For our first critical play, I played “The Resistance: Avalon Card Game” by Indie Boards and Cards. I played the board game version, though there is also an online version you can play here. The game is suitable for 5 to 10 players of any age, though it seems to be aimed at adults.

In the game, there are two teams of players, Good and Evil. Players receive the invitation to play, when they receive their secret role card indicating themselves as Good or Evil. The game takes the invitation procedure one step further by integrating a starting process, where players reveal each other to the roles that should know each other.

Evil team members know who each other are, but Good team members don’t. That’s except for Merlin, a member of the Good team who knows who all Evil team members.

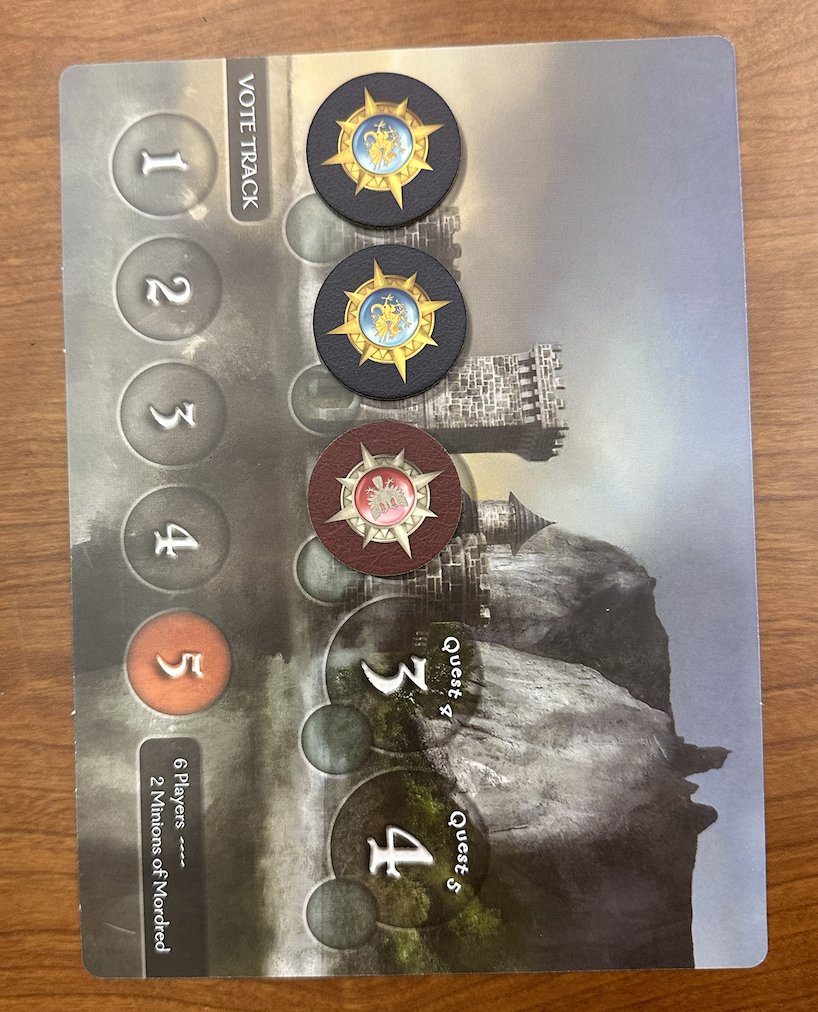

Each round, one player is given a temporary role of “leader”. This leader chooses a group of players to go on a quest, who also receive temporary “quest goer” roles. If that quest team is approved my majority vote of all players, then the players in the team will “go” on the quest. This procedure looks like each player secretly playing a card that either indicates success or failure. If there is even one failure in the set of cards played, the quest fails. If the quest team is not approved, then the next player becomes the leader and chooses another team.

The Good team’s objective is to succeed on three quests total. The Evil team’s objectives are more of a mixed bag, and they can win the game if three quests fail, five quest teams in a row are rejected, or if the Evil team is able to identify Merlin at the end of the game.

Avalon is able to emphasize social deduction by doing an exceptional job at engaging all players regardless of their original role.

The primary way in which the game does this is through it’s rotating roles of “leader” and “quest goer”. By rotating the leader role among each player, the game requires all players to take an active role by making a choice of who to assign on a quest team. This is contrasted with other games in the genre such as Mafia, where only a small subset of players with special roles can take important actions.

Additionally, because all players can be quest goers, there creates the dynamic where all players, Good and Evil, want to seem Good so that they get assigned quest goer. If a leader is Good, they will need to try to deduce which players are actually Good, and if a leader is Evil, they will have to try to sabotage the quest without seeming evil and thus ruining their chances of being assigned onto the next quest. Rather than being removed from the game, such as in similar games like Coup, players who are labeled evil can redeem themselves in the future and still affect the game when the leader role rotates to them. For example, in my game play, I was able to convince players I was Good despite being labeled as early on by choosing a quest team which succeeded when it was my turn to be leader.

Additionally, through the leader rotation mechanic which allows both Good and Evil players to be leaders, Avalon ensure that players get information the the possible objectives of each player based on who they choose for the quest. Subsequently, all players receive information about one another during the voting phase, and even more information once it is revealed whether the quest succeeded or failed. This is in contrast to “investigation” mechanic in other social deduction games, where only one player is given some information. By giving all players the same access to information, the game creates a dynamic where anyone can be a detective regardless of their actual role.

Another interesting Mechanic introduced by Avalon is the role of Merlin. In many other social deduction games, the “evil” team engages in very little actual social *deduction* because they know who all of the “evil” members are, and thus by process of elimination know who all of the “good” members are. While the “evil” team can still engage in deception, there is no point in actually keeping track of player actions and behavior because there is nothing to deduce. However, because the Evil players in Avalon also have the objective of identifying Merlin, there is a dynamic where Evil players need to continuously analyze good players throughout the game. In this way, Avalon emphasizes social deduction for it’s Evil players.