Scribble.io is an online, multiplayer Pictionary-like game designed by ticedev. Allowing for private and public rooms, this game seems to be designed for strangers and friends alike. Anyone familiar with the vast majority of words in the game (I’m guessing eight to ten years old) could enjoy Scribbl.io, although the public lobbies should probably have a higher minimum age requirement (perhaps 16) due to the lack of moderation on the site. For this critical play, I played in public lobbies. In this game, “judging” isn’t a mechanic itself. The central mechanic is guessing the word that’s being drawn. However, the way in which points are awarded lead to judgment of the drawings as an emergent dynamic. A different mechanic–the ability to votekick a player–leads to a different level of judgement. This meta-level is about judging the player rather than the drawing. Taken together, if there is a critical mass of well-meaning players, these two levels of judgement can facilitate fellowship and challenge. Without this critical mass, however, the game loses its challenge, becoming mean-spirited and dull.

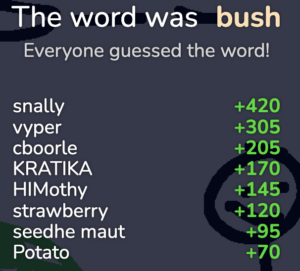

When a player draws, they get points based on how many and how fast people guess their word. This incentives the drawer to get as many people to guess their word as quickly as possible. Guessers receive points based on how quickly they guess the word. Guessers are motivated to get the word right because they earn more points than they end up giving to the drawer.

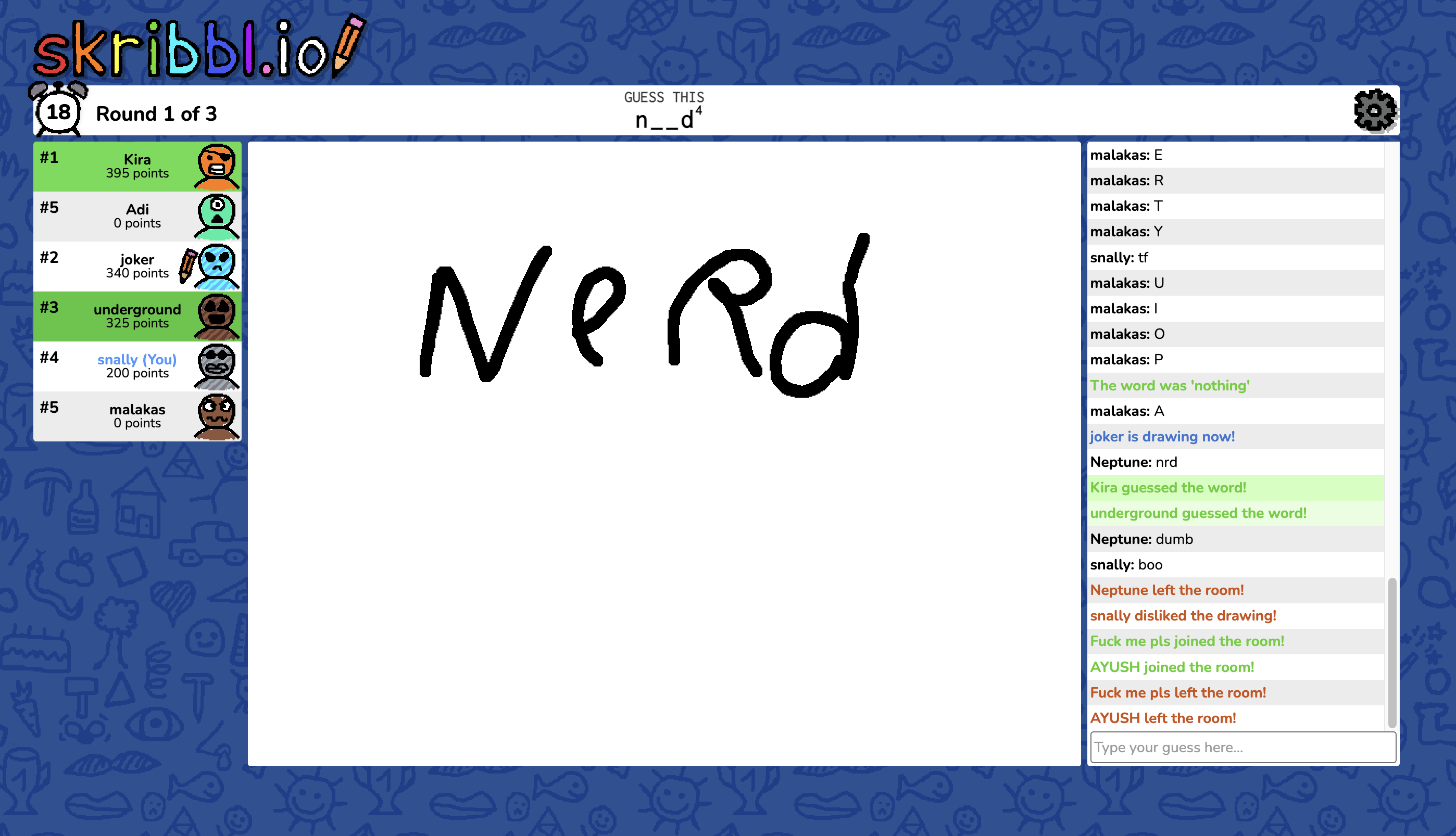

The challenge of this game lies in trying to figure out the words being drawn as fast as possible and in trying to draw the words as clearly and as fast as possible. This challenge rests on the rule that no writing is allowed. Despite this rule, people do it all. the. time.

Any round where the drawer uses this “strategy” loses its challenge and therefore its fun. Ideally, people wouldn’t guess the word so they wouldn’t reward the “drawer” for their game-ruining behavior, as shown above. Unfortunately, this was the only time everyone held strong and refused to give the drawer what they wanted. Every other time, people knew that if they were the first to guess, they would get more points and, since they thought it likely that others would guess, they didn’t hesitate to do so. I found myself falling into this trap many times, wrongly rewarding breaking the rules.

This is where the other type of “judgment” comes into play. At any time, a player can “votekick” a different player. If more than half of the group votekicks any one player, that player is booted from the lobby. In one of the lobbies where I played, people were readily willing to kick out these annoying cheaters. Protecting the integrity of the game brought the players together. These rounds involved more compliments on people’s (actual) drawings and less blaming of the artists when people couldn’t get the word. The meta-game, where you have to fight to actually play the game itself, had ramifications within the actual game.

But they weren’t always positive. In one lobby, I was the only one to votekick these cheating players. Instead of helping me get rid of these fools, other players adopted the same “strategy” and the lobby was just people writing the full word or blatant written clues (“I fly planes” for pilot). In the chat (which doubles as the space where people guess the words) people were much more mean spirited than in the other lobbies, insulting the drawings of the people who were trying to play the game.

Scribble.io, when stripped of its intended mechanics by rule-breaking, becomes a much less engaging experience. Naturally, the fun of the game relies on everyone playing by the rules; without that, it loses its essence. I wonder if reshaping how the points are given out can reduce the allure of the game-breaking strategy. Perhaps guessers can decide how many points they think the drawer deserves. Perhaps they’re only given this option if some machine-learning algorithm detects letters in the drawing. Until that feature, or something similar, is implemented, Scribbl.io is best played with people you know.