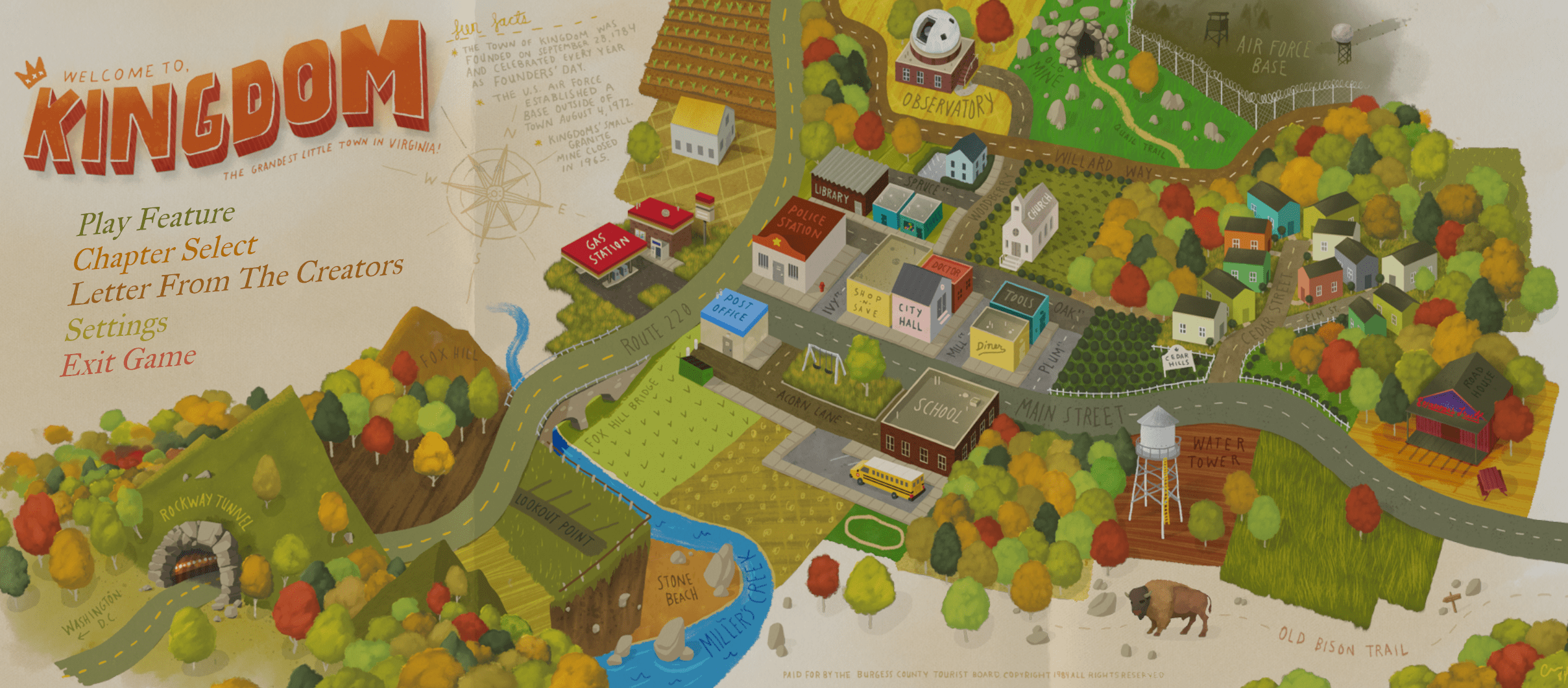

Virginia is a single-player game and experience developed by the game studio Variable State that encompasses mystery, walking, and narrative storytelling. Although it is available on various platforms like Xbox and Playstation, I bought and played through the roughly 2-hour game on Steam for a reasonable $10. Although it is a short game, it is PACKED with narrative, with dense information between every cut. This game is for those who crave mystery (calling all narratologists!) and enjoy putting pieces together to uncover larger secrets.

Figure 1: A screenshot of the opening scene, where you walk down a hallway to get on stage with the FBI executive

I’d argue that this game focuses on achieving a certain narrative rather than introducing fun through specific dynamics. Instead of being mechanically different from other games, Virginia plays as a walking simulator with a unique storyline. To achieve this, Virginia works around the concept of limitations to amplify its narrative and mysterious undertone. Whereas a typical story typically has dialogue, transitions, and written-out revelations, Virginia has none of these. Instead, the player relies on cues like facial expressions, lighting, sound, and even the speed at which different people perform actions to understand what the game is trying to portray. In terms of the mechanics themselves, all the player can do is walk around the rooms they are placed in and, with the click of a single button, interact with various objects and the environment in different ways. In this critical play, I will comment on three things that Virginia employs to create a compelling narrative game: (a) how the game creates an overall narrative through embedded micronarratives, (b) how the conscious decisions that were made by the developer to “cut corners” yet amplify this narrative, and (c) highlight symbolism that is used to shift the player’s thoughts and emotions throughout the game.

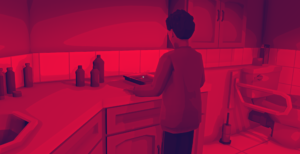

Figure 2: Ominous mood lighting that foreshadows that something major is about to happen; I talk about this more in the last section

How is narrative woven into the gameplay?

One of the key points of a mystery game is the ability to convey information in a way that is either interpretable in many forms or is initially meaningless to the player until they discover more. In Virginia, the player often does not know what is happening or what their actions may do. The game starts in a bathroom without explanation; when they leave, they suddenly find themselves in a crowd with hundreds of FBI agents applauding them. The game utilizes heavy cuts to remove redundant information yet still includes an abundance of micronarratives. For example, in one scene, the player wakes up to an alarm clock and, unable to turn it off, has to act to hit the clock forcefully to stop it. In another scene, the player might walk through a series of hallways (with cuts in between) just to arrive at Maria Halperin’s office. These scenes, although they seem insignificant on their own, actually contribute to a larger story: the clock portrays the protagonist’s annoyance by replicating a familiar alarm clock experience, and the long hallways describe how the journey to Halperin’s office is not insignificant—the protagonist, any time they go to Halperin’s office, is making a conscious effort to walk all of the way there (this could have also been one cut directly to her office). Combined with parts of extremely meaningful information, the game feeds information to a player in small increments that precede major breakthroughs. It distributes these revelations to prevent the player from getting into a routine; one moment, I’m eating breakfast with Halperin, and in another, I’m in the records room, uncovering her history with the FBI.

Figure 3: An image of the silenced alarm clock after the protagonist gets out of bed

Figure 4: An image of a screen that the protagonist finds while looking up Halperin on the records list

In this section, I also want to answer the question: Why not just tell this story in a book? I argue that having this narrative in a game adds a layer of immersion that would not be possible with walls of text. I was pleasantly surprised about the number of flashbacks that I could physically live through (such as flashing back to when Halperin was a friend after she discovered that we were tasked with investigating her), the could-be moments that never really happened (such as climbing the ranks to become the new FBI assistant director), and the seemingly magical moments that the protagonist experienced despite being completely fictional (such as having an elevator burst through the wall). It made the experience shorter than reading literature yet more engaging.

Figure 5: One of the aforementioned “magical moments”, where the player is hallucinating something happening to portray a deeper conflict

What are some conscious decisions of the developer that amplified the game’s narrative?

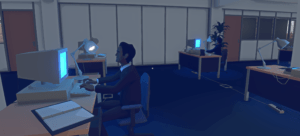

Another thing I appreciate about this game is its ability to cut corners while maintaining clarity. One of the first things I noticed was the lower-poly assets and the lack of detail towards redundant information (for example, the computer screens in the FBI office being completely blue). Some other deliberate choices included isolating dialogue from the player, utilizing lighting to set the mood (a very popular one in this story was red representing something hidden), switching the character the player controls (most commonly used towards the end after the protagonist takes the LSD tablet), and, as previously mentioned, the frequent cuts between scenes. This ability to cut corners makes me think about how my team will approach P2; removing effort while making the game seem pristine seems like a skill that we’ll have to practice as the deadline gets closer and closer. Although I was conscious about these decisions as I played through the game, at no point did I ever think that it negatively impacted my player experience. (At some points, it created a bit of confusion, but just enough to keep me curious about what was going to happen next.)

Figure 6: A moment I noticed that helped the developers “cut corners”; filling the computer screens with bright blue

How did the developer use narrative techniques like symbolism (loops/arcs) to convey mystery?

The symbolism in Virginia takes place both in physical objects that the player interacts with and the scenes that are commonly repeated (the loops and arcs). Some symbols that are repeated throughout the story are the color red, the broken key, and the dead cardinal. Each of these, when placed throughout the story, give the narrative some cohesion that brings the player back to a certain idea (for example, the color red typically symbolizing a major plot point, such as being initiated into the FBI or revealing the photographic evidence). Although there are several symbols, the number of repeat locations is even greater: the drive with Agent Halperin, the outside of the observatory, the diner that the protagonist and Halperin frequent, the director’s offset, Halperin’s office, etc. This also serves to my second point with the “cutting corners”, as the developer can re-situate the player in a scene that was already modeled; however, it also grounds the game into a set of different scenes that the player can be familiar with. The final time I went back through the series of hallways to Halperin’s room, I already could feel a sense of dread when I knew that Halperin had discovered my plans to scout her out.

Figure 7: Symbolic mood lighting; the game makes the player associate “red” with a secret or major plot development

I would summarize Virginia as a complex story packaged into simple mechanics. After the game ended, I was surprised to see I had experienced so much in under two hours. If you’re a person who wants to be brought through a rollercoaster of various scenes and emotions in such record time, Virginia is the game for you. 🙂