Game: Florence

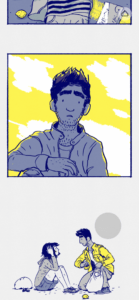

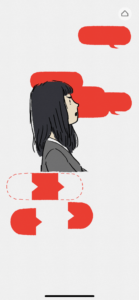

This game felt like a work of art. It wordlessly drew me in and, unknowingly, had my eyes brimming with tears. I particularly loved the aesthetics of the game, particularly the line-drawing style of the entire game. The color choice is perfect, with shades of orange, teal to deep rose-red to signify the progression of the relationship, and the use of deep red and jagged edges of speech bubbles for arguments.

The various uses of colors and shapes in the scenes and puzzles.

The game is interspersed with many minigames, paralleling/mimicking Florence’s thoughts and actions and advancing the plot forward. The difficulty of the puzzles is generally minimal but parallels how challenging the action was for Florence. For example, as their relationship progresses, Florence becomes more comfortable talking with Krish and the speech bubbles’ puzzles become easier. However, the hardest one for me would have to be piecing together the drifting fragments of the scene of their last hug as they break up, as I think the game makes it intentionally really difficult to emphasize the emotional weight of this scene. I took probably 3-5 minutes to finish this puzzle.

The whole game exists without dialogues. Music is used as a substitute for words/dialogue throughout the game, with the cello representing Krish and the piano following Florence. The music in the background also complements the narrative: the soothing and lovely melodies during their romance, and the dissonance and sharp noises during their emotionally-fraught arguments.

I will be commenting on the feminist themes of the games in terms of the game narrative and mechanics. The bracketed page numbers refer to the page numbers in the reading assigned ‘Play Like a Feminist’.

In terms of the narrative, the game’s overall narrative has a strong feminist theme, anchored by a central female protagonist who evolves during the course of the relationship, recovers from the dissolution of a relationship, and eventually finds her own path in life. I felt that it indeed is a feminist story as it is ‘conversational, personal, and relays narratives that surpass the expectations we tend to have of those ushered in to and for patriarchal audiences’ (p. 96). I agree that it is intensely personal, and captured the sentiments of a stage of young adulthood perfectly.

Another feminist narrative aspect of the game is its potential for ’empathy building’ (p. 97). I found myself able to emphasize with Florence deeply and felt that I was living vicariously through her through the simple scenes in the game. A scene that most moved me was Florence re-arranging the house when Krish moves in— deciding what items of hers to move to storage to accommodate Krish’s possessions – it gamified and made into art an act so common in cohabitating relationships, for the first time led me to recognize the beautify and significance of this act. And the corresponding scenes of moving out are heart-breaking to go through.

In the moving-in scene, arranging Krish’s belongings into their shared space and deciding what items of theirs to move into the storage box to accommodate his things. Agency is created here for players as they can control how much Florence changes her set-up (and storing away her items) to accommodate his new things.

In the corresponding moving-out scenes, players remove Krish’s belongings from the shelves to the moving-out box.

Additionally, I felt that the game was able to exist in the ‘narrative middle’ by not being ‘climax-centric’, a shift away from the ‘heterosexual masculine perspectives’ dominating video games. I didn’t think there was a recognizable climax in the game, as each chapter was equally as significant, contributing to the coherent whole of the narrative.

In terms of the mechanics, I feel that there is less player agency in the game, as the game adheres to a set flow with minimal deviations possible. However, the mini-puzzles did successfully help to establish some agency, requiring input from the players to advance the plot forward. For example, in the moving-in scenes, a sense of agency is created here for players as they can control how much Florence changes her set-up (and how much of her items to store away vs. Krish’s) to accommodate his new things. I agree with the reading that “true agency comes on the back end of the process: interpretations and fandoms embody the real kinds of agency that a player can have in a game” (p. 103). It is the interpretation of the game that has the potential to create agency, as the game could be an effective medium to empower players in processing and making sense of their own relationships in their own lives, in both their formation and dissolution. It could be an effective ‘agentic-training tool’ (p. 101)

Points of agency in the game also include whether to pick up Mom’s phone calls (spoiler: she will continue calling until you pick up and there is no way to advance the plot without picking up), and various chat response options.

Warning – there are additional costs of the game beyond the listed purchase price on the app store: it made me finish an entire box of napkins.

Discussion question: What would you add to/modify about the game mechanics to make the game mechanics more feminist?