For this Critical Play, I played One Night Ultimate Werewolf on netgames.io with two other people.

Formal Elements

Players

This game is designed for three to five players, separated into two teams: Villagers and Werewolves. Only one of the teams may win; it is a Team Competition. However, there could be no werewolves at all; in that case, everyone is on the same team, although they do not initially know it. When this happens, the format is still Team Competition–the players all compete for the Village team without knowing that there is no opposing team.

Objective

The objective of each team is to outwit the other team. If there is at least one werewolf, the werewolves win if no werewolves are killed; the villagers win if a werewolf is killed. If there are no werewolves, everyone wins if nobody is killed, but everyone loses if anyone is killed.

Outcome

This is a zero-sum game; all players on one team win, while all players on the other team lose.

Boundaries

We played One Night Ultimate Werewolf on the computer; its magic circle extended to the three players, our computers, and the space around us.

Resources

The main resources are time (there is limited discussion time to decide who to kill, and each role has its own chunk of time to act) and roles (which can be switched, and which dictate the actions available to you in a round).

Procedures/Rules

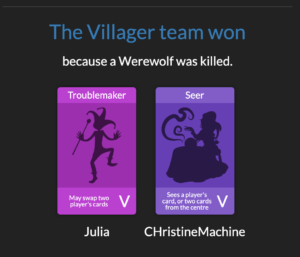

- Setup: There are six possible roles (shown in Fig. 1 and described in Step #2). Each of the players is randomly given one of the roles, leaving some roles unused. Each player secretly views their role. Nobody yet knows what the unused roles are, or what the other players’ roles are.

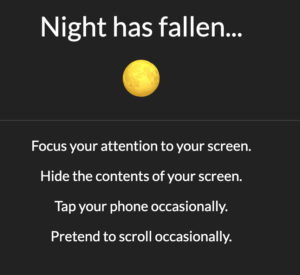

- Then, night falls. Each role gets its own turn to act during the night. When it is not their turn, players simply wait (Fig. 2).

-

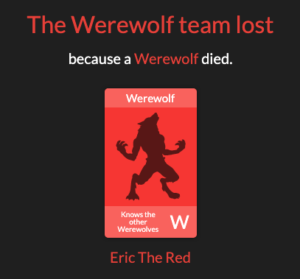

- The werewolves act (“wake up”) first. Each werewolf does nothing except view who the other werewolf is (if there is one).

- The werewolves go to sleep and the Seer wakes up next. The Seer may view another player’s card, or view two of the unused roles.

- The Seer sleeps and the Robber wakes up. The Robber may switch their own role with any other player’s role, or do nothing. If they decide to switch, they will see their new role, but the player with whom they switched will not know the switch has occurred.

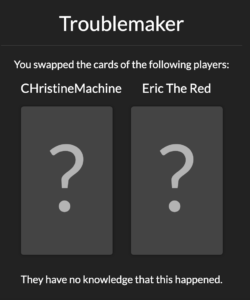

- The Robber sleeps and The Troublemaker wakes up. The Troublemaker may switch two other players’ cards. The other players will not know this has occurred (Fig. 3).

- The Troublemaker sleeps and the normal villagers wake up. Normal villagers do nothing.

-

- Day breaks and everyone wakes up.

-

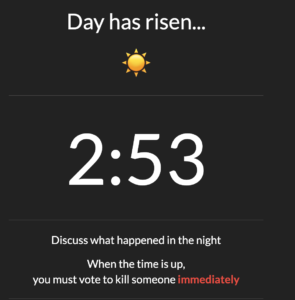

- Players discuss who they think the werewolves are (Fig. 4). They may reveal or keep hidden whatever information they want.

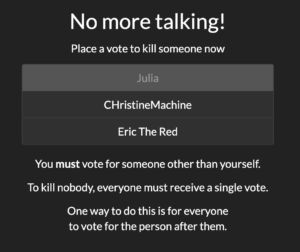

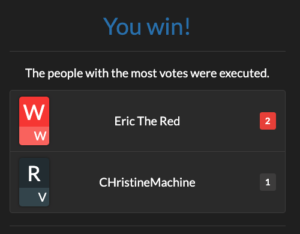

- After 3 minutes, they will be forced to vote on who they think the werewolves are (Fig. 5).

- They can skip to the vote at any time before the three minutes expire.

-

- The players vote on who they think the werewolves are.

- After the vote, the winning and losing teams are revealed (Fig. 6-8).

Fun and Improvements

Two impactful mechanics of this game are that (1) players work in teams, and (2) players do not know for sure who their team members are until all players have voted.

These mechanics create an interesting dynamic wherein players must cooperate with their team members without knowing who their team members are. Thus, secrecy creates an obstacle to team cooperation. This gives rise to the Challenge aesthetic (because of the obstacles) and the Fellowship aesthetic (because of the team dynamic). I think the fact that players must work to determine who their team members are makes the Fellowship aesthetic especially strong, as team members feel that they earn each other’s trust.

Another mechanic of this game is that players have different possible actions that correspond to their roles. For instance, the Robber “robs” another player’s identity, while the Seer “magically sees” another player’s identity. The players’ objectives also correspond with their roles: villagers want to kill werewolves, while werewolves aim to not be killed. The fact that the actions make sense with the roles strengthens the Fantasy aesthetic of the game, as players feel that they are actually acting out their roles with their actions.

These character roles, in addition to the structure where characters wake up at different times during the night and then discuss together in the morning, create a strong Narrative aesthetic. One game of One Night Ultimate Werewolf tells one story; while playing, I enjoyed thinking about the story, and I was invested in the outcome.

One concern I have is that this shortened version of Werewolves removes the werewolves’ ability to kill a villager during the night. This makes the game a bit less interesting for the werewolves. It also slightly weakens the Narrative aesthetic–why are the villagers killing the werewolves if the werewolves haven’t killed anyone?

Perhaps this could be fixed by allowing the game to occur over two nights instead of one. This would allow the game to remain shorter than the normal Werewolves game, but would allow the werewolves to act at least once.