Spyfall

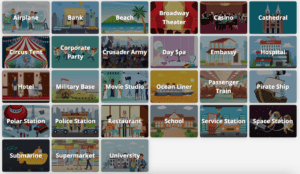

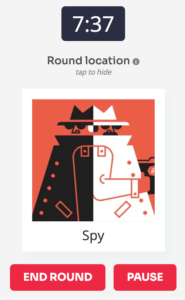

For my first critical play, I played Spyfall with some friends (5 of us total). Spyfall was developed by Alexandr Ushan in 2014. It is originally a card game, but has been transformed into online versions such as this one. (https://www.spyfall.app/) Spyfall seems to have a broad target audience, but the card version of Spyfall advertises its target audience to be at least 13 years of age. I’d say this is a fair assessment even for the online version, because the game requires a fair amount of lying and deception, particularly if one is assigned the Spy role.

Though I appreciate how accessible the game is because it can be played online, I think playing in-person would be significantly better than playing on an online platform because playing in-person adds to the tension and excitement in the room. Over FaceTime, which is how I communicated with the rest of the players, it’s difficult to read others’ body language (e.g. fidgeting if they’re lying about being the spy, constantly checking one’s card to see their role in a particular location). Playing together in person would make these behaviors easier to notice, and potentially add to the spontaneity of the game since there would be more of an effort to deceive others successfully.

How the formal elements of Spyfall contributed to the fun of the game

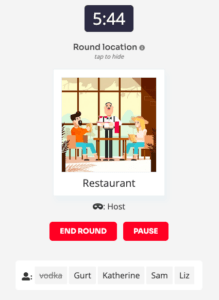

The ability to decide one’s own display name in the game supports one’s personal expression, because players really tap into their personalities and past experiences to inform how they present themselves in the game. Every round, players are assigned a specific “role”, e.g. “lifeguard” at the Beach or “unwanted guest” at a Corporate Party. It’s up to the players how much they stick to this role throughout the game, but it’s usually more interesting when players ask questions that are directed towards them, from the perspective of how someone in their role would answer (i.e. what would an unwanted guest do at a corporate party?). I also enjoyed seeing the names that people gave themselves in the game (which seems to be exclusive to the online version), since they had the opportunity to express their personality and character in that regard, as well. For example, my friends and I used names or nouns that weren’t our own to confuse each other, and exclusively referred to each other by these names throughout the game which was hilarious.

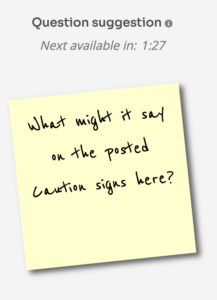

Since the game is dependent on the generation of insightful questions which will help reveal who the spy might be, it can be a lot of pressure to come up with a good question. At least in the online version, players can scroll to the bottom of the page to see example questions that are usually good candidates for interrogating other players. I think this element of the game is important to making the game fun, since good questions are what allow players to experience discovery — each question peels back a layer of whether or not someone is the spy, since good, specific questions can leave the spy stumped and want to resort to vague answers.

The objective of the game is to outwit other players — for non-spies, the goal is to outwit the spy and correctly guess who it is; for the spy, the goal is to outwit the other players and guess the location before they’re sought out. I believe this is the primary formal element which contributes to the fellowship of the game, since players will work together to determine who the spy is. For example, in my specific plays of Spyfall, it was funny to see how quickly the multilateral competition structure shifted into a unilateral competition structure once someone had a suspicion on who the spy might be. In one of the rounds, my friend Anika was the spy, and our location was a Diamond Mine. When I asked her, “Do you get a lot of sunlight here?” She responded with an emphatic, “Absolutely,” which pretty quickly signaled to me that she was most likely the spy. From that point forward, my other friends were confused by her answer as well, so they started to build a case around why she might be the spy of the round. I find it interesting that Spyfall seems to employ two different structures of competition — there’s a great deal of freedom in how questions are generated and to whom they’re directed towards, and this is directly what impacts this shift.

I like how quick a game of Spyfall can be, and how easily new players can be incorporated into the game. Replaying Spyfall over and over again, however, would make it less fun because there’s only so many locations to guess, and it can be hard to think of questions that haven’t already been asked before, after several rounds. Each round is distinct because the spy is different in every round, but after a while, it’s fairly easy to scope out a spy and team-up against who the majority suspects.

Other games in Spyfall’s genre

Spyfall reminds me of a simpler, lower-stakes version of Mafia, since players are also trying to outwit others in Mafia. However, there are a number of differences between Spyfall and Mafia that greatly affects the dynamic of the game. First, Spyfall is more consistent in terms of duration, as each round is strictly 6-10 minutes, whereas with Mafia, a game can take anywhere from 10 minutes to 30 minutes. It could potentially take longer if every person in the room was a Professional Liar and if there were a lot of people (15+). Next, Mafia employs narrative to progress the game forward, as there is usually a moderator that comes up with fictional stories and background context as to how a civilian was killed in each round. On the other hand, Spyfall is entirely directed by the person asking the question. In this way, without sufficiently specific or interesting questions, the game quickly becomes very bland. Lastly, though Spyfall and Mafia both support a sense of expression and game as self-discovery, playing into a character’s role feels more optional and laid-back in Spyfall, whereas in Mafia, playing the character one has been assigned is crucial to create a fun and successful game. This has its upsides and downsides, however. Spyfall distributes roles quite equally, as everyone is responsible for asking and answering questions, whereas in Mafia, it’s easy to be a passive player if assigned a civilian role, since there’s not much one can do besides wait until the next time the crowd votes out a certain person.

Moments of particular success or epic fails

For my friend Anika, it was her first time playing Spyfall. In the first round, she said, “I can’t see anything on the screen, is it loading for you guys?” to which my other friend, Molly, who has played Spyfall before, responded with, “It’s because you’re the spy.” Anika actually believed Molly, which was really funny because it turns out Anika’s browser just crashed, and she literally couldn’t see anything on her screen, not because she was the spy. That game ended pretty quickly.

In one round, I was so sure that my friend Molly was the spy because of the way she was vaguely answering questions and the tone with which she was responding. When I made the case for why Molly was the spy, I referred to past questions I had asked her and her responses that she gave. While recalling these events, however, it must’ve given too much away because Elizabeth, my friend who was actually the spy in the round, guessed the location correctly. We felt defeated. 🙁 This made me realize that in the same way that a spy can be preoccupied with trying to cover up their identity, non-spies can be so preoccupied with trying to figure out who the spy is that they can ask questions or answer in a way that is too revealing of the location without them even noticing. In this instance, I was a little too specific with my recall of my questions and Molly’s answers, that it gave Elizabeth time to figure out the location and defeat the rest of the players.

How I’d redesign Spyfall

I think one of the most attractive features of Spyfall is how independent it allows players to be. Players come up questions themselves, in what order they’ll ask others questions, and who to direct the question towards. The downfall of this, however, is that for newbies, it can be challenging to generate questions that are unique enough to differentiate between the spy and the non-spies but not so unique that it gives the location away. Additionally, if a newbie is the spy the first time that they’re playing, not only will they have to worry about giving away their identity, but also coming up with questions to ask others, as well as acting as if they aren’t the spy. This is a lot of pressure — so much so that these factors are exactly what can lead to vague, bland questions and answers that don’t progress the game. With this in mind, the first thing I’d change is more strongly enforcing a rule such that players play into the role they’ve been assigned. For example, in past rounds, I’ve been assigned the role of “beach photographer” when we were at the Beach location, or the “host” at a Restaurant location. When my friends and I played, I was answering the questions as Jeong — not as a beach photographer or a restaurant host. Getting into these characters would add more excitement and decrease the probability of vague and bland answers throughout the game, since we’d now be more attached to the role that we play in the narrative of seeking out the spy. The second thing I’d change is by creating a time-limit on how long a player can take to answer a question, and ensuring that players answer with a strict “Yes” or “No”, instead of “Maybe”, or “Sometimes”, or “Personally, I wouldn’t”. When a player expands on their “yes” or “no” response, it is extremely helpful and creates a more playful atmosphere, but when a player answers vaguely, it doesn’t add an element of fun to the game. Enforcing a new structure to the responses leaves less room for ambiguity and a rapid-fire question and answer setting which generally tends to be more amusing than unlimited time to ask and answer a question. Third, I’d change the minimum number of players to be at least five or six, but encourage players to play in larger groups, since a game with any less leads to a very quick turnaround and almost no challenge to guessing the location and/or the spy. Lastly, I’d add more spies to the game depending on how many people are in a round. For example, if there’s only four players in a game, one spy makes sense. However, if there’s ten players in a game, having two or three spies would make the game much more interesting — similar to how the number of Mafia members increases with the number of players in Mafia, Spyfall could implement a similar change. This way, spies can bounce off of each other to create confusion among the players, and there is a higher sense of urgency since there’s more people to ask questions and less time to do so.