“Hot Takes” creates a space for friends to share their inner thoughts about each other while having a good laugh! Whether the game serves as a test to see how well the players know each other, or simply as a way to playfully make funny assumptions, everyone will have the opportunity to learn more about one another as each player gets a turn seeing everyone’s responses through the creatively prompted cards.

This social game has two options for decks, Mild and Spicy. The Mild deck contains prompts that are safe for a family friendly environment, or a group of friends just getting to know each other. The Spicy deck is designed for a closer group of friends who are comfortable with more raw, honest, and out-of-pocket prompts. These decks widen the audience range, allowing for more and more to have fun and get burned!

Idea Exploration

Our chosen game concept from section was “a guessing game based on stereotypes.” With this concept, we each proceeded to brainstorm different systems either in written format or through sketches. We discussed our ideas and decided on a final idea as a team.

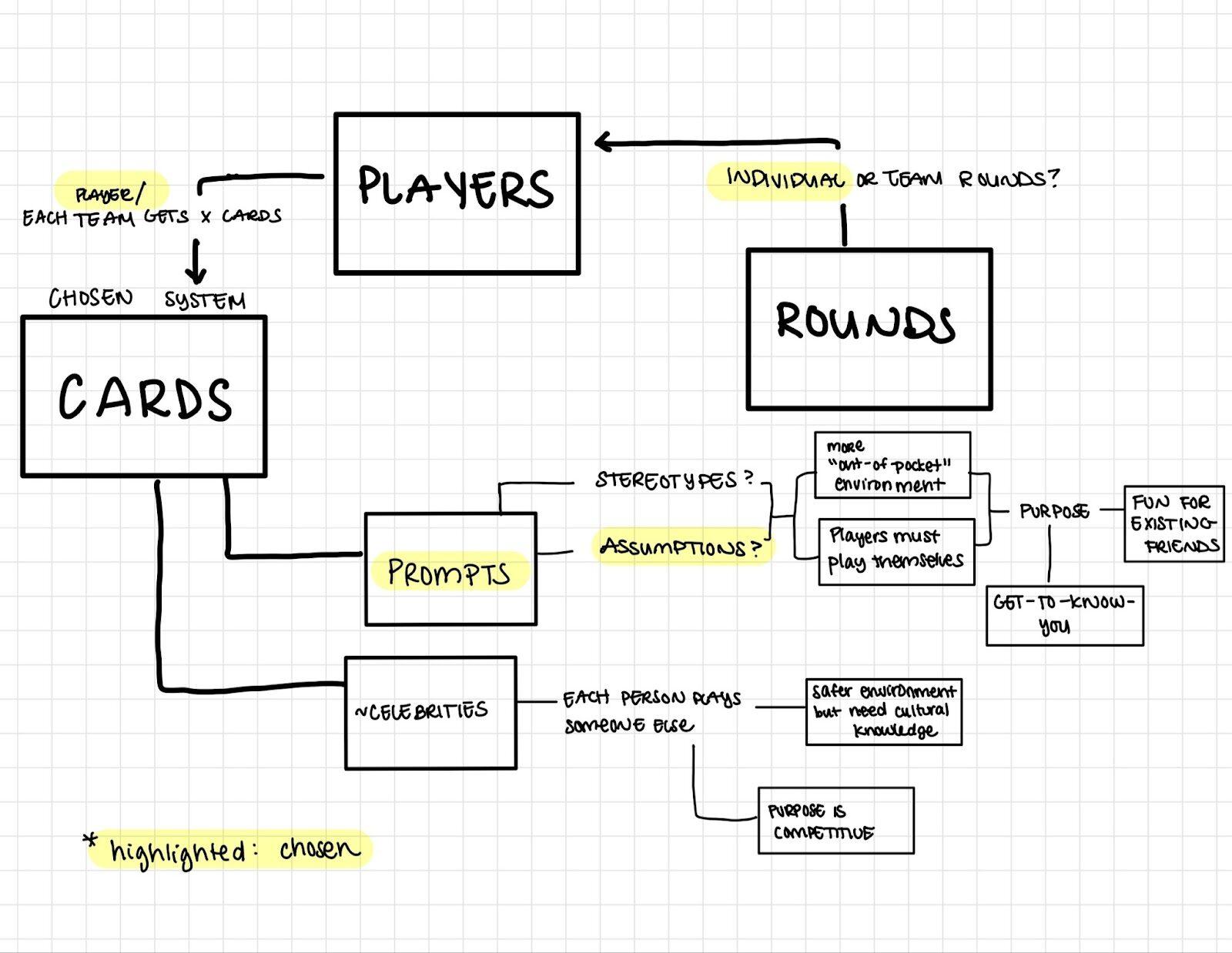

Concept Map of Chosen System

We decided to move forward with a card game for our P1. We had discussed whether or not we wanted players to participate individually or in teams, and what the cards should contain. Depending on our decision, the dynamics of the game changes. Our thought processes as well as some of our chosen mechanics are outlined below in the concept map.

Initial Design Decisions

For our first prototype, we decided to move forward with mechanics similar to Apples to Apples or Cards Against Humanity. We liked how these games are able to elicit heated discussions between people, whether they are a well-established group of friends or strangers that had just met. However, we felt that these games are somewhat impersonal and abstract, so we wanted to design our game such that people learned more about each other, and perhaps what others think of them as well. To do this, we created cards that contained various superlatives, such as “most likely to eat food off the floor.” Gameplay begins with each player being dealt 5 cards and selecting one player to begin in the “hot seat.” Much like Card Against Humanity, each other player gives a card discreetly to the player in the hot seat based on what the other players think applies to that player the best, and after shuffling, the player reads each card out loud and selects one that they think represents themselves the best. We thought this would create interesting dynamics between players, fostering social fellowship. Even if a player takes slight offense to a card or thinks it doesn’t represent them, the players could talk it out and learn more about each other and how they are perceived. Play would continue with each player replenishing their hand to a full five cards and rotating the hot seat so everyone gets a chance to be in both roles. Our hope was that players being on both sides of these interactions would open the door for reciprocity, so if one player received a card that they didn’t like, they could return the favor later. By creating a lighthearted atmosphere where players interact with these different roles, we hoped to create opportunities to build trust and rapport between players, and maybe lead to increased disclosure once players feel more comfortable with each other and the flow of the game.

Our target audience with this initial prototype was quite broad. We thought that anyone from complete strangers to good friends could play, and even though the dynamics might be different between these populations, the game could be fun and achieve our goals of building friendships in both settings. Keeping this in mind, we included a variety of superlatives, from more risky (most likely to start a fight at a party) to more benign (most likely to befriend a celebrity). If a player didn’t feel as comfortable with a perceived attack on someone’s character that they don’t know well, they would hopefully have enough cards in their hand to pick a more benign card, and vice versa. We also wanted to appeal to expression, so we included some blank cards to allow players to write in their own superlatives that could apply directly to other players. We didn’t really set an end to the game, but we loosely established the framework that the player that gets the most cards by the time play is stopped would win. This was another mechanic cannibalized from the Cards Against Humanity framework, appealing to challenge, but in our initial prototype, we decided to emphasize this a lot less, since we cared more about building community than making winning players feel exhilarated and losing players feel bad.

Testing and Iteration History

We play-tested several times, both inside and outside of class.

Iteration 1: Initial Prototype Playtests

First Playtest – In class (4/18)

For our first playtest, we playtested our first prototype (see above ‘Initial Design Decisions’ for details) with the design team and 4 members of another team in class. Our initial prototype consisted of a single deck of cards with responses along the lines of “most likely to…”, along with some blank pieces of paper that functioned as “blank cards” for users to put in their own responses. Our original card deck can be found at the following Google Drive link.

What worked:

- People seemed to like the prompts– there was laughter whenever the judge read out a card.

- People found the rules intuitive and easy to learn

What didn’t work:

- Rounds were very short; judges would read the cards, pick the card, and the round would end. There wasn’t any discussion involved.

- Players were hesitant to play some of the more objectively negative cards (one specific card mentioned was “Most likely to be a serial killer”) with people that they weren’t friends with

- We initially asked players to advocate for why their cards should be chosen, but we ended up changing it to having players play the cards anonymously after players indicated that they’d prefer to not have to publicly play cards.

- We received feedback that anonymity made it easier to be more “out of pocket”

The emergent game dynamics we observed were not what we envisioned when initially creating our prototype– we had envisioned that the cards would generate discussion among players and enable them to learn more about each other, fostering social fellowship. However, we noticed that players were hesitant to express either the reasons why they chose cards for other players, or why they chose the cards they did when they were judges. Players were also quite hesitant to play some of the more provocative cards. This is likely because the level of disclosure required to do so was too high for the level of friendship this group had. The desire for anonymity players exhibited highlighted how players might have felt too vulnerable to be able to open up to each other. As such, the emergent game dynamics did not encourage social fellowship and friendships at all, as interactions between players remained brief and infrequent.

We decided to test out the prototype with different friend group dynamics rather than a group of unfamiliar players to see if there was a difference in the game dynamics.

Iteration 2: Testing with different friend group dynamics

Playtests with Regina, Maxwell, and Jennie (4/19)

These playtests were short, involving an existing group of friends, and were mainly intended to get some insights into whether existing friendships between players would influence the game dynamic.

What worked:

- Players were able to take each other into account when playing cards; there were several remarks along the lines of “I think this fits you” when referring to cards in the players’ hands

What didn’t work:

- “Potential for savagery”

-

- One player mentioned that in similar games like Cards Against Humanity, even if cards are “mean” or shocking, they’re not necessarily directed at the player, so players take less offense

- Tone was wildly inconsistent among some of the cards

-

- “With friends who roast each other, all of the cards could be more savage, but if it’s for getting to know people then the tone should be different.”

- Unclear what the aim of the game is, lacking objectives

Based on ideas from “Game Design Patterns for Building Friendship”, it is likely that the level of unpredictability in tone on the cards was hampering reciprocity– this suggested that we should either tone down the provocativeness of our cards, or pivot to change our audience to players that have some level of familiarity and friendship with each other instead of targeting players who were getting to know each other. The nature of the cards are intended to modify the dynamic of the game depending on the level of intensity. However, we learned from this iteration that in our context, the dynamic should be stable and stay consistent to the audience’s desired dynamic.

Playtest with Jeong, Emily, and the design team (4/20)

This playtest was conducted in class and involved 1 student who didn’t know the rest of the group, and 4 students who knew each other beforehand. One new thing we did before this playtest was to ask the players how “spicy” they wanted the game to be and separating the cards of our additional prototype into 3 different levels of humor based on how provocative they were. However, the players wanted to use all the cards, so we played with all the cards as in previous play testing rounds.

What worked:

- Players were bantering with each other a lot– there were a lot of sustained interactions between players, especially regarding the card choices

- Players played certain cards with the judge in mind

-

- One player said “I feel like this [card] is a good vibe for you” when playing a card for another player.

- Players also reacted much more when reading the cards other players submitted for them

-

- There were a lot of times when players disagreed with cards (and sometimes explained why)

-

-

- For example, one player received a card saying “Most likely to cry during a horror movie” and commented “That’s not true, I love horror movies”

-

-

- One player even mentioned that she felt complimented when reading a card

- The one player who didn’t know anyone else in the game beforehand felt that it was fun to see what other people chose, even if they didn’t know much about the others

What didn’t work:

- One player mentioned that sometimes it seemed “more like playing the meanest card rather than the most accurate one” at times.

-

- For example, one player said “This one isn’t that fun but it’s so true [about you]” to another player, highlighting how players were thinking about how funny a card would be, sometimes more than about how much the card was accurate

Based on the insights from these two playtests, we decided to pivot our game audience to groups of friends, rather than focusing on being a get-to-know-you game for strangers. We also decided to formally test out splitting the cards into different decks for different levels of humor in the next playtest. We thought that splitting the deck into more family-friendly cards and cards with more mature themes would not only allow for groups with differing levels of familiarity with each other to play by easing up the intimacy curve, but would also help alleviate the problem of “playing the meanest cards rather than the most accurate ones” by giving players the option to separate out the “mean” cards.

Iteration 3: Splitting Decks and Adding in a Discussion Phase

Testing with Linus, Bobby, Andy

Online Prototype can be found here: https://playingcards.io/7qrnm3

In previous rounds of playtesting, we noticed that rounds tended to pass very quickly, with very little discussion between players. For this playtest we wanted to see how we might encourage more interaction between players. Therefore, we added in an additional rule– after the judge looks at each of the submitted cards, the judge should explain why they’re leaning towards picking a certain card, and then players have a chance to jump in and explain why their card should be the one explained.

We also split up the cards into a “family-friendly / mild” and “spicy” decks– the split can be found in this Google doc.

In the first round of this play test, we played with both decks mixed together (similar to previous rounds of playtesting) and tested solely the explanation and discussion phases. Here is the full video of playing with both decks (log in using Stanford Account).

What worked:

- The explanation and discussion phase lead to more discussion among players, and also gave players more of an insight into other players sense of humor or personality

What didn’t work:

- Sometimes the explanation spiraled off into long arguments about what card was best– one player suggested that perhaps a framework for discussion, like timing or taking turns, would help stop people from getting distracted

- Some of the new “spicy” cards added killed the vibe, especially if they were very negative cards like “likely to talk behind your back”

- It was hard to keep track of who won each round

We also did an additional playtest with only cards in the mild deck (unfortunately not recorded as we ran out of storage space) to see if the game dynamics changed. We hypothesized that the mild deck would provide a lower-stakes environment since the statements were generally more neutral / positive, or would have more of an opportunity to tell a story.

What worked:

- Humor level seemed to be scaled well– one player said that it was “good humor without being overly edgy”, compared to the spicy deck, which “felt like it relied a lot on shock humor”

- The game was calmer as opposed to the previous game with both the spicy and mild decks.

What didn’t work:

- For friend groups who know each other well, the mild deck might be too tame; there were several remarks that it was sometimes boring

From this playtest, we learned that explicitly adding in a space for players to discuss their choices led to more interactions between players, even if it wasn’t structured. Players ended up debating not only their own card choices but also how others perceived them, which helped increase the sense of social fellowship. This playtest also informed us that splitting the decks into two helped change the emergent game dynamics. The spicy deck seemed to work well for close friend groups (like the participants), but the mild deck had statements that required less disclosure and vulnerability, which would lend itself well for building new friendships.

Testing in class on 4/25:

Video: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NliWz2QI_6slUG_oGSHpJ_UPQV9968jf/view

Our in-class testing on 4/25 informed our final prototype with a plethora of insights.

For what did not work, the players were confused about the metaphor / branding of self-aware. They felt that the mild and spicy deck did not fit into the overarching metaphor of “self-aware”. This disconnect helped us decide on the “Hot Takes” branding / design metaphor. Alongside this, they thought that the mild deck could be coined a “get to know you” deck, which helped us solidify the content in the deck.

Regarding the contents of the cards, our play testers felt that the intensity of each card may not have matched all their peer cards in the deck. Colloquially, they felt that some cards within a deck have a greater shock factor than others in the deck. Therefore, this informed our filtering process before printing our final deck. As we’ve learned, the lack of anonymity and presence of ownership in the placement of your card means players are more careful socially, especially when they are less comfortable with the group.

At 8:26 of the video, a playtester noted that she “did not want to think of one”, referring to the blank card / generate your own assumption. In follow up questions, we understood that it felt mean to think of an assumption about someone, especially a group you did not know well. Therefore, this informed our design decision of removing the blank cards (generate your own prompt) from our game, as players felt that it was mean.

The most salient insight was about the intended audience and what kind of group setting optimized play experience. All of our players were less likely to justify their answers with people they are not familiar with. Every turn throughout the video, you can hear players apologize when putting their cards down – feeling slightly scared and anxious. Gameplay with a closer group would mean avoiding “picking the least bad one” and more playful discourse about which card they chose. Therefore, we clarified the intentions of each deck and which spicy level would be best suited for a certain group. This is grounded in what we know about building friendships through gaming in class, as the hesitation players experienced with too intense of cards means that the cycle of positive response and reinforcement is not formed; therefore, the players do not get as close through repeated actions and positive reaction loops.

Video of Final Playtest

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1o0S7EdbjU_U16c1-JA0t7INZFtee8YRm/view?usp=drivesdk

In the linked playtest video, we tested the mild deck, spicy deck, and did a Q&A with our participants about their experience with Hot Takes. Hence, the 25 minutes of content.

On the positive front, our playtest iterations attested to our intention of easy onboarding and learning the game, as this is a party game. There were little to no confusions about the mechanics of our game, including everyone placing their card down for each person and taking their card back to symbolize a point. The similar mechanics to common party games like “Cards Against Humanity” and “Apples to Apples” contributed to how quickly users were able to pick up on the rules. Also, we saw our random group become more friendly and familiar with each other as the playtest progressed, contributing to our aesthetic of social fellowship for Hot Takes. We repeatedly saw a dynamic of natural and playful conversation that creates that social fellowship aesthetic, meaning a strong execution and understanding of MDA structure embedded into our game. We also learned that reciprocity and trust help build friendship patterns in games, hence the offer -> friendly response feedback loop of our mechanic design allows shared social norms to be formed. At 6:58, a playtester said “I feel that this is appropriately spicy” when commenting on everyone having fun and getting to know each other. Therefore, we saw an increased comfort level during the spicy round as the game went on and they had shared time together.

For potential areas of improvement we noticed during playtesting, there are a few worth noting. Instructions explained to advocate for the card you put down, yet the players did not want to follow this norm. Additionally, players noted that “This is a story on its own” referring to all the cards they received together. However, we discussed this potential idea (the cards forming a story together) as a team and felt that it did not support our vision / gameplay we intended. One other suggestion we received from the playtesters was that points should be awarded to which cards the judge agreed with, rather than just the “best” card, as oftentimes there were more than one card they liked. However, we felt that might make the game more complicated, and decided to keep the rules as is.

Iterations of Visual Design

Our full design mockups can be found here:

https://www.figma.com/file/gfb1gmsERmQm3nu4SzPKHm/P1?node-id=97-2750&t=PQHsBsRABDTrVPfk-0.

Initial Design:

Our initial idea for a game title was “Self Aware”, since players would have to become more self-aware as they 1) learned what other players thought of them and 2) selecting the card that they think fits them the most. We decided to go with a flame motif because of the idea that players would “burn” each other with their honest assessments of each other during the game. In addition, some of our cards were pretty provocative, so we wanted to lean into that idea more in the visual design.

We decided to go with a pretty minimalist design for the cards. We decided to left-align the text at the top of the card in order to make the text more visible when players fanned out the cards in their hands. We also added in a small flame icon in the bottom right to help players identify which deck the cards are from, which would also be useful when sorting the cards back together.

Iteration #2:

After asking for feedback on our first iteration, we received feedback that the title and description of the game seemed somewhat disconnected from the flame themes. We also received feedback that the card decks could be difficult to distinguish from the back for colorblind users, since the only difference was the flame colors.

As a result, we decided to change the name of our game to Hot Takes, to better link the name of the game to the flame imagery and color scheme of the game. We also added the deck label to the back of the deck, to make it more accessible for people with color-vision deficiencies. Finally, we decided to change the “spiciness” markers on the lower corners of the card to also vary with the number of flames, rather than just the flame color– similar to how spice markers in restaurant menus work– to further enforce the spiciness metaphor.

In our final iteration, we updated the box description to match the new title (removing references to self-awareness and instead adding wording relating to “hot takes”), and also added images of sample cards to the back of the box to give potential players an idea of what they could expect from the game.

Final Prototype

Print n Play: Hot Takes Print n Play

Final Mockups:

Instruction Manual:

Cards:

Physical Prototype: