Riddleton’s Treasure: A Family Quest

Team 14 Members: Julia Chin, Cyrus Darcy, Albert Hwang, Elysia Smyers, Pannisy Zhao

About Riddleton’s Treasure

Riddleton’s Treasure is a game that calls on the nostalgia of family ties over generations, through our narrative that ties relatives over generations together in order for our protagonist, Sage, to find her family’s hidden treasure. With three female game designers on the team, we decided to make our protagonist a woman, in hopes of enforcing the notion that both men and women are capable of embarking on this adventure of puzzle-solving and treasure discovery. By placing a female character at the heart of the narrative, we seek to challenge conventional roles and empower players, irrespective of gender, to believe in their ability to overcome obstacles and achieve greatness.

In terms of gameplay, we also try to tie many different types of puzzles together in our game to leverage the discovery type of fun, in multiple different ways, from discovering how to solve our selection of puzzles to discovering new parts of the narrative as they emerge through the gameplay. We worked to make sure the narrative tied our various puzzles together so the game did not feel disjointed, and we did many iterations to make sure that we accomplished this goal, while ensuring our other core values shined through.

Ultimately, Riddleton’s Treasure is a celebration of the human spirit, reminding us that true treasures lie not only in material wealth but also in the experiences and relationships we forge along the way. This game serves as a catalyst for fostering connections, whether through cooperative gameplay or competitive strategies. It invites players to engage in meaningful interactions, fostering a sense of community and shared adventure.

We hope that these values of family ties, discovery, feminist representation, and challenging gameplay shine like a seastar when you play Riddleton’s Treasure!

Link to final playtest video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cM9SEEw2hJA.

Design Process

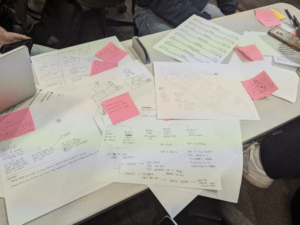

We brainstormed many ideas and game mechanics from our first meeting together. We initially explored a nautical theme and emphasized childlike wonder, adventure, and friendship. We set the environment to be a container ship and envisioned the protagonist to be a young child whose father, the captain of the container ship, has fallen ill and is unable to continue commanding the vessel. The child, though young, bravely takes it upon themselves to navigate the water in their father’s absence. As with any child, they are initially naive and curious, but slowly gain experience and knowledge as they familiarize themselves with the ship and its workings. Though our team was inspired and excited by this starting narrative, our narrative will continue to drastically develop along with our puzzles.

Group Brainstorming

With a container ship as the setting, our game offered players an opportunity for a unique and exciting adventure that would be difficult to replicate elsewhere. The vast size of a container ship will provide a sense of exploration and discovery for a young protagonist, while the challenges and obstacles of navigating the unpredictable ocean can create a sense of urgency and danger. Additionally, the young protagonist could learn about the workings of the container ship industry and gain valuable life skills, such as problem-solving, teamwork, and resilience, through their experiences on the ship.

Even in the stress of the moment in game play, we aimed to retain a sense of childhood curiosity in the actions that players must take. They may be prompted to try to meet different animals or solve different puzzles that keep the feeling of the game light even in the larger, more stressful context.

Furthermore, by incorporating adventure into our game, we hope that players will be able to explore the vast and exciting world of ships, facing challenges and obstacles as they traverse the high seas. This will provide a thrilling and immersive experience, allowing players to truly feel like they were transported into a container ship. A similar experience can be had while exploring the mysteries of the ship itself.

From the beginning, our intended target audience for this project was:

- Those with an unquenchable thirst for adventure.

- Those who yearn to feel that sense of childlike wonder, where mystery and discovery lurked behind every corner.

- We hope to leverage these feelings and desires in the game we create, exploring a new setting that still is rooted in reality!

The aesthetics and types of fun we strove for were discovery, challenge, and narrative. These ports of call guided us through the project. From the values of friendship and children, we strengthened elements of family and bonding by embedding this narrative in further iterations.

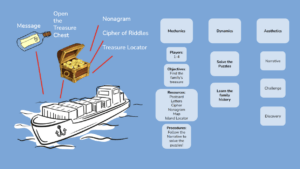

Model Map with MDA

Testing and Iteration History

Playtest Summary

We conducted 3 full playtests and 8 partial playtests that focused on solidifying our individual puzzles.

Early Iteration

Early on in our design process, we wanted to consider how we could use space and movement to create the atmosphere of a ship on the ocean. We experimented first with ideas of having a human-size board game where movement occurs in steps around the room. In this phase, each player represents a ship where a new ocean-related prompt is given at each turn and players must react accordingly. We had trouble with this version of the game achieving the narrative aspect of the game since the feel was more like a chutes-and-ladders or other board games that aren’t narrative-based. From there, we experimented with the idea of creating a game similar to True American that utilizes large movements and communication between players. However, once again, we had trouble achieving a narrative feel and establishing puzzles that were complex enough for the project parameters.

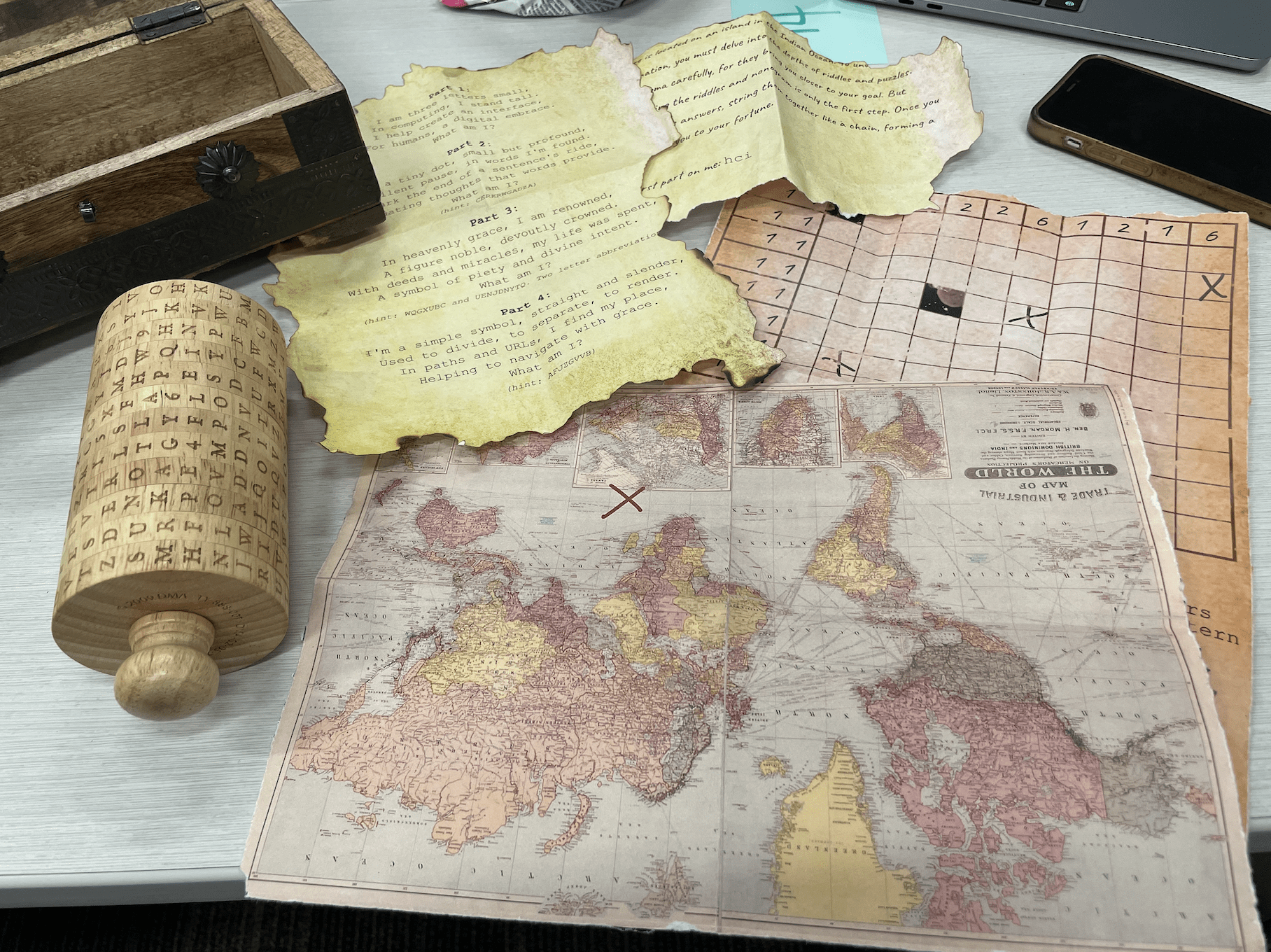

Ultimately, we realized that the best way to integrate puzzles and narrative was to create an escape room, as the teaching team had nudged us to do. So, we began by each creating a puzzle of a different style around the general narrative of someone trying to find their family’s hidden treasure. We developed a set of riddles, a cipher puzzle, a nonagram, and a digital navigation puzzle. We then figured out how to tie these puzzles together to form a narrative. The first full iteration of the escape room is summarized below.

- Solve three riddles to uncover the combination of a lock on a box

- Find a map in the box and use it to solve a digital guess-and-check puzzle that uncovers the coordinates of the island that the treasure is buried on

- Solve a nonogram that uncovers the specific location of the treasure on the island

- Decode using a cipher a message that was communicated to you by a beast guarding the treasure

- You’ve reached the treasure

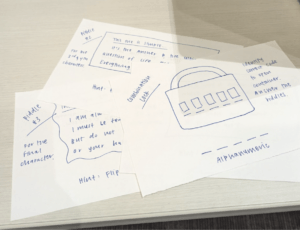

Paper Prototype of Opening Riddles

From this version, we conducted our first playtest in class with low-fidelity paper prototypes. Shana, our TA, completed the opening puzzle, the map puzzle, and briefly tested out the nonogram puzzle.

Playtester: Shana

There were a few key findings we uncovered from this playtest:

Puzzles Need a Single Solution

In our opening puzzle, we presented Shana with a riddle in the form of a poem that describes California. This should have given her the letters ‘CA’ for the first 2 characters of the 5-alphanumeric combination lock. However, Shana first guessed the letters to be ‘LA’ which was quite close to our solution, and it made perfect sense with our riddle as well. She eventually figured out that it was ‘CA’ but only after our hint which tells her that the solution is a US state. As a result, we need to revise our riddle to be a bit more specific so that it only has one solution and does not require the player to use a hint to get to it.

Limiting the Need for External Knowledge

In our opening puzzle, Shana also had to know the “Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, Everything”. The answer is ‘42’, but the only way for the player to get this reference is to have heard about or read the book. Furthermore, while searching for the treasure island in our map puzzle, Shana needed a hint, and the hint given to her was “The island contains the first name of a famous director”. Similarly, for this hint to be helpful, Shana would need to know names of famous directors, which she did not. Therefore, we need to ensure that players can crack the puzzle under the assumption that they have no external knowledge whatsoever.

Nonogram is Too Difficult and Long

Shana only briefly tested the nonogram because it was too difficult and long. Nonogram puzzles have a bit of a learning curve to new players and having to overcome this curve combined with having to crack a complex nonogram puzzle could be too time-consuming. As a result, we needed to discuss how long we want our overall game experience to be and how to adjust our nonogram accordingly.

Tying the Puzzles Together

After Shana playtested, we considered further how we can fit the puzzles together so that each one leads to the next. The first aspect we massively redesigned was the nonagram which we decided would be a good way to lead the players to the digital portion of the game, via a QR code that is the solution to the nonagram. We began with a large 27×27 QR code puzzle that took multiple playtesters outside of our group hours to complete (and some didn’t even finish after making a mistake midway through). We managed to simplify the QR code to a 21×21 grid which still required about an hour for playtesters to complete. We felt like we ran into a dead end with simplifying the QR code into a nonagram that players could complete in less than 20 minutes, so we decided instead to create a short link for which the nonogram would reveal the link extension. This made our puzzle shrink into a much more manageable 10×10 puzzle that players could individually complete within 15 minutes.

We playtested this final version of our puzzle one last time with one playtester, who appeared to have a great time throughout the entire puzzle. He did require some hints and explanation of how the puzzle worked, but from then on, the logical deductions came easily and he was able to solve the puzzle in about 10-15 minutes, which is what we were aiming for. In the final version of the nonogram, I added some written explanation on how to solve the puzzle to mitigate the need for a verbal explanation.

Playtester: Stephen

Integrating the Narrative

After playtesting and solidifying our opening riddles, we decided that it was time for us to better incorporate a narrative to get the players excited about cracking the puzzles and winning our game. From the very beginning, we wanted to frame our game around a ship theme, so we brainstormed narratives that would incorporate this evocative theme yet still make our game distinctly unique from every other buried treasure adventure out there. Ultimately, we decided to leverage the emotional connection and investment that comes from family.

As we considered how to better tie the narrative together, we determined that it made the most sense for all the puzzles to be set in one location to maintain the players’ suspension of disbelief and immersion in the game. So, we adjusted the general outline of the game to be the following:

- Solve three riddles to uncover the combination of a lock on a box

- Uncover additional riddles in the box that reveal to you the beginning of a link. Hints can be decoded using a cipher

- Solve a nonogram that reveals to you the end of a link

- Use the link and a map in the box to solve a digital guess-and-check puzzle that uncovers the coordinates of the island that the treasure is buried on

- You’ve found the treasure

To better incorporate the narrative, we adjusted the puzzles to be in Sebastian Riddleton’s letter and included artifacts and hints that players can interact with for a more interactive, immersive experience. In our glass bottle attached to the locked treasure chest, we include two letters. One was written by Explorer Sebastian Riddleton in 1980. In his letter, Sebastian addresses his son Alexander Riddleton and reveals that he is secretly a master puzzlemaker. He wants Alexander to share his passion and embark on a puzzle adventure, one that ultimately leads to a buried family treasure. Sebastian ends his letter with three riddles that will reveal a combination code that can unlock the treasure chest and wishes his son luck. The second letter was written by Captain Alexander Riddleton, Sebastian’s son, in 1997. In his letter, Alexander addresses his daughter Sage Riddleton in a state of urgency. He is on a rapidly sinking ship and writes to inform his daughter about his father’s enigmas that he failed to solve. We have also included other artifacts in the glass bottle that Sebastian’s opening riddles cannot be solved without. From the contents of the glass bottle, it can be assumed that the players must take on the role of Sage Riddleton and now have an incentivizing objective to solve the puzzles and find their family’s hidden treasure.

Developing the Cipher Riddle

Creating a cipher riddle was an intriguing and challenging journey that required numerous iterations to reach its final form. It began with a simple idea to craft a sea-themed riddle, but eventually evolved into a multi-faceted puzzle that engages the participants in deciphering hidden messages.

Initially, the cipher riddle started as a generic, multi-versed poem with the answer being “a shark.” The primary instruction we had given ourselves was for the riddle to revolve around a sea theme, leaving the form and complexity of the puzzle open-ended. This initial version served as a foundation upon which subsequent iterations would build.

As we reviewed the initial version, it became apparent that a single poem with a straightforward answer lacked depth and engagement. It also was only vaguely relevant to our overall narrative. We wanted to challenge the participants further and create an immersive experience. Therefore, the next stage of development focused on expanding the riddle into a series of interconnected poems. Each poem would present a clue or hint that, when concatenated, would eventually reveal a part of a link, which would lead to the final challenge.

This evolution allowed us to incorporate layers of complexity into the riddle. Participants would need to analyze each poem, identify the underlying hints, and piece them together to unveil the hidden link. The iterative process of crafting these interconnected poems involved revisiting the original sea theme and brainstorming various angles to create intriguing clues. We considered different poetic forms, such as haikus, sonnets, and free verse, to add variety and maintain the participants’ engagement.

After several changes, we arrived at the final form of the cipher riddle—a set of four riddles presented in plaintext, but with the hints encrypted using a cipher. This approach added an extra layer of challenge and excitement to the puzzle. The participants would need to decipher the ciphertext hints to unlock the clue contained within each riddle.

To encrypt the hints, we explored various ciphers, including the Caesar cipher, Vigenère cipher, and substitution cipher. Each cipher offered its own set of advantages and limitations. We decided to include a physical cipher wheel in the chest, which adds a degree of convenience and suggestion. It also balances difficulty level, ensuring it was solvable with some effort and deduction. The wheel did not use the Caesar or Vigenère schemes, and had its own algorithm.

Cipher

Throughout the process, feedback from early playtesters played a crucial role in refining the cipher riddle. They helped us identify potential pitfalls, ambiguous wording, and areas where the difficulty level needed fine-tuning. For instance, we found that encrypting all the text in the riddles was extremely tedious. We continuously revised and polished the riddles, considering the feedback and striving to strike the delicate balance between challenging and frustrating.

By evolving this stage of the game into a series of interconnected poems and encrypting the hints with a cipher, we achieved a challenging yet engaging experience for the participants. This journey involved refining the riddles, selecting suitable ciphers, and incorporating feedback to create a final product that was both enjoyable and intellectually stimulating. Crafting the cipher riddle highlighted the importance of iteration, creativity, and thoughtful design in creating an immersive and captivating puzzle.

Fine-Tuning the Digital Puzzle

In early playtesting, we prototyped our digital puzzle as a Google Sheet, where the objective is to identify the correct coordinates of the treasure based on an “X” marked on a map. Using this prototype, we validated in early playtesting that this puzzle was engaging, so we decided to refine it to be more integrated in the narrative. We decided to create an HTML site with a design and user interface that gives the emergent vibes of a ship radar and navigation screen. This meant that we could incorporate it into the narrative as the navigation system of Alexander Riddleton’s ship that has the treasure location programmed into it. Another improvement was creating a more intuitive and user friendly confirmation screen when the player finds the island in the Indian Ocean.

After developing the narrative arc of the game and backstory, we playtested to see how it affected the experience solving the riddles. This playtester was very invested in the lore of the game and finding out the family history including the history of “the ol’ man and the treasure of the mother.”

Playtester: Matthew

Final Playtest

Two people, Jasmine and Sreya, played our game during the last lecture, and the final playtest is recorded here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cM9SEEw2hJA. They bounced back and forth, looking between the various pages of information provided as a part of our game and discussed with each other what they thought the answers to our riddles and the puzzles were. The game, although it can be completed by one person, works best in a group environment, where all members of the group can solve the puzzles collaboratively. They were able to complete our game in about half an hour, the quickest one yet.

Conclusion

Overall, our team is incredibly proud of the progress we have made on Riddleton’s treasure over the span of ten weeks. All of our playtesters have thoroughly enjoyed our adventure game, finding it to be both challenging and a fun temporary escape from reality. We are thrilled by the positive feedback and are excited to share our creation with the teaching team, knowing that we have crafted an engaging, unique experience that offers players an interactive challenge and a chance to immerse themselves in a thrilling world of puzzles and treasure hunting.

Pictures of our Final Treasure Hunt Game!

Artifacts Inside Treasure Chest

Birds Eye View of Open Treasure Chest

Glass Bottle + Locked Treasure Chest

Important Links