Game: Spyfall

Creator: Alexandr Ushan

Platform: Web App

Target audience: Broad audience of teens, adults, and possibly some children. Group of 4+

Spyfall seems precision-designed to solve many of the most common problems social deduction games face, and it does so without forgetting the core of what makes the genre so much fun—the social deduction (and its counterpart social deception) itself. The remainder of this critical play will be structured around each of these four problems and how Spyfall solves them.

#1 — The Information Void

At the start of many social deduction games, players have very little information. In the game of Mafia we played in class, my group wound up choosing who to execute based on the theory that a mafia member was more likely to eliminate one of their friends than someone random. Even in more complex entries in the genre, such as Secret Hitler, players gain information largely based on who passes what policies, which is both slow and unreliable.

Spyfall flips this on its head. Here, the majority all start knowing something the spy doesn’t: a location they are all at, such as a bank or a submarine. It then uses this in its core mechanic: players take turns asking questions of each other about the location to deduce who knows what the location is, and by extension, who is the spy.

This process gives players information right out of the gate, before any decisions about who to accuse or who to make chancellor have to be made. In doing so, players are immediately thrust into the good bit—tension and deduction.

#2 — The Attention Problem

In many social deduction games, the center of attention isn’t a good place to be, regardless of your role. This creates a dynamic in which players try to participate as little as possible to avoid divulging information.

Spyfall fixes this in the same way as the information void—players are constantly asking each other questions, and you have to answer the question. After you answer a question, you get to ask one to someone else—but it can’t be the person who just asked you, ensuring the spotlight gets spread around.

In my group, this mechanism produced a dynamic where players were expressive and communicative—rather than performing an unreadable poker face, they performed being in the in-group, exchanging glances after each strange answer.

#3 — No Way Out

Playing as the traitor in a social deduction game often offers little comeback potential. Suspicion is sticky and difficult to shake. As the walls close in, the possibility of a heroic upset narrows to a sliver.

Not so here. Spyfall offers the traitor an alternate objective—guess the location. As the other players ask each other questions and give answers, trying to find the spy, they reveal information about where they are. Even as suspicion mounts and you get closer to being found out, you also get ever closer to victory.

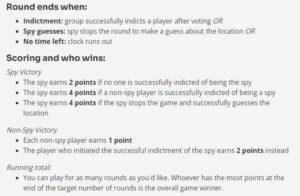

Further, spyfall changes the outcome of the game. Rather than be played over a single round, players gain points based on not just whether they won, but also how they won. As Spy, if you can get the table to falsely indict a non-spy player, you get four points (twice as many as it is possible for non-spies to get in a round). You also get four points for correctly guessing the location. As a result, rather than being incentivized to play conservatively, hanging on until the end, the spy is incentivized to try and pull off difficult and risky plays.

#4 — Each Role Gets Half the Fun

This isn’t so much a problem as a missed opportunity: social deduction is only half the fun. The other half is social deception. Just as it is fun to try and catch your friends in a lie, it is fun to, within the magic circle of the game, try and lie to them.

For many social deduction games, which kind of experience you have is dependent on which role you play. In Spyfall, all roles need to do both at once. The other players need to deceive the spy about what the location is as they try to deduce who the spy is, and the spy needs to deduce what the location is even as they deceive the other.

In one case, I asked the question “would you hear music at this event,” hoping that a ‘yes’ answer from one of my allies would point the spy towards the obvious answer (a rave), as opposed to the real location (a political protest).

By allowing players to engage with both sides of the deduction/deception coin in this way, Spyfall creates a much more layered and satisfying experience.