Through the introduction of many different roles, the option of varying scenarios, and intentional rule/phase changes, Blood on the Clocktower is a successful attempt of making a more involved and eventful version of Mafia at the cost of the original game’s simplicity. This raises the level of entry for new players but also raises the skill ceiling of the game, allowing for players to explore new interactions and situations every time they play.

Blood on the Clocktower, created by The Pandemonium Institute in Sydney, Australia, is a social deduction game designed for players above the age of 14 and best suited for large groups. My initial encounter with the game involved playing with a group of six in a physical lounge using a digital board setup. Most players were either beginners or had only played the game, at most, twice before.

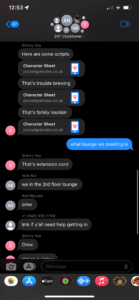

Before even starting the game, our group chat was sent multiple gameplay scripts. Each script had a completely unique premise and roles, so we settled on playing “extension cord”, the most beginner-friendly script. The general premise of Blood on the Clocktower is that the narrator was murdered on the first night and their body was displayed on the town’s clocktower. Interestingly, this change in first night procedure not only solves the issue of first night deaths but also weaves the narrator into both the story and objective of the game. This eases the burden narrators have of conjuring scenarios for why there are murderers in the town, and it also sets the premise for dead players to still be able to contribute to the conversation just as the narrator is able to speak to townsfolk. First night changes also protect the “mafia” role, as anyone is just as likely to kill the narrator. As a first-time demon, this was helpful to me.

One of the game’s hallmark features introduced on the first night was the concept of poisoning. Unless stated otherwise, poisoning does not result in elimination. Here, it warps the information poisoned players receive from the narrator when using their roles’ abilities. This twist of unreliable narrations significantly alters the game’s dynamics, introducing a layer of strategy where players must cross-reference information and cannot solely rely on the narrator’s word. The game also allows for private discussions among players during the daytime discussion phase, fostering an environment of trust and deception. In fact, I was called out for not initiating in a one-on-one discussion as it was seen as suspicious, despite my bluff role as a soldier not having information-gathering abilities.

Despite all this praise, as a beginner player, it was extremely confusing. I lost track of roles, abilities, and statuses for each player. I made the choice of the wrong bluff as choosing another bluff role would have been more advantageous for me. After the second night (where another player was killed by me), the other beginner player outed themselves as a poisoner minion as they weren’t sure whether they were allowed to lie in their role. This led to the group deducing that I was the “No Dashii” or the demon/mafia role. I believe our group would have strongly benefited from an example round or tutorial and a physical board to keep track of the known statuses of different players. Additionally, the narrator also read the rules wrong and incorrectly poisoned two other players on the first night.

Overall, Blood on the Clocktower’s relatively high barriers to entry (cost, understanding of rules, game setup) prevent it from having mass appeal similar to games like Among Us or Mafia. However, once a player steps past those barriers to entry, they will find the game to be much more enjoyable as its complexities are what makes it unique. I hope to revisit Blood on the Clocktower again to explore the other scripts, roles, and scenarios with a larger group. The limited amount of playthroughs my group had does not do the game justice for me as I can see the potential the game has.

Script Sheet: www-pocketgrimoire…