Sushi Go is a social deck-building game that attempts to facilitate fellowship between players by having them collect cards from multiple hands of cards with a few cards that do not give points but give the player special abilities or bonuses. Similarly, Pizza Pizzazz encourages player interaction through a card economy mechanic, where cards are removed from play and into a player’s hand, and through special effects, where different cards vary in how they are applied, giving players more opportunities to interact. However, Pizza Pizzazz aims to amplify the social dynamics produced by these mechanics by amalgamating the accessible pool of cards to pull from into a single set and having card effects directly impact other players and their collections rather than simply their own. I will use the following two sections to compare and contrast Sushi Go and Pizza Pizzazz through the lens of these mechanics and their effects on creating fellowship.

Mechanic 1: A Set of Cards to Pull From

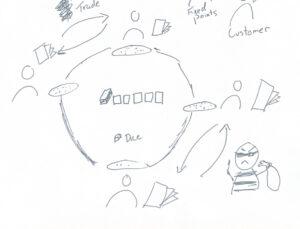

By leveraging the mechanic of collective access to cards from Sushi Go, Pizza Pizzazz similarly fosters fellowship by giving players access to a pool of visible cards that every player can pull from on their turn. However, because the pool of collective cards is singular instead of spread across multiple hands, players are reminded and encouraged to take essential cards from the center as soon as possible, giving players more agency over the cards they can select. Pizza Pizzazz thus creates social dynamics where players audibly strategize to take the best cards for themselves or take valuable cards away from players who need them. This, in turn, creates opportunities for alliances, banter, and deals as players try to keep the cards, which may help or hinder them, in the center and out of the hands of other players.

This differs from Sushi Go, where players can only see the cards in their hand and can only take from their own cards on their turn. In my playthrough of Sushi Go, our approach was to “take the highest-value card” from the hand available to us. Strategizing more than two hands in the future was rare for us first-timers, given that the fast pace of the game and the sheer number of cards do not allow for memorizing every hand that passes by. This hindered the social capabilities of the game as every player was much more concerned with the deck they were building, with little reason to track the cards other players were collecting. Players rarely made the connection between the cards others took from their hands and how this impacted their own collection strategy. So, there were fewer incentives to sabotage other players or take cards that may not be worth as much to you but are to others. The Pudding cards are a prime example since players must simply collect enough to not be last at the end of the game. This limited social engagement led to players collecting just enough Pudding to stay away from last place. Still, it did not encourage any social dynamic beyond glancing at how many Pudding cards the other players had – no one was fighting over collecting the dessert; they were simply collecting enough to buff their point count at the end.

This differs from Sushi Go, where players can only see the cards in their hand and can only take from their own cards on their turn. In my playthrough of Sushi Go, our approach was to “take the highest-value card” from the hand available to us. Strategizing more than two hands in the future was rare for us first-timers, given that the fast pace of the game and the sheer number of cards do not allow for memorizing every hand that passes by. This hindered the social capabilities of the game as every player was much more concerned with the deck they were building, with little reason to track the cards other players were collecting. Players rarely made the connection between the cards others took from their hands and how this impacted their own collection strategy. So, there were fewer incentives to sabotage other players or take cards that may not be worth as much to you but are to others. The Pudding cards are a prime example since players must simply collect enough to not be last at the end of the game. This limited social engagement led to players collecting just enough Pudding to stay away from last place. Still, it did not encourage any social dynamic beyond glancing at how many Pudding cards the other players had – no one was fighting over collecting the dessert; they were simply collecting enough to buff their point count at the end.

To avoid this, Pizza Pizzazz makes all players take from a smaller, visible pool of cards. The mechanic that allows players to take from the center constantly reminds them of the available cards that may aid their pizza-building endeavors. Because the pool of possible cards is limited to a single group, the action of one player directly impacts the rest, and their constant visibility allows for immediate fellowship through emotional reactions, celebration, and indirect sabotage when one chooses a card. When a card is taken, particularly a high-value one, players around the table experience the immediate consequences of a card pulled out of play. This is a departure from Sushi Go’s formula, where every player is unlikely to notice which handful of cards have been “stolen” from them once their original hand makes it around the table. The reduced amount of collectively accessible cards also increases the scarcity of high-value cards, increasing the investment players have in access to the cards in the small center pool, manifesting in new social dynamics, such as players bargaining or manipulating to keep cards they need in the center until they can grab them for themselves. This is in stark contrast to Sushi Go, where one is highly likely to find a replacement card in one of the 32 cards being passed around the table, making other players’ collection choices less impactful to the rest of the players.

Mechanic 2: Special Effects

Pizza Pizzazz uses special effect cards to introduce some variability to the game beyond ingredient collection, similar to the Chopsticks and Wasabi in Sushi Go, which allow players to take another card or increase their score, respectively. These abilities spice up the deck-building aspect of the game, but unlike Sushi Go, the special effects in our game go beyond boosts to one’s own points or abilities, which only affect the player who activates the card. To encourage more fellowship (or anti-fellowship), Pizza Pizzazz instead uses special effects like stealing, trading, or sabotage, which require interaction between two or more players.

A notable moment from my Sushi Go game was the sudden player realization that some hands had one less card than others. After some confused looks and worries about making a counting error, one of the players spoke up to tell us they had used the Chopsticks to take an extra card earlier. “Oh, alright,” we answered, but because the use of the most powerful card in the base game was an effect that could be applied quietly to one player during a round, it had gone largely unnoticed. To avoid this, Pizza Pizzazz’s special card effects affect multiple players on the board, giving social leverage to whoever possesses the stronger cards. Players can bargain to be exempt from ingredient theft or form alliances to target players in the lead. This way, the exciting dynamics of special effect cards still exist to give players an edge, but social interaction becomes a preemptive strategy or a direct consequence for the players, depending on who uses the card.

Sushi Go’s approach to boosts works because they are rare and limited in scope, like the Wasabi only being able to pair up with specific Nigiri cards. These simple effects are seasoning to the game’s base mechanic, collecting ingredients without overpowering it. Sushi Go’s simplicity warns us about over-complicating Pizza Pizzazz or distracting from its core pie-building by introducing too many power-ups that affect multiple players. Still, through playtesting, we hope to introduce enough socially interactive special effects that create healthy chaos and get players talking while preparing their pizzas.

— Francis