OMG 😱 I’m in total disbelief right now about how good this game is at questioning the role of a player in a narrative experience, and in general breaking so many genres (and beyond genre) conventions such that I had to consciously question every action I was taking.

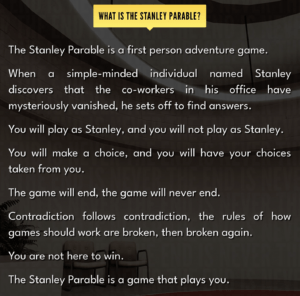

From their website, this sums up the spirit of the game pretty well:

[Spoiler alert] At the start of the game, you get this brief exposition about Stanley and the situation he’s in—where did all his coworkers go? On this surface, this seems like another Firewatch (who/what/where did X do/go?), but it quickly becomes apparent that this is actually a meta-story. There’s a Narrator narrating the story of you, while you’re performing the actions of the story of you. In certain places, you are faced with a choice to obey or defy the Narrator, and I’ll talk more below about how that makes the game really interesting.

There’s a lot of relevant commentary and reflections this game makes in regards to our reading on game narratives, and perhaps also some engagement with broader philosophical concepts like free will, but for the sake of the critical play, I’ll focus on the questions first.

Basic info

The Stanley Parable (I got the Deluxe Edition but the first part of the story is basically identical) was made by an indie studio spearheaded by two writers/designers, Davey Wreden and William Pugh. It’s available on Steam and consoles. The game is trivially accessible to a wide target audience (just hold W), but I would say it’s really targeted towards and can only be appreciated by experienced gamers (need to know a genre to realize it’s been defied), philosophers, and writers.

Formal elements

As aforementioned, it’s a first-person single-player game where you play as Stanley. Other than that, the objectives, outcomes, rules, procedures, resources, and boundaries are all intentionally repeatedly questioned, and that’s what makes the game so mind-boggling.

The objective starts out as discovering what happened to your coworkers, but then there’s this period where the rules, procedures, and boundaries are modified several times, and it’s really not clear what’s going on anymore. What does become apparent in this period is that the game is about your relation to the Narrator, and how the narrator dictates your objectives (which you can choose to follow or not), dictates the outcomes (based on your choices), and to a lesser extent also the rules (such as when the timer is created).

In a walking sim, perhaps resources could be generalized to “progress”—after all, any item you get in a walking sim isn’t going to have any purpose other than to progress the story. The Stanely Parable also has a really interesting take on progress. For various story-based reasons, the Narrator sometimes resets your game so you start at the beginning again. There are two senses of progress: 1) you know you’ve learned from your past runs like Outer Wilds, but also very interestingly 2) the Narrator knows what you’ve learned from your past runs. There is very clearly auto saves going on in the background, as evidenced by how the Narrator will give you new voice lines that build on prior knowledge, but every time you play, the button reads “New Game.” This also breaks the conventional magic circle of a video game, where everything you’ve done in the game is potentially part of the magic circle, rather than typically everything within your save file is part of the magic circle.

Types of fun

The types of fun it involves definitely include narrative, discovery, and perhaps even expression.

The narrative is obvious—walking sims use minimal gameplay interactions to tell some kind of a highly structured narrative. Even though the narrative is highly structured, it is very locally non-linear through the well-timed uses of player choice.

The type of choice involved is whether to obey or defy what the “Narrator” says you are doing. To always obey is to not explore and discover, and at least for me, I always tried to do the “wrong” thing first until it seemed like a dead end. This is me as a player building a mental map of the game world, as described by our reading today.

Herein also lies a very unconventional form of expression—the desire to assert that you as the player have free will. This desire is very natural due to the aforementioned odd dynamic between you as Stanley and the Narrator, where you are acting out what the Narrator says. This is the ultimate struggle of the game. In some sense, the Narrator is your villain. No matter how hard you try to defy the Narrator, you cannot win. It’s not that the Narrator won’t let you win, but more that “winning” doesn’t exist as a concept in a walking sim. As described eloquently by Narrator 2, the only way to win is to hit escape and quit.