Introduction

Spyfall is a social deduction card game originally designed by Alexandr Ushan and published by Hobby World. This week, I played an online version of the game on netgames.io (created by Luke Tsekouras). Online and card versions are aimed at teens and adults (13+) and can serve as a casual party game with established or new groups.

Analysis

The objective of Spyfall is similar to many other social deduction games, such as Mafia and Among Us. The spy aims to remain undetected and identify a secret location; the rest of the players (who know the location) seek to identify the spy. Spyfall is an example of a unilateral competition, as the spy is playing against everyone else. However, playing the game can feel like a multilateral competition, since players don’t know who they can trust. Spyfall mainly promotes fellowship by learning about other players’ tells and tendencies. It also gives space for discovery, as players uncover new ways of gaining information from others. As my group played more rounds, we developed new questioning strategies that became more abstract. Instead of direct questioning, we would ask about movies involving the location or use callbacks to previous rounds.

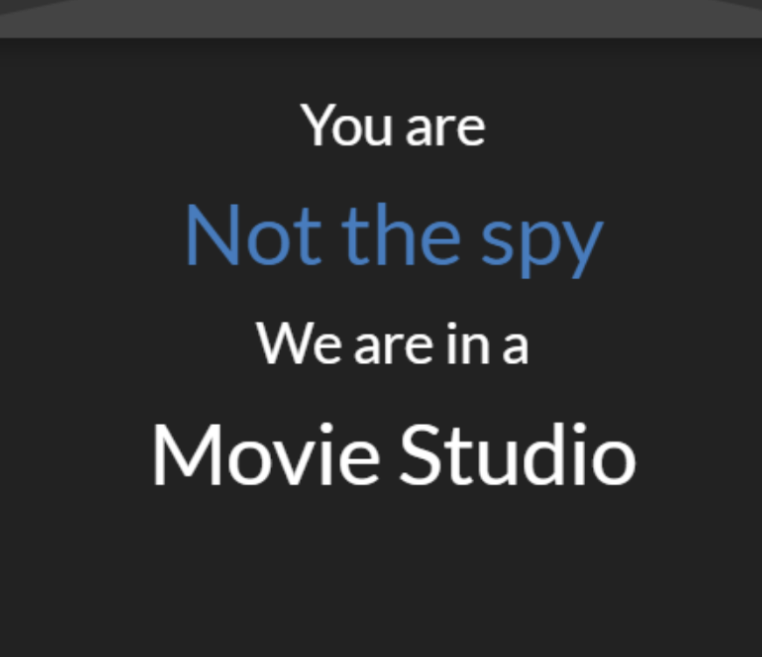

Playing the game online meant we could play remotely or in person; we chose to do the former. The boundaries depend on the methods used to host the game (any device screen or physical cards) and connect us (we used FaceTime, but Discord, Zoom, or even a physical room could work). In the online version of the game, each player is assigned a role: spy or non-spy. Non-spies will also be given the round’s location (as seen below).

The next screen contains the remaining time in the round and a list of all the possible locations. This is when the real game begins!

There are very few rules in Spyfall. Formally, the person who started the game is supposed to ask the first question, which the respondee must answer. At the end of the round, final votes need to be unanimous among the non-spies. Informally, players should maintain a social contract and not cheat by peeking at each other’s screens or cards. The outcomes of this zero-sum game depend on the player’s role. Spies can win by a) avoiding detection for the entire round (convincing players to vote for someone else) OR b) announcing they are the spy and correctly guessing the location (if they are incorrect, the non-spies win). Non-spies can also win the game by unanimously identifying the spy after the timer runs out. The online interface doesn’t describe these rules, assuming a prior familiarity with the game. The only description is shown once, in the image below.

Since we only had the information above, we were unaware of the formal rules such as the spy’s ability to guess the location, so our game experience ran longer than average and affected the ambiguity of our answers.

Unlike other social deduction games such as Among Us or Mafia, which are more rigidly structured, Spyfall’s lack of structure emphasizes social deduction by allowing players to craft a unique game experience. The primary mechanics are just the round location and timer, so the conversation itself (e.g. the types of questions asked, non-verbal communication, and pacing) is entirely up to the players. I played this game with a group of friends that I already knew, so we used callbacks and inside references to communicate information that would’ve been impossible in a different group.

Players must balance ambiguity with clarity due to the mechanic of location similarity. For instance, for the Ocean Liner location, one player asked “What type of people would you see here?”. A clever response by a non-spy was “rich people” since it answers the question accurately without giving away the location; rich people may also visit other (but not all) locations. The need to balance ambiguity and clarity meant that trust had to be built over time, as one response couldn’t be enough to guarantee a role. This dynamic influenced the flow of the game. The more trust players had in each other, the more they would target other players and not question suspicious responses from those they already trusted.

I enjoyed playing Spyfall online, though I had a few critiques. First, the online version interface was too simplistic. It would benefit from having a clearer description of the task/rules. The card version also includes images for each location, ensuring that players are on the same page. The online version only included written text, so some location names were unclear to us (such as “service station”). Additionally, the locations began to feel repetitive after a few rounds, so Spyfall may also benefit from including new categories of cards to encourage new types of questions and conversations. Finally, players might appreciate the ability to write new locations/categories tailored to the shared experiences of the group (like blank cards in Cards Against Humanity).

Conclusion

The mechanics of Spyfall are simple yet effective in promoting social deduction. The lack of rigid structure encourages users to take initiative in their game experience and develop unique techniques suited to their particular group. This skill requires players to understand each other’s thinking patterns, strengths, and weaknesses, creating a fun and engaging experience for all.