineup from any table. Matching the arrangement of the cards on the placemat to the arrangement of the cards was intuitive for players, with one of them saying, “We probably have to put ingredients here [pointing at mat] like that [pointing at a customer card].”

Failures

The customer cards had two major shortcomings that would be quickly addressed for the next iteration.

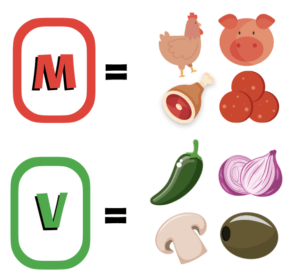

First, we communicated to players on the customer card that a customer like the one below wanted ingredients that fit into the meat and veggie categories. These logos were ridiculously confusing. One player commented, “I didn’t know the broccoli was supposed to mean any green card,” so players would spend the whole game waiting for broccoli or steak ingredients until we clarified for them after realizing no one was making progress. These categories were described in the rulebook, but we should have made it clearer on the customer cards themselves and on a separate small reference sheet.

Our teaching team gave us an example of how we could redesign our customer card to make the collection of points clearer. We settled on the design below, communicating through the card that a customer who awards 5 points needs a jalapeño as well as every ingredient to the left.

Iteration 4b: Getting Players Playing

The primary goal of this playtest iteration was to evaluate the game’s functionality when players solely relied on the rulebook without any additional clarification or explanations from moderators. We wanted this playtest to model a real life game, where people cannot interact with the designers and must refer to the rulebook for any ambiguous situations. This differed from our previous playtest, since we also mirrored real-life playing conditions by having no time constraints to better understand the pace of our game and how long players needed to learn and understand the rulebook. We wanted to see how players interacted once they had a good grasp of the rules, since playtests in class ended just as everyone was starting to understand the game.

We made some minor changes in the game between this and the previous playtest, clarifying the customer cards and making adjustments in the rulebook.

Removing Time Constraints

Will letting players play a full game without time limit or instructions introduce any new problems or insights?

Successes

Players took about 10-15 minutes to familiarize themselves with the rulebook before playing the game. This seemed to help all of the players absorb the game rules at their own pace and avoided the situation where one person explains the rules to everyone else, aligning more with our goal of respecting player agency and choice. The ability of players to all take part in setting up the game and understanding its components without continuous guidance demonstrated the effective learning process. This autonomy ensured that all participants, regardless of their direct interaction with the rulebook, grasped the basic concepts necessary for gameplay, allowing for a sense of competence in the game experience.

Failures

Despite these successes, the game’s pace was slower than anticipated, primarily because there was frequent referencing of the rulebook for minor gameplay details. We also noticed that people went back to their placemats frequently to understand the dice roll actions. Thus, it was reinforced that providing cheat sheets that simplified major game mechanics proved useful and should be expanded to better explain other important aspects of the game like players’ action phases.

Customer Card Clarity

Are the customer cards clear to the players?

Successes

The players had no issues understanding the customer cards in this playtest. Previously, people had issues understanding that the meat and veggie images on the card were generic meat and veggie ingredients. To increase player cognizance and quicker decision making, we incorporated the symbols [V] for vegetables and [M] for meat. This inclusion of clear, easily recognizable icons allowed players to quickly understand what each customer was requesting, demonstrating a significant improvement in their understanding of game mechanics.

Failures

The players were unclear whether the customers should be placed in a discard pile or kept with the person who had served them. Our game rules did not specify where they should be placed. This became important because some people used the “Coupon” card to bring back the last customer they served, requiring clarification that was not offered.

Since there had been a few turns between using the card and someone serving a customer, there was a lot of confusion in determining who was last served. This issue slowed down the gameplay as players debated and limited the use of the “Coupon” card as people were unsure of their options and could not strategize as effectively. This experience highlighted the need for better rule exposition to prevent further confusion. We would clarify each card action on the card itself and in the rulebook.

Social Dynamics

Are players interacting more once they know the game’s rules?

Successes

The extended time led to heightened competition in our playtest. Players were more invested in their pizza creations, and we noticed more intense reactions during gameplay. For example, players exclaimed, “How dare you!” when others interfered with their pizzas. The players would also cheer and clap when their opponent’s pizzas were being messed with, which demonstrates the success of Pizza Pizzaz in the relatedness aspect. Overall, it seemed that players could enjoy the fellowship of Pizza Pizzazz without any major issues in component fidelity or rule clarification that hindered their play.

At this point, we were able to fulfill players’ sense of achievement as they consistently served customers and gained physical point tokens.

Unexpected Issue: Missing Card Counts – Notions of Scarcity

During the playtest session, players encountered a problem regarding ingredient card counts in the deck. They specifically wanted to know the quantities of each type of card, especially the special cards with more powerful abilities. The rulebook at this stage did not contain details on card distribution, forcing players to make strategic decisions based on guesses about the availability of these special cards.

Recognizing the importance of this information, we understood that players’ ability to develop effective strategies depended on knowing the rarity of the cards they held. For example, if a special card is known to be rare, players would be more likely to save it for critical moments, practicing harm avoidance by not wasting valuable resources. Conversely, if they knew such a card was common, they might use it sooner, avoiding the pitfall of withholding resources that could be better utilized immediately (infavoidance).

The absence of this information in the rule book limited the ability of players to strategize effectively, and we noted this area for improvement in our rulebook design.

Unexpected Issue: Unclear card abilities

During the playtest, some players were confused about one of the card abilities. They looked in the rulebook for clarification, but the explanation was still unclear. We found that the rulebook described the card ability in two different sections, which made it hard for players to find the information they needed.

Additionally, our attempt to use thematic wording related to a pizzeria, like “Refuse service to a customer” instead of a simpler “Kick out any customer,” added to the confusion. We noted this issue and planned to make the descriptions clearer in future versions of the game.

Future iterations

- Cheat sheets!

- Fixing rulebook – card counts, card ability descriptions are more clear

- Point tracking – feelings of growth and progress

- Special customers and card balancing

Once we decided to use color as the main differentiator between different card types, we ran into the issue of using red cards for meats and green cards for veggies, considering red-green colorblind individuals would struggle to differentiate between the two types of cards, such as the customer below, who wanted both meats and veggies.

To be more inclusive, we added an M to the center of the meat cards and a V to the center of the vegetable cards, making them easily differentiable to individuals with red-green colorblindness.

Finally, in our reference cards, which every player receives (pictured right), we provide a visual reference that would further aid people who might not be able to tell whether the card they are holding is red or green.

Figma for design drafts: https://www.figma.com/file/W7gmHPQ9OcIk62IhPJ2D0z/Pizza?type=design&node-id=0%3A1&mode=design&t=t5AUaOW2Ilhy1Kmd-1

Final Playtest video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t5CuQKZJqR4