Life is Strange 2 is a walking sim/mystery game made by DONTNOD Entertainment and Feral Interactive, and published by Square Enix. It’s available on consoles and Steam. I played the first episode. Spoiler alert btw.

Exposition: The story begins with Sean, a 16-year-old high schooler from a working-class family, dealing with the most stereotypical high schooler stuff, including preparing for a party, stressing over a girl he likes, and dealing with his 9-year-old little brother Daniel.

Inciting incident: Halloween is coming up, and Daniel has created a concoction of fake blood. He’s playing around and accidentally spills some fake blood on his racist asshole neighbor, and Sean steps in to defend Daniel. Things escalate, Sean beats up the neighbor, and a police car pulls up. Seeing the situation (of a bunch of fake blood on the neighbor’s shirt), the officer pulls out a gun and demands Sean and Daniel to freeze and get down on the ground. Hearing the ruckus, their dad runs in, and everyone is panicking and the officer shoots their dad.

The twist comes when Sean next opens his eyes, the police car is flipped over, the officer is dead, and overall it looks like this place was struck by a tornado. Not knowing what happened, Sean was either unsure of his innocence or figured he/Daniel would inevitably be framed as the perpetrators, so he decided to run away from home with his (then unconscious) brother.

And so the mystery begins. It’s a bit of an unconventional mystery—from my perception, most mystery stories involve discovering the secrets of some creepy place, shady person, or past event. In this case, the mysterious event happened right before our eyes (for fractions of a second), and we’re trying to understand what really happened. So the mystery is more about somehow gaining an understanding, a job purely for the narrative, rather than being able to use game mechanics like discovering clues and solving puzzles.

Struggles: The death of their dad places a huge emotional burden on Sean. The burden is made tenfold by the fact that Daniel doesn’t remember the officer shooting Dad, so Sean is forced to lie to Daniel to not also give him the burden, which could be a disastrous thing to do when they are still on the run. In addition, it’s unspoken but I could feel that Sean now has full responsibility for taking care of Daniel for the first time in his life, which is quite challenging materially—given their lack of food, shelter, and money—as well as emotionally—having to repeatedly comfort Daniel, tell him everything’s going to be alright, and pretend that they are just going on a hiking trip that dad couldn’t come on, while also not having any concrete plan of how they’re going to survive or where they’re going to go.

Pictured: Story games seem to go well with aesthetically pleasing scenery. Among all the humanly chaos, the serenity of nature is still there.

Given this is a narrative-driven game, it is expected that there are practically no interaction loops and lots of interaction arcs that exist over the course of the episode. This is primarily because the framework of an interaction loop assumes that the player has something to learn, when there is simply nothing to be learned—there is no mechanical skill involved, and there is no single “right” way to play the game. Moreover, you don’t have the opportunity to revise any of your decisions (without starting a new game or reverting to a previous save), which has the benefit of creating a sense that your actions have consequences and meaning, but also prevents any iterative learning. As mentioned in the reading, interaction arcs are great for content that can only be played once, and the overall game is formed by a sequence of arcs.

Here’s an example of an interaction arc in the episode. Model: UI elements that display some actions that can be done, such as buying food, shoplifting food, examining objects, talking with people, etc. Action: do the action that you choose. Rules: how people respond to your action, such as whether you successfully shoplifted, or how they respond to the things you say. (Perhaps rules and feedback are kind of blended, since there are no strict rules where it’s obvious what the consequences of an action is.) Feedback: a continuation of the narrative based on your action.

Pictured: More pretty scenery. Reminds me of Firewatch, also a mystery/walking sim game located in a forest.

At some points in playing this game, especially when Sean’s struggles were most intense, I really wondered who the target audience was, what type of fun they were having, and who in their right mind would play such a game—for better or worse, most players probably empathize with Sean, and I doubt anyone needs a fictional character to take up their emotional energy. Ok, I’m definitely wrong because we love stories, and stories that captivate our emotions tend to be the most immersive. However, from what I’ve played so far and seen from the trailers, this is a game that throws boulder after boulder at Sean, a nearly non-stop stream of bad news, unfortunate events, and trouble with Daniel, with lucky breaks few and far between. In our American culture, we tend to like stories where the protagonist is ultimately justly treated or finds new meaning in life, such as in The Shawshank Redemption. Maybe Life is Strange 2 is still such a story, just a painfully long one.

All in all, I think the most prominent type of fun is expression. The game very explicitly emphasizes player choice matters—it can make the difference between you getting into trouble or not, your little brother being happy or not, etc. I tried to do another playthrough with some of the opposite options to what I chose on the first run and disappointingly, it seems like narrative-wise player choice doesn’t actually matter that much. However, in my first playthrough, I was fully under the impression that player choice mattered and I thought through each choice carefully, so I would say the illusion of choice was still successful. Other than expression, narrative is obviously what makes the game captivating though also potentially stressful/painful, and there are minor and rather artificial elements of challenge and discovery that are embedded within the narrative.

This type of expression is very different from creative expression, however, but more like moral/decency/values expression. To make certain choices in the game, such as between begging/stealing or paying, or between fighting or attempting to escape, is an expression of the player’s values. Perhaps one player views such extreme behavior as justified for the protection of Daniel, perhaps another player views such behavior under a categorical imperative. To be capable of such reflection and expression, I would say the corresponding target audience is around 16+.

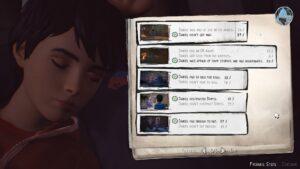

Pictured: Interestingly, at the end of the chapter, the game gives you a breakdown of all the choices you made/consequences, along with a percentage which I assume is what percentage of players achieved that outcome. There are no right or wrong choices in this game, so this is merely an interesting comparison.