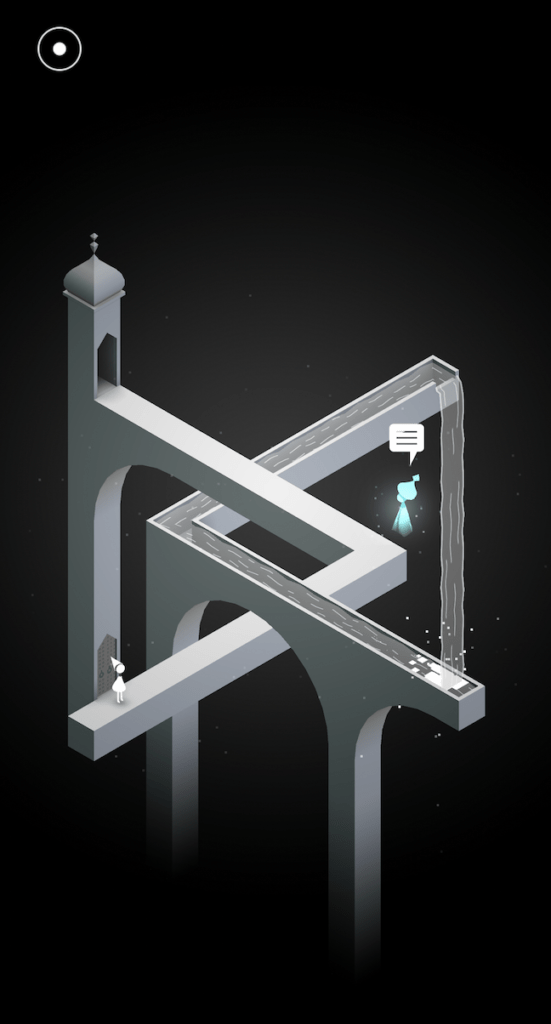

For this week’s critical play I played Monument Valley. It was created by Ustwo games, is available as an app on Ios, windows, and android, and is playable for anyone ages 10 and up. This game is all about solving aesthetically pleasing puzzles so that the main character, princess Ida, can restore the geometric pieces to these puzzle monuments that she apparently stole. These aesthetic puzzles and their mechanics heavily influence the types of fun that this game elicits.

The first mechanic of these puzzles is that they are all towers with simple pastel colors and optical illusion properties. Even though they all share very similar architecture, each one has its own puzzle theme. The fun is in discovering these new themes to unlock higher levels. Some towers require you to spin a lever, some you can drag small pieces around, and others you can completely spin to totally change the orientation. I would call this a challenge, but you must really examine the tower for a bit and swipe your finger around in order to actually figure out what the missing moveable piece is.

The challenge type of fun comes once the puzzle theme is figured out. Most levels have a loop where you get a “training” tower that helps you figure out the puzzle theme, then you get to a relatively much harder puzzle, then you get to the final one which is usually the most beautiful architecturally but not as hard as the second (some levels have more or less but this is the general game architecture). The challenge is using the tools in the easier towers to figure out the more challenging towers.

What keeps a person engaged with this challenge, to me, is the subtle background narrative this game tells. I cannot decide if the narrative can actually be put into the narrative category or if I want to label it as expression(?). In the beginning, Ida meets this ghost that asks her a few cryptic questions about why she comes back to the monuments, leaving the player feeling desperate for more information. This place is beautiful and peaceful, but Ida seems to be a low key antagonist, so this peacefulness also kind of feels like emptiness. I think the emptiness spurs the player to want to find out what happened here, and the limited information provided acts like a mysterious lover who you do all this work to get to talk to you who then all of a sudden disappears until you finally get to the next level. I am not sure if that makes sense. It is like wanting what you can’t have, and the more tiny teases of information the game provides the more dedicated to figuring out the puzzles you get. In this way, there actually is not that much narrative, but the feeling of desperation I had I felt was maybe a manifestation of my own emotions that I would lump into the category of expression.

The other mechanic that adds to the effect above is the pace of the game. Ida walks pretty slowly, and there is no timer that requires you to figure out puzzles fast. If you are like me, you are trying to quickly figure out the way each geometric shape matches up to get to the next part of the story. Despite my fanaticism, because this pressure was not actually enforced by the game, I was never stressed to reach the next level. I was actually able to enjoy my failures and my moments of realization on my own time. Usually slow pace games annoy me, but the pace of Monument Valley actually ended up perhaps making me less annoyed than I would have been otherwise.

In all, I really enjoyed playing this game. The slow, beautiful and soft mechanics of the puzzles really add to the experience of a peaceful “struggle” of figuring out each level.