Skribbl.io is an online multiplayer drawing game by ticedev for players ages 12 and up. The game’s mechanics and systems are simple enough for a younger child to grasp. Still, the lack of moderation and the more mature vocabulary with words like “Pistol” in the drawing pool suggest the game is at least for teenagers and above.

Interestingly, Skribbl.io introduces judgment through a system that operates independently from the game’s scoring mechanic. While players can like or dislike a drawing and comment about the quality of the work in the live text thread, the opinions of other players on the quality

of the drawing do not affect how well a player performs point-wise. A player can thus be judged harshly by others without their actual in-game performance remaining relatively unharmed. However, players’ ability to judge the work of others still plays an important role in maintaining the ecosystem of a Skribbl.io group. While a player is not tangibly rewarded or punished by the judgment of other players, the game encourages group discussion and socialization through its voting mechanic to establish, preserve, and enforce group norms.

The Like Mechanic

Players can leave a Like or Dislike on the current drawer’s work as someone presents their drawing to the assembled artists. This opinion is immediately made public to other players through an icon that appears by the judger’s handle and a brightly colored message in the chat. This mechanic facilitates interactions between players, allowing others to respond to the vote through a vote of their own or their text. Thus, the game has created an effective critique system where one person communicates their thoughts and encourages others to do the same, cementing the room’s group norms.

In my Skribbl.io room of random online players, the Like mechanic was used much more frequently than the Dislike mechanic, mainly to signal to the artist that the drawing they had created was easy to guess due to its quality. This mechanic does not reward players beyond fulfilling the psychogenic need for achievement by having them earn approval and praise from other players through chat messages and green Thumbs-up logos. As a result, two separate game objectives result in a feeling of achievement: earning points to win and earning approval through other players’ judgment.

With every round that passes, more Likes are awarded, with a bulk of them concentrated around a few drawings each round. Over time, players communicate with others about the drawing they find most representative of a “good game” of Skribbl.io, typically a high-fidelity drawing that allows most players to guess correctly without breaking the game’s rules. The hunt for this approval thus encourages artists, myself included, to match the implicit group norms established by the public judgment of other players, establishing fellowship as a player’s primary source of fun while fulfilling the psychogenic need for achievement through approval. Skibbli.io has encouraged real-time feedback to every player about how well they perform in their role without connecting it to their point system, allowing for honest judgment without incentivizing players to alter their judgment to improve their score artificially.

However, because Likes do not generate points, players are not strongly encouraged beyond social approval to produce good artwork that adheres to the rules and group norms. Players should be rewarded with points for making work that makes other players happy and contributes positively to the game. Skribbl.io could improve this by taking the approach of games like Apples to Apples, where approval awards points, but instead of awarding approval every turn, awarding a bonus to the player at the end with the most Likes. This would encourage users to pursue social acceptance more, improving group norms, but potentially at the cost of reducing the amount of feedback, given that players are unlikely to award likes that may give an opponent an edge.

The Dislike Mechanic

The Dislike mechanic works alongside the Like, allowing users to publicly announce to other players that they do not like the artist’s drawing. However, this mechanic is less effective at encouraging artists to engage in positive fellowship. This judgment enforces the Skribbl.io group norm of creating drawings that depict a specific word accurately without writing or giving the players the answer. The social stigma of receiving mass dislikes is expected to activate the psychological instinct to avoid loss, thus steering players that err back to the game’s rules. However, because Dislikes do not affect the points received by players who guess correctly or the artist, there is no real consequence for players who cheat beyond nontangible disapproval.

Here, there is a conflict between fulfilling the psychogenic need of achievement by scoring the most amount of points (by writing out the word) and the need to avoid shame. Because shame is not reflected in the point values that determine the winner, the need for points ultimately trumps enforcing group norms through dislikes. Players could decide to kick a player like the one to the left, who would write out the word every time, but because guessing correctly awards points, it becomes strategic to take advantage of players who simply give out the answer, even when it goes against the rules.

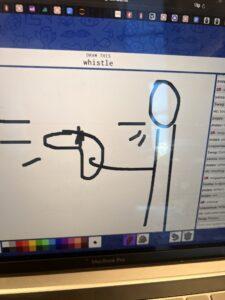

Many players in my games felt that the Dislike was not enough to communicate disapproval given its lack of consequences, so they resorted to verbal commentary bordering on abuse at many points. With poor drawings, like my whistle that accidentally became a pistol because of my lack of artistic direction, new players are driven out by Dislikes and verbal abuse. While the chat feature improves fellowship amongst players who agree by allowing communication beyond votes, this mechanic can be abused to harm unskilled artists.

To remedy this, Skribbl.io could limit the number of Dislikes one player can give out to prevent spam and increase the impact of a dislike vote. Alternatively, eliminating Dislikes altogether and focusing on encouraging positive feedback while awarding players for receiving Likes could steer group norms in the right direction without making room for negativity. Players could still keep the option to report or kick a player by popular vote if they do not adhere to game rules. Still, the average level of negativity would be decreased in favor of strictly positive feedback.