Artists’ Statement

We created Dare to Share as a fun party game to bring people together through the sharing of personal stories and experiences. In today’s world, genuine social connection can sometimes feel elusive. People often present curated versions of themselves, especially online, hiding their flaws, quirks and embarrassing moments.

Our goal with Dare to Share is to create a playful space where people feel comfortable opening up and being vulnerable with friends. By gamifying the sharing of personal stories, from tame everyday mishaps to spicier romantic escapades, we want to normalize talking about the imperfect, messy, hilarious parts of being human. The twist cards add an element of spontaneity and challenge, pushing players to step out of their comfort zones in how they tell their tales. At the same time, we hope to give players a sense of safety. While we do want players to share those more embarrassing moments, we want them to have the choice to do so – hence why we provide a variety of levels, for people who are just meeting for the first time at a party, to close friends who are trying to fill in the last gaps in their knowledge of each other or even just relive shared keystone moments.

Ultimately, we hope Dare to Share leads to lots of laughter, ‘I can’t believe you did that!’ reactions, and most importantly, a sense of bonding and camaraderie among the players. We believe that seeing your friends’ silly, cringeworthy, vulnerable sides, and having them see yours, is a powerful way to feel close to each other. In some small way, maybe this game can break down the barriers we put up and remind us how refreshing it is to let our guards down with the people we care about.

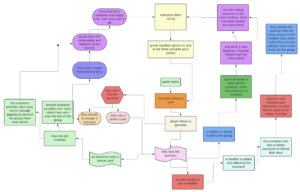

Concept Map

Initial Decisions

When we set out to create Dare to Share, we knew we wanted to design a social party game that would bring people together through laughter and storytelling. Our team’s favorite board game memories came from late nights in dorm rooms, playing games like Cards Against Humanity that got everyone laughing and bonding over shared humor. We wanted to capture that same spirit of casual, social fun while adding a new layer of personal storytelling.

Our major values in the game were to center the game around personal stories and experiences. We felt that sharing real-life anecdotes would foster a sense of authenticity and relatability among players. By encouraging people to open up about their own lives, we hoped to create a space where players could connect over shared experiences and get to know each other on a deeper level, just like those memorable dorm room game nights. We also wanted to center a significant portion of the game around focusing on people’s personalities. While stories in of themselves are fun, we believed the way in which those stories are presented adds a new layer of depth to the story, and the storytelling style often provides a window into the personality of the answerer.

While our game is also inspired to some extent by We’re Not Really Strangers, we felt that we wanted our game to be a little bit spicier and tangible. While We’re Not Really Strangers does a good job of encouraging players to divulge their inner feelings, we believe that telling stories, because they are retellings of concrete (and in many times, recorded!) events, can in many cases make the bonds between players stronger.

Thus, our first mechanical decision was to model the game’s draw mechanic around We’re Not Really Strangers. The mechanic is extremely simple – there are basically just cards in three different levels, that players go around the circle drawing. We incorporated something similar (the initial design only had one level, though we grouped them into three groups for our final design) for ours – we felt that the element of random chance would encourage players to step out of their comfort zone, rather than simply picking easy questions that they could answer while still being completely safe.

Another major mechanic decision was to add modifiers. We wanted the game to feel more dynamic than simply going around the circle and answering questions rapid-fire, so we added a set of modifiers that players could use to make answers more high-stakes or change their delivery. Similarly, these were random, so that players couldn’t simply snipe easy modifiers. However, we also realized that some questions were already very high-stakes or attention-grabbing, and that players that got those questions might not necessarily want to answer with additional difficulty introduced. To avoid this, we made modifiers optional – players had the choice not to take the risk.

To make the game further interesting, and keep players who weren’t answering at the time engaged, we also added action cards (these were, for the most part, not incorporated into the final product. However, remnants of their ideas live on!) We thought that it would be fun to allow players to troll each other or the answerer – sometimes by giving the answerer extra trouble, at other times by reassigning a question to a different person that they knew would have a good story for, etc. We hoped this would keep players from feeling unengaged between or during rounds; however, as we discuss below, this mechanic was almost completely forgotten during the actual playtest.

Finally, we chose to introduce a steal mechanic. Inspired by games like Ryan Higa’s I Dare You YouTube video series, we thought it would be cool to allow more daring players, or players who had a good story to share and who were unafraid to do so, to jump in. We imagined this would prevent a lot of questions from being “dead” – that is, even if the person on deck didn’t have a good answer, someone else might. We also tried to even this out with the risk of having players who were very ready to share their answer, by halving points for a steal (similar to the bargaining system in I Dare You.) However, as we discuss below once again, this wasn’t enough incentive, and players simply forgot about it.

Finally, for our voting system, we thought it made sense to allow the players themselves to judge. Since our goal was to have players share with each other, we figured it would be a way to provide good feedback for the answerers, as well as a good way to show support and enthusiasm for good answers to prevent them from being too daunting. This ideology made it to the final draft: though the way we vote has changed across the drafts, along with the point values, we still think allowing players to discuss and vote provides essential interaction to each question in the game.

Testing and Iteration History

We started with an initial prototype of Dare to Share that included a complex system (rules can be found here) of action cards, stealing prompts, modifiers similar to some found in the final iteration, and bluffing. We also introduced the idea of using an online wheel spinner to select prompts, hoping it would add an element of excitement and chance.

First Playtest

Our first playtests were done with members of the class, during the first iteration of sharing prototypes. While the gameplay led to some funny moments, we found that the action cards and additional mechanics often caused confusion and slowed down the flow of the game. Players spent more time trying to understand the rules than engaging with each other’s stories. Moreover, there were simply too many mechanics – even with a full playtest, we were unable to get satisfactory amounts of information on bluffing and stealing, because players would simply forget those mechanics existed. Finally, because of the random nature of the players involved, we felt that some of the questions were simply far too awkward to give true answers to – the questions at that time were tailored far more in the direction of close friends who wouldn’t be afraid to get a little non-politically correct with each other.

Based on these observations, we decided to simplify the game mechanics for our next iteration. We made the following changes:

- We removed the action cards entirely, so the only remaining mechanics were stealing and the modifiers.

- We changed around some of the questions to be more friendly towards random groups – while our final intent was always to still include those spicier questions, we thought it would be more classroom-appropriate to temporarily remove some of them.

- We changed the point scaling – we found that when given the choice between 1, 2, and 3 points, players would almost always pick 2 because it was middle-of-the-road. We therefore expanded the range to become 1 to 5 points.

Second Playtest

We also tested the second version with classmates during class. The simplified ruleset was easier to grasp, and players jumped into sharing stories more readily, which was helped both by the improved question set and also by having players that were more willing to dive into the embarrassment entailed in the game. However, we noticed that the online wheel, while convenient for keeping the game materials compact, ended up being a bit cumbersome. It required one player to manage the technology, which took away from the social interaction; furthermore, we ran into many cases where players would get repeats of previous questions, especially later into the game where most prompts had been used. In addition, several players noted that there were difficulties with voting – in this version, we had the moderators keep track of an anonymous, heads-down voting system, which slowed the game down a lot. In addition, that required a moderator (us), who wouldn’t be present in a real playthrough of the game. We did, however, find that our issue with players all picking the median point value was somewhat mitigated by the expanded range. Finally, players determined that the modifier system didn’t feel motivated enough – the point bonus wasn’t enough to convince players to do things that could complicate their answers a lot more, and the modifiers were presented too scarily to be an option. Similarly, they almost never were incentivized to steal questions – they’d only receive half the points for stealing, which wasn’t worth it enough to brave the spotlight.

Taking all this into account, we made some significant changes for our final version (rules here):

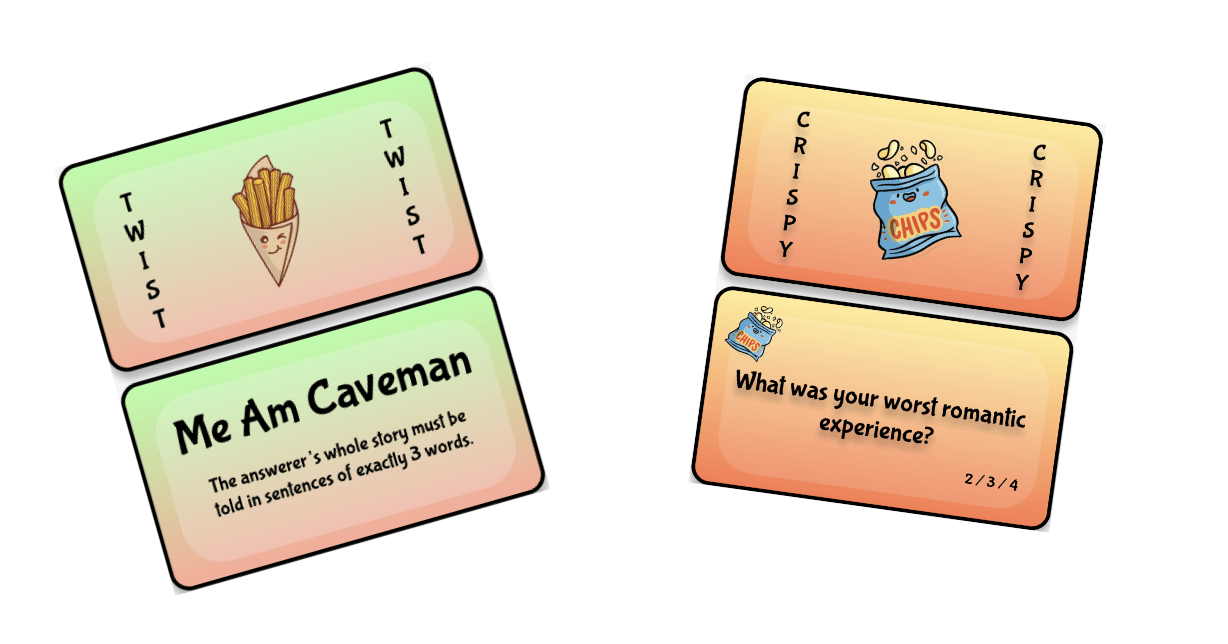

- We transitioned away from the online wheel and created physical card decks for the prompts and modifiers (now called “twists”). This made the game more tactile and engaging, and solved the issues with having to use the spinner and potentially getting the same question.

- We reworked the voting system: instead of voting after every turn, which interrupted the flow, we now have the group confer and award points based on the spiciness and quality of the story. This keeps things moving and puts the focus on the stories themselves by prompting answerers to defend their answer, and even provide more context if necessary to get points. In addition, this system no longer requires a moderator.

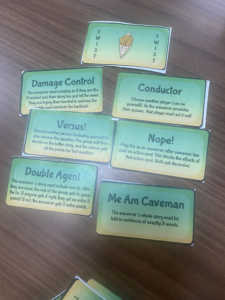

- We reimagined the modifiers as “twist” cards. Instead of just making the prompts harder, they now add fun, silly challenges to how the stories are told. Many of the modifiers no longer make the answers themselves more embarrassing; instead, they twist how the answers are delivered, so that the fun and enjoyment is split more evenly between the story and the storytelling.

- We turned the twist cards from optional bonuses to an answer, into cards that players could play on each other. This made them more common, since they felt less like self-inflicted punishments and more of ways to force other players to do something funny. The modifiers no longer held extra points, since we didn’t want to discourage players from playing them out of reluctance to give their opponents the chance to get ahead.

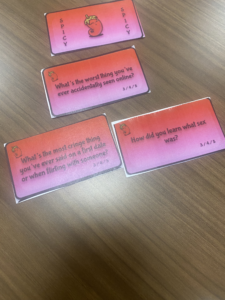

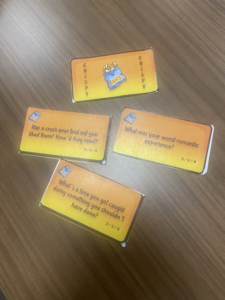

- We adjusted the prompt content, focusing on questions that would elicit entertaining stories while still allowing players to decide how personal they wanted to get. We also split them into three categories (chill / crispy / spicy), which allowed players to determine which questions they felt comfortable answering, and expanded the set of questions so that we didn’t run out of cards.

- We changed the steal mechanic to a versus mechanic that was simply one of the twist cards. This gave players the opportunity to put themselves, or another target player, in the spotlight in addition to the actual answerer. Then, the rest of the group would vote to award all points to the better answerer. This solved two problems: it made it more likely that people would use the mechanic (they are not the only person answering, and also, the point incentive is better); and it made the trigger condition more strategic, so that overly brave players couldn’t just blindly steal every question and monopolize the points.

Final Playtest

The final playtest went pretty well! Overall, players were much more receptive to the set of questions that we provided, and we noted that different players chose from different difficulties of cards, as according to how willing they were to share. The fact that players would often stick to the same difficulty of card, while it could be argued suggests that players didn’t open up enough, also suggests that the different difficulties provided safety for players who simply just didn’t feel comfortable enough to tell the worst of their stories, thereby reaching an audience of not just the most daring players. At the same time, we saw a pretty good balance of difficulties.

An interesting initial dynamic amongst the players was that most, but not all, of the players were already good friends. However, there were several outsiders. Interestingly enough, the players generally didn’t take too harshly to that, and it seemed like as the game continued, players warmed up to each other and to telling more detailed stories in a more exciting and sensational fashion – exactly the type of delivery we’d hoped to hear.

Modifiers were also used a lot more often. Players would look at their available modifier cards pretty constantly, and would consider when was a good question to utilize the modifier on (there are several instances, in the video, where we see players holding onto their modifier card until they find a question which they think it would be funny to match the modifier with; see 36:00 for an example.) It seems that players generally enjoyed using the modifiers, and they tended to add a lot to the question (one particularly good example in the playtest involved a charades-based modifier, where the entire group was engaged trying to guess what the answerer’s story was about based only on their actions; see 30:09 in the playtest video.)

The point system was also fair. One worry we had going into the final playtest was that players would be too focused on their points, and as a result might not judge other players’ answers very well. However, the 20-sided die were unobtrusive enough that while players could check each other’s scores, they weren’t a constant reminder of who was ahead. Moreover, it seemed like players judged each other’s answers based on a good blend of the storytelling and the story itself, which is exactly the reaction we were going for (see 12:50 in the playtest video for a pretty good example of how judging went.)

One thing that we could work on is figuring out how to have a more controlled environment. Though this didn’t happen in the playtest, players afterwards said that some of the questions could be answered in a way that could potentially make other players uncomfortable with the information shared. While it’s difficult to strike a balance between still having spicy, semi-universal cards and being safe, we implicitly assumed understanding of the group would satisfy that; however, this doesn’t always work if not everyone playing knows each other. Including a “trigger” discussion beforehand might be a good idea, in future.

Another point of improvement was figuring out how to “pass” questions. In game, we simply decided that players could redraw cards if they really did not want to answer, or if the question simply did not apply to them (for instance, “What was your first kiss?” might not apply to everyone.) While this seemed to work out well, players in feedback suggested that it might be better to pick more universal questions in the future to avoid this situation.

Final Prototype

Rules Doc – here

Figma Design Doc – here

Questions List (same as featured in Figma) – here

Documentation

Final playtest – here

Front cover (art was DALL-E generated):

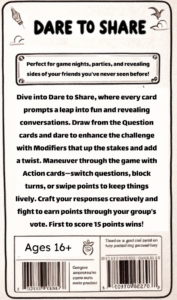

Back cover (art was DALL-E generated):

Some pictures of the game: