Skribbl.io is a game created in 2017 by developer ticedev. It’s a drawing competition game for 2-12 players and takes about 10 minutes to play, although this depends on custom settings like the number of rounds played and time per round. There’s no explicit age range, but based on my observation, people above 10 can play and succeed. As far as I know, the game only exists in an online version, but I can imagine it could be easily created in real-life.

The mechanics are fairly simple. Each round, one player is selected as the “drawer,” and they choose one out of three words to draw on a digital whiteboard. The rest of the players have a chat box where they can type as many words as possible until they correctly guess what the word is. As a guesser, you win more points by guessing quickly, and as the drawer, you win more points by getting your drawing guessed correctly as fast as possible.

Argument: In skribbl.io, judging is used for players to compete and win the highest amount of points, creating a point progression system and dynamics of competition, cooperation, and social fun. At a lower level, there’s also aspects of “unofficial” judging that creates aspects of collaboration and rivalries.

Skribbl.io is a judging game at its core because you’re trying to guess what one person is “scribbling” to earn points. Judging means “to form an opinion or conclusion about something,” and in skribbl.io, you’re essentially concluding what the drawer’s prompt is based on how clearly they draw a picture of it. As a drawer, you’re attempting to draw the most clear picture so that people guessing or “judging” will do it as fast as possible, netting both you and the player points. The word prompt you have to draw can either be random or picked from a custom pool you create. This judging aspect encourages direct competition between the non-drawer players, since they’re racing against each other to guess the fastest. It focuses heavily on challenge and fellowship.

In another sense, the judging aspect fosters collaboration between the drawer and each individual player, as the former needs to work with the player for them to both win points on that round. The judge can read the chat box, and based on how closely the players are guessing, he can adjust his or her drawing to correct any erroneous lines of thinking from the players and get them closer to the answer.

There’s also a few less formal aspects of judging in the game. Because the chat box option doesn’t have any restrictions (except for obvious profanity words), players have the freedom to talk amongst themselves. I noticed that when I played with close friends, there was a lot of trash talking, allowing players to judge each others’ responses, which created light-hearted rivalries and grudges. For example, if one player guessed obviously incorrect words, the other players would laugh at him or her in the chat. They would also laugh at the drawer if his or her creation was terribly drawn. This strengthened the social dynamic of the game because it encouraged players to talk and engage in banter. There were hints of the proximity law of friendship building, since players all shared the same goal, and players could see how similarly or not they guessed. Although this was fun, I can imagine how it would ruin the experience for some players, taking them out of the game’s “magic circle.” To solve this problem, there should be an option to limit chat box entries to single words (or however long the prompt is). I tried playing with random people, and I noticed the anonymity encouraged us to be more civil.

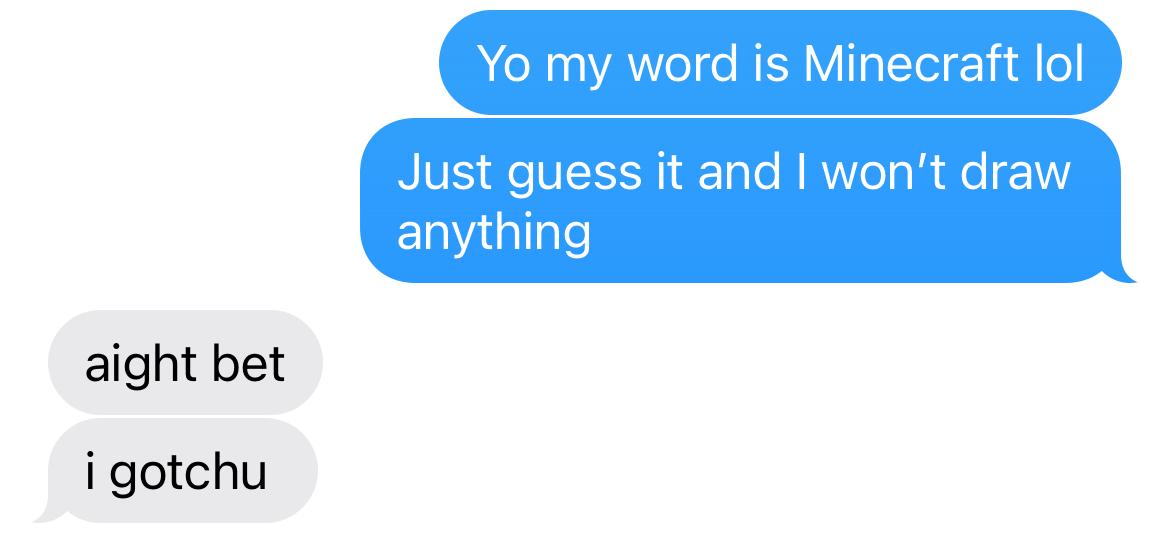

Upon debriefing with the other players, I learned that some of them had also broken the “magic circle” and colluded amongst themselves. For example, two players cheated by telling each other the word over iMessages. There was no rule explicitly banning this, so they assumed it was okay, and this created a new collaborative dynamic for unofficial teams to judge together. To solve this problem, we could create new rules, or we could play this game in-person and lock the players’ screens so they can’t collude.

As a game designer, there were a few lessons I learned from skribbl.io. First, I realized that to create social dynamics in a game, you don’t have to do much. If you let the players interact freely with something as simple as a chat box, you allow them to create their own social dynamics—whether it’s banter, competitive rivalries, or collaboration. The mechanics of the game, which required constant typing, definitely contributed to this.

In conclusion, skribbl.io offers a fascinating yet simple way for judging-based gameplay. It fosters the social dynamics of collaboration and competition, giving power to the player to decide how they want to play. The aspects of guessing, chatting, and a point progression system shaped a fun, complex social experience.