Gone Home

Available: Mac, Window, Linux, Epic, Nintendo Switch, iOS, PS4, XBOX One

Designer: Steve Gaynor

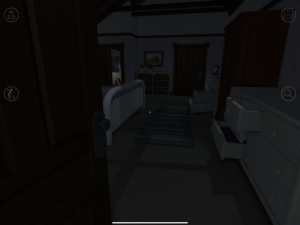

This game was incredible at setting an eerie atmosphere. It was not necessarily a scary game, but I found myself constantly anticipating something bad happening. When I was younger I actually lived in a dark old creepy house like in this game, and it did a great job at simulating what it felt like being home alone on a dark and stormy night in a house like that. I found myself doing similar things that I would do in real life to feel comfortable in the game: turning on all the lights, putting on music, and staying in the teenager’s room. It was interesting to realize how the mechanics of the game actually made it scarier. In real life – you have peripheral vision and other senses at your disposal, however in this game you relied on a limited field of sight. This caused there to be multiple times throughout the game where my heart genuinely skipped a beat because loud thunder cracked out of nowhere or the house creaked making it sound like there was someone walking around behind me.

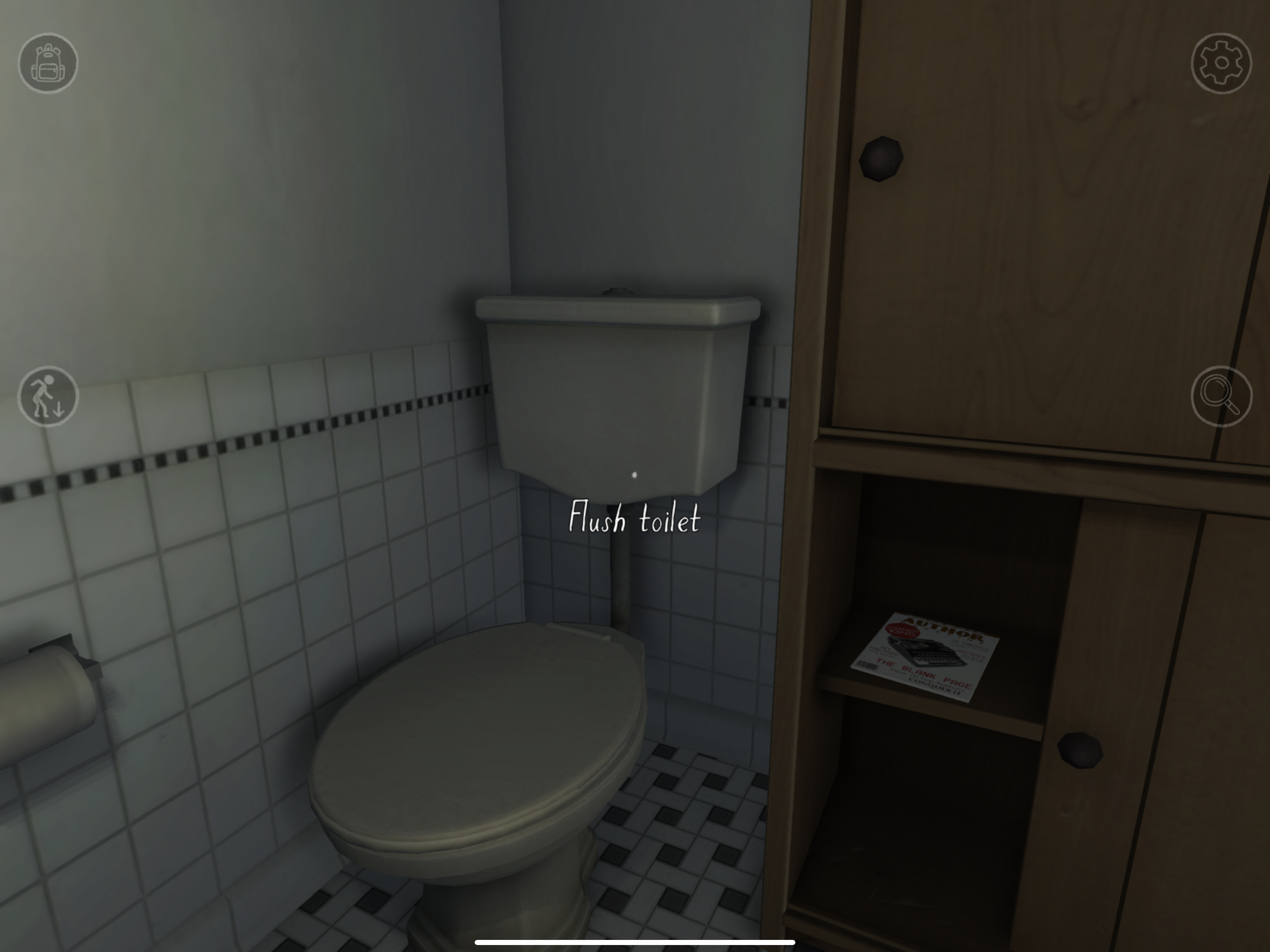

I think it was particularly interesting to play this game in the context of setting up my own escape room. Especially because in class we learned that Escape rooms should not have anything items that aren’t relevant to clues because players will spend too much time assuming it’s useful. I didn’t finish Gone Home, but from the hour of game play I did, there were a lot of useless items you could interact with. For example, every toilet and sink was interactive. Flushing the toilet or turning on the sink were not relevant to the mystery but I spent a lot of time trying to see if there was a clue I was supposed to clean off in the sink because they were interactive. Perhaps the abundance of interactive objects is fine here due to the lack of time pressure. Unlike escape rooms, there are no penalties in this game at all, so perhaps the game designers were ok with adding objects that could cause players to go down a useless rabbit hole since they have all the time in the world to explore the whole house.

I hope to learn from how the game gradually builds up the player’s knowledge from nothing. The game is designed so that you only know what you have discovered. So in the beginning you can’t see a full map of the house and don’t have any clues, and all you can do is focus on finding a key. From there you gradually build up your knowledge of the house and the family. By the end of my game play I was able to piece together the parent’s marital problems, Sam and Lonnie’s relationship (queer icons!), and Sam’s dynamics of hiding things from her parents and wanting independence. It’s interesting to think about how to translate the initially constrained perspective to a physical escape room, perhaps only certain puzzles should be visible in the beginning. I really like the use of letters as clues in the game. Different mechanisms provided me unique information about the letters. Sometimes they were highlighted, crumped up in the trash can, or hidden behind a hidden panel. Each of these told me different things about the content that I should pay attention to on each letter. This game also did a good job of utilizing different locks. It became evident that the attic was the final lock I would need to open to finish the game. However, in order to get there, there were a series of other locks I would have to open first. In our escape room, we want similarly sequential game play. So perhaps we can employ some of the mechanics in this game where items needed for the final lock lie behind smaller locks you must open first to ensure players work on puzzles in the correct order.