For this week’s critical play, I played Dear Esther, a walking sim released and published by The Chinese Room. I specifically played Dear Esther: Landmark Edition which was published on Steam in 2017 by Secret Mode and developed by The Chinese Room and Robert Briscoe. In Dear Esther, the player controls the narrator in first person and walks around the island. As the player walks, narration occurs which gives bits of information about a tragic story of grief and melancholy. Along with mouse movements to control the narrator’s viewpoint, walking is the core mechanic which slowly reveals the story of Dear Esther.

Walking tells the story of Dear Esther by slowing the play experience and allowing the player to get fully immersed in the environments and voiced dialogues of the narrator.

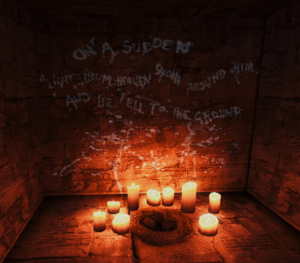

The core, and only, mechanic of Dear Esther is walking. As the player moves through the environment, they can control the mouse to look at the surrounding environment. As you walk, you find a variety of strange artifacts. There are candles scattered all around the map and strange writing (both chemical molecules and text) on the walls as you walk towards the beacon tower. Each of these strange items adds to the mystery and encourages you to keep walking forward. There’s more to learn, you just have to keep walking. Walking also slows down the pace of the game. As I was walking, I found myself constantly looking all around in my environment. I would find a path leading off the main one and would stumble across more candles or a whole underwater section in the caves area.

Candles and Writing on the walls serve as important details in the environment of Dear Esther

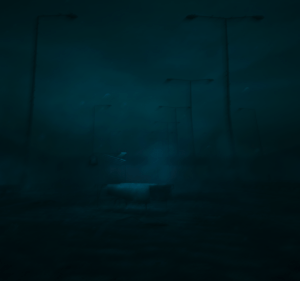

The environment seems to serve as a metaphor for the narrator’s condition. The most obvious part of the game where this happens is when you fall into a hole with water, but you end up staring at a hospital bed which has been submerged in water. After walking forward, you return back to the cave as if nothing strange ever happened. It’s experiences like this that really pull the player into the narrative and mystery of Dear Esther.

A medical bed submerged underwater

At certain parts of the environment, the narrator’s voice will start to talk to you. The narrator reads from letters, presumably written for a character named Esther (assumed to be the narrator’s deceased wife or otherwise important person to his life). As the player explores different environments such as small houses made of wood and stone to large caves filled with water, the narrator provides dialogue that hints at the death of Esther, the involvement of Paul (who may or may not have been drunk), and ends with hints of the narrator going to heaven (presumably to meet with Esther and Paul). Since each dialogue only hints at the greater story of Dear Esther, each dialogue pieces only enriches the narrative and mystery surrounding Dear Esther.

The narrator will talk to you as you walk across the island

The more you learn about what happened between the narrator, Esther, and Paul, the more you want to move forward. Walking is that method of walking forward. Dear Esther thrives with fun through narrative and discovery. At the beginning of the game you know nothing about the island and the circumstances which lead the narrator to the island. By the end of the game, you’re still unsure of the whole story, but you know that you found clues in both the voice dialogues, the environment, and that final cutscene. Walking lets you experience everything in the first person just as if you were there yourself.

Dear Esther is a different type of game than what I am used to playing. By allowing players to walk forwards without any obstacles, Dear Esther promotes exploration and invokes fun by presenting pieces of a story that the player must combine together.