Artist Statement

The ultimate goal of “Likely Story” is to promote fellowship and create an opportunity for players to get to know one another. When each player takes turns acting as the storyteller they engage in expression–they reveal elements about themselves to the other players. The option for the storyteller to attempt to fool the other players adds an additional dimension of fellowship. The other players are pushed to study the storyteller more carefully to determine whether the story is thought to be in line with their judgements. During the questioning period, the other players are faced with a challenge–to figure out whether the story is true or not. During this period the players are also actively engaging in fellowship–where they work with other players to ascertain more information about the storyteller and judge whether the storyteller is being truthful. Thus, the ultimate goal of “fellowship” is embedded and achieved in “Likely Story” through multiple avenues.

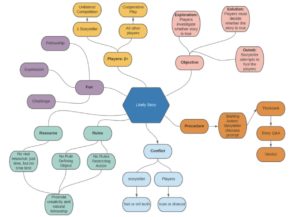

Concept Map

Initial Decisions About Formal Elements and Values

In designing our first prototype, we wanted to cultivate both lighthearted and intimate moments of storytelling without pressuring players to reveal more than they wanted to. And we wanted to explore how ambiguity and deception (fun as narrative) can cultivate curiosity and authentic connections (fun as fellowship).

Our initial decisions on formal elements then focused on how to build fun as narrative and fellowship. It was important that both types of players, (the Storyteller and their interrogators) could always be playing and interacting altogether, and that it wasn’t only fun to be the Storyteller. The game is technically a multilateral competition, but a round plays out in unilateral competition. Because the Storyteller cycles from round to round, this mitigates the “us vs. them” feeling felt by unilateral competition. And yet, the moment-to-moment gameplay directs attention away from the multilateral competition because all of the listeners have to come to a consensus. This interplay allows us to have fun competition without it seeming overwhelming or giving too much emphasis to scoring and the original outcome of highest point total.

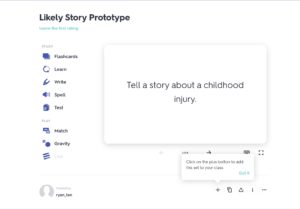

Our key objectives are that the Storyteller wants to fool the other players, who are trying to guess if a story is real or not. Our defining rules were the “Tell a story about…” cards. We spent a lot of time considering what prompts would lead to organic and consensual storytelling, and we came up with a first set of cards that were enticing but with plenty of room for ambiguity and invention. We wanted the thought behind the prompts to do the fun-making, so we used minimal resources as we thought they would draw attention to the game components and not players’ intrinsic tools and strategies.

Similarly, we wanted minimal structure in the procedure (basically just 3 steps), enough to keep the game moving but to let players take advantage of their own strengths. We decided to use nudges rather than enforcing what happens at what time: our original wording encourages to “interject” and “pressure” at any time. Lastly, we wanted to use conflict as an impetus for narrative-making and connection, and not to aggressively inspire players to beat other players. In line with our initial values, we aimed for the Storyteller and their interrogators to depend on each other to achieve their goals, so it feels less like weaponized questions and lies and more like players all uncovering a story up together.

Testing and Iteration History

Ideation

We started by formulating ideas on Mural. We each wrote our ideas on sticky notes, grouped similar ideas together, and voted on the most appealing idea.

We settled on a couples game that would involve partners guessing whether a statement is true.

Checkpoint 1

We submitted this version of the game for checkpoint 1, but we were still uncertain about how to balance the line between intimate and casual fun for a couple’s game.

The main feedback we got was that it would depend on the questions we choose, and it was mostly our decision to make. We needed to decide the best course of action, and we thus decided to do a team brainstorm session.

Team Brainstorm

We decided to brainstorm on the sort of questions we could ask for couples. However, in the process of coming up with a set of questions, we decided to change the target audience of our game.

This is because we wanted the scope of the players to range from strangers who just met to people who know each other well. In line with providing a fellowship aesthetic, we felt that providing a game that is playable by people who just met in addition to people who already know each other has a greater magnitude of fellowship. Getting to know a stranger through a game serves as an ice-breaker, and reduces awkward silences that otherwise occur in normal scenarios. The “magic circle” provided by the game enables players to be more relaxed in sharing about themselves and learning about each other as they are protected by the boundaries of the game even though they might still end up sharing intimate information. Moreover, a lot of tension is created when strangers play since it is harder to gauge whether someone you don’t know is telling the truth. Similarly, the release of tension as people who don’t know each other keep sharing and learning about each other provides a greater sense of satisfaction than when players who have known each other for years try to fool each other.

Ultimately, changing our target audience was the best way of establishing fellowship among a larger audience. A couple’s game would not only limit the number of people who can play (limited to 2 players for most of the couple relationships) but would also limit the kind of questions we could ask since we would have to be sensitive to the nature of couple relationships, and the kind of questions that would still provide fellowship type of fun. In addition, we wanted our game to be playable in different contexts: at pre-games, at the end of parties, at get-togethers, thanksgiving dinners, and many other occasions.

Results of The Team Brainstorm

Our brainstorm session resulted in the game roughly described in the figure below:

The game allowed for as many players as the cards could permit, and the players would face each other in a unilateral competition in each round. The other opponents would create the conflict in each round as they try to apply pressure on the story teller by asking questions that would possibly expose an inconsistent answer and easily highlight whether a story is made up.

The procedure was simple:

- Player picks a card that tells them whether to tell a true story about a given card prompt.

- The opponents would guess whether the story was true

The objective was to outwit opponents, and the outcome was the number of cards players have at the end of the game.The winning condition was to have the most cards at the end of the game.

The game had the following rules:

- Players have one minute to tell a story

- Opponents have one minute afterwards to ask questions

- Opponents questions are limited to yes or no questions, and can only use present tense

- Opponents have 10 seconds to give the verdict

- The game ends after each player has told a story

- After each round, the players can use cards with a different level of difficulty

- The player keeps the card if the opponents couldn’t make the correct guess, otherwise the card is discarded

- Cards are chosen in random from a set of cards depending on a chosen difficulty agreed by the players

The card prompts were chosen in a progression of easy questions, medium questions, and hard questions. For instance, an easy prompt was something like “Tell a story about you involving your childhood -TRUTH”. The prompts get harder when the storyteller is limited to a word that would be harder to formulate a story with such as “Tell a story about your experience with a kangaroo – LIE”. Having difficulty progressions in the cards was to contribute to the challenge aesthetic. The players had a choice whether to increase the difficulty, and thus had control of how intense the game would be. This provided the option of having a playful game just meant to share stories in a less serious competition, and the extreme end where players have the hardest prompts and have to work really hard to win. Leaving this choice to the players improved the players expression as they had control of what kind of game they would play.

This version of the game utilized time as a major resource ensuring the storyteller was pressured in telling the story in a short time with no time to brainstorm. Similarly, the opponents had very little time to interrogate the storyteller so they had to choose their questions wisely, in addition to an even shorter time to come up with a verdict whether the story was true. The time aspect provided a deep challenge aesthetic that we wanted to achieve in this version of the game.

The game had players team up to ensure the storyteller doesn’t win the card as that was a key component in ensuring fellowship was achieved. Players had to work together to determine whether the story was true. In addition to the interrogation, they had to convince each other to make a vote. This was important since if each player were to make their own vote, the game would mostly be a challenge and wouldn’t achieve as much fellowship as we had intended.

In our own opinion, this was the best version of the game but we were the designers so we had to leave it to the playtesters feedback to affirm our assumptions.

Playtest 1

We had our first playtest in class. During this playtest, the main clarification players needed to play the game was on how to earn points. We had to explain that a storyteller earns points by outwitting the opponent, and keeps the card as score. The players were then able to play the game after the clarification as the rules were clear, and the procedure was simple.

We decided to play a round where each opponent votes on their own (more competition based), and another round where opponents come to a consensus for the vote. According to the feedback, players enjoyed the group discussion when coming up with a group consensus. This achieved the fellowship we intended and thus we affirmed that we had made the right choice in determining how to come up with a verdict.

The players also provided feedback that they greatly enjoyed interrogating the storyteller. We were happy that we had achieved the fellowship we desired as this portion of the game forced players to engage with each other to come up with questions, in addition to engaging with the storyteller by trying to pressure them to be inconsistent in their answers.

Even though we assumed that a minute was short, some players struggled to come up with a story in time. We thus decided that we would restructure the procedure to account for initial player brainstorm of the story.

Moreover, players kept choosing the easy cards and thus reaffirmed that the fellowship fun in a playful atmosphere with easy stories was more important to them than having difficult cards. This influenced our choice of cards moving forward as in the end, the main aim of the project was to provide fellowship. We thus decided that we would keep the prompts simple, and eliminate the progression.

In addition, we playtested with having the prompts tell the player whether to lie, and with prompts that let the players decide whether they would lie. The feedback we got is that players greatly enjoyed the latter and we attributed that to the sense of expression. Players enjoyed having control of the decision to lie than being restricted by the cards. We thus decided to adopt the players recommendation.

In hindsight, maybe a different group would have enjoyed the difficulty progression, but for such a small project time, we had to stick to a decision and move on.

Another major issue that came up was in the starting procedure. Players didn’t know who should start and what sequence to follow. We decided to address this by employing a Cardmaster in the game. The players would have to choose who the Cardmaster would be, and that allowed them to control a key aspect of the game. The Cardmaster would then be the one to pick cards on behalf of players, and decide the game flow. After each round, the players could pick another Cardmaster and play again.

Results of Playtest 1

Playtest1 changed a lot of things in our game that would make it to the final version. We decided to adopt the changes since we had several playtesters, and we were lucky to have multiple playthroughs to test different aspects. We were thus confident that the changes were necessary.

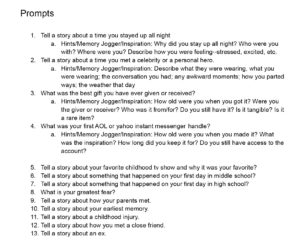

The playtest informed the decision about the prompts where we now had easy and uniform open-ended prompts as shown below:

We also had to update the procedure and rules to reflect that the game would be playable via Zoom

We made the cards on Quizlet:

The procedure was now:

- Choose one player as the designated Cardmaster

- Have the Cardmaster share screen of the Quizlet

- The Cardmaster interacts with the card on behalf of the players, reads the card aloud on behalf of the player, and the chosen player decides whether to tell a true story based on the prompt

- The other players would guess whether the story was true or false

The objective was to still outwit opponents, but the outcome was now the points players have at the end of the game.The winning condition was to have the most points at the end of the game.

The rules then became:

- Players take time to brainstorm (less than one minute is recommended but a player can take as long as they need)

- The player has to commit whether they decide they are going to tell the truth

- Opponents can interject with questions and ask for more details as the player tells the story

- If the player fooled everyone, they get 2 points

- If the opponents guessed correctly, they each get 1 point

Checkpoint 2

For the checkpoint, we submitted our refined version of the game.

We got feedback about scoring judging games which is by keeping the card, and that was great for our game. In addition, we got feedback that it was important to balance the guessing and point system of the game, and to determine a win or lose situation that ends the game.

We had to revert to keeping the card as a form of scoring since we initially had it but changed it because we would be playing on Zoom. However, by introducing points, we had added complexity to the balance of the game since each opponent gets a point if the player loses. We thus decided to stick to the player keeping the card if they outwit the opponents.

We ended up utilizing this feedback in implementing a way for the game to end when a full round is played, but ultimately our game allows for players to play for as long as they like.

We also got feedback about what kind of story to use as it was pointed out that a story with conflict and stakes would provide better prompts.

We had to brainstorm how we would introduce stakes.

Playtest 2

For our second class playtest, we decided to playtest with time pressures again as we weren’t sure if it was the right move to remove them (the current version of our game had minimal time pressures). We playtested with 1 minute, 3 minutes. and 5 minutes for the story and interrogation parts.

The feedback we got suggested that the time pressures now made the game less enjoyable as the players wanted more time to discuss amongst themselves, in addition to more time to hear the story.

We were now firmly inclined to completely remove the time pressures. As designers, we understood the value of having time pressure and the difficulty it introduces to the game. However, at the end of the day, we make the game for players. Even though we were playtesting with a select group of people (who would be the audience for this game), two different playtests yielded the same result — players didn’t want the time pressure. They valued the interaction more than the competition, and the fellowship more than the challenge. They wanted to hear the full story for as long as it would take, interrogate for as long as it would take, laugh, debate, argue, and convince each other. In the end, they would come to a consensus when there was nothing left to be said, and it didn’t really matter whether they lost or the player won. They had achieved the fellowship fun that they valued in the game. This was a major decision, but we decided to give the players what they wanted. This decision informed the final version of the game.

Results of Playtest 2

We decided to eliminate the time pressures since the playtest feedback from two different test groups (which is approximately half the class) suggested that players enjoyed fellowship more than the competitive aspect of the game. They didn’t care much about the points, but rather were focussed on getting to hear the stories, interrogating the player, trying to discuss what questions to ask, and coming to a consensus.

The main fun we promised was still achieved by this version of the game so we decided to stick to it.

Playtest 3

For the third class playtest, we decided to let the players play without any involvement of the team members. This was to ensure the game was playable.

The players used the rules doc we had provided, and were able to play the full game on their own.

One part that was unclear was how the Cardmaster would pick the next player, but they still managed to progress through the game. We decided to address this by adding a section that would have the best liar be the person to start. Our rationale was that this was the first interaction the players would have with each other. Even before the game started, this process establishes stakes. Someone who boasts that they are the best liar would now put a target on their back as they would have to prove themselves right, while everyone else would want to disprove them. Albeit a small procedure, this would introduce the much needed challenge that for the most part was now eliminated as it introduces stakes. We had found our way to introduce stakes without changing the questions that the plays already enjoyed.

One player was curious about keeping track of the time since we had relaxed time-frames for how long the activity should take. However, most of the players did enjoy the lack of time-pressure so we still didn’t have enough reason to reintroduce the time pressure. This was the final assurance that indeed, our game wasn’t supposed to have a time-pressure.

Final Playtest

This was the final class playtest of the submittable game. The game would not be changed at this point, and the decisions and results of playtest 2 combined with the minor introduction as a result of playtest3 made up our final game.

The playtest was recorded to be submitted with this final documentation, and is available as our playthrough video in the section below.

Final Prototype

The full game can be played on zoom using the linked rules below:

We are using flashcards for the zoom version, which can be found here:

The playthrough video can be found below:

Design Mockups

The design mockups can be found at the link below:

We went for a simple design to reiterate the simplicity of our game. The main intention was to signal that our game focusses on a simple and playful atmosphere of fellowship as opposed to a serious challenge. We had steered so far away from our initial design, but we ended up with a product that the players desired.