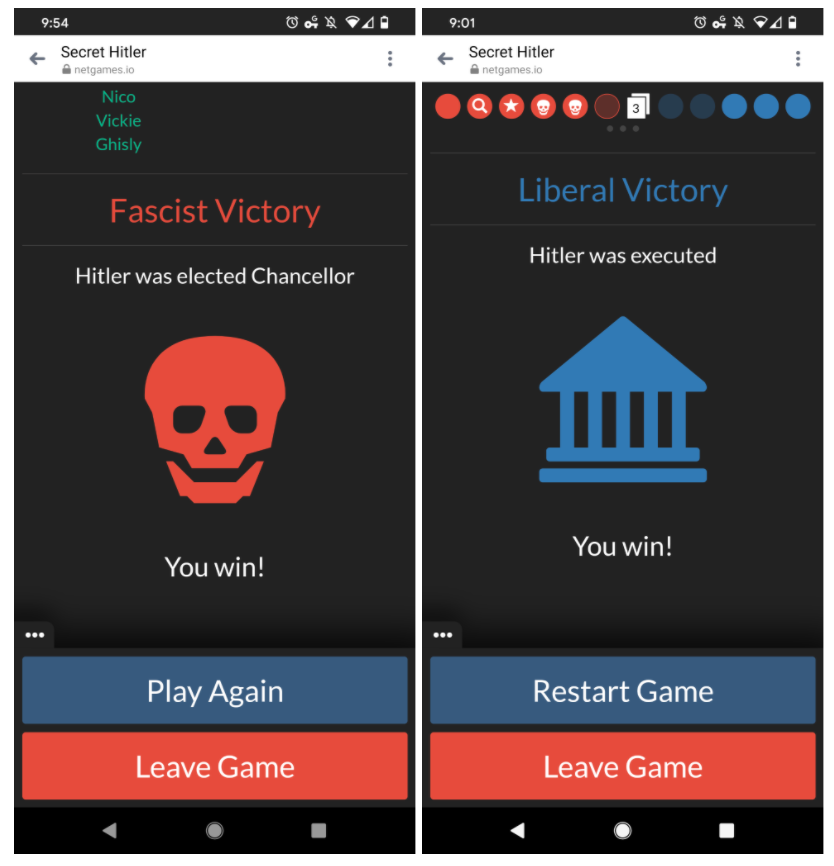

This week, I played Secret Hitler online with 7 friends across two states. We get together to play Among Us frequently and were nervous to try a game only one of us had played previously, but it ended up feeling worth it. We played longer than expected (4 rounds!) and laughed like crazy. It was fun for us to accuse each other of being fascist, suspicious, and fishy. We look forward to playing together again.

While we hope to one day play in person, this time we used the online version on netgames.io/games/secret-hitler. Some of us were on phones and others were on laptops. We connected over Zoom to play. Three of us played in the same physical space as another player (two couples and one single player). The player that had played the game previously read out the rules as presented on the website before we started to play. Most of the rules went over our heads so we decided to play and learn as we go.

About the game

Secret Hitler is a hidden identity social deduction party game developed by Goat, Wolf, & Cabbage LLC and manufactured by Breaking Games. Max Temkin, who created Cards Against Humanity, is one of the designers. The game is targeting people who enjoy provocative games and likely reflect the identities and interests of the designers (e.g. 30 somethings). It may also target fans of Cards Against Humanity as Temkin initially launched the concept on Kickstarter to generate funding in 2015. They successfully raised over $100,000 (twice their goal) in less than 24 hours with support from 30,000 backers.

Players & Objective

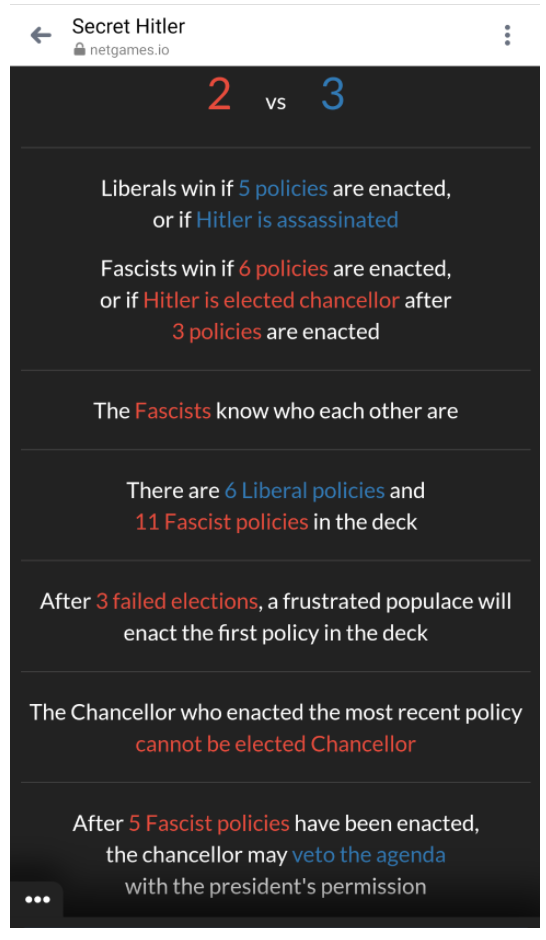

The game is designed for 5-10 players who are broken out into two teams: Liberals and Fascists. One player is assigned to be the “Secret Hitler.” The liberal team’s objective is to prevent the Fascist regime by finding and stopping the Secret Hitler. The Fascist team’s objective is to crush the Liberal regime by supporting and electing Secret Hitler. Identities are secret, except for the Fascist team who gets to see the identities of other fascists including Secret Hitler. This makes the game interesting because it requires players to investigate and deduce who they can and can’t trust.

Rules and Procedures

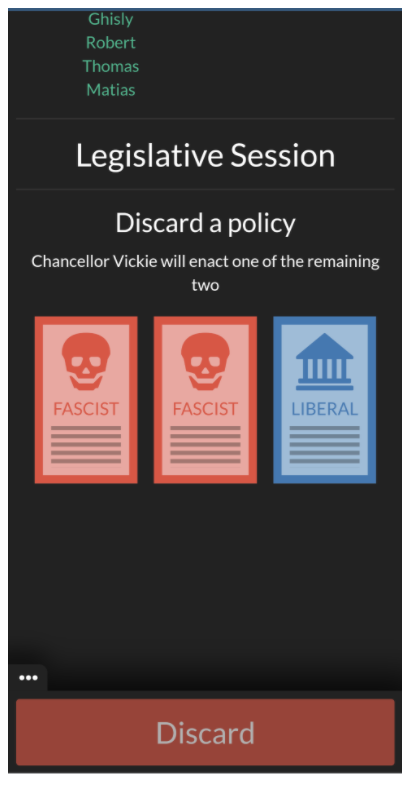

In short, the game revolves around the enactment of liberal and fascist policies. Players take turns playing the role of the president each round in an ordered fashion. The role of the president is to nominate another player as Chancellor. All players then choose to vote “Ja!” or “Nein!” to approve or veto the nomination. If the election goes through, the president gets to choose two out of three random policy cards to hand over to the chancellor. The chancellor then picks one of the remaining two policy cards to enact. Players are under scrutiny for their choices, as fascist policy plays are seen by the Liberals as suspicious. There are 6 liberal policy cards and 11 fascist policy cards in the deck at the start of the game. Presidents can investigate a player’s party membership, check the three top cards of the deck, assassinate a player, or choose the next round’s President after passing a fascist policy. The game ends when five liberal policies or six fascist policies have been enacted, with the respective party winning the game. There are also two alternate paths to winning. Liberals can win if Hitler is assassinated or fascists can win if Hitler is elected Chancellor.

Critical Play

Overall, I’m not surprised by the game’s popularity. It certainly delivers on its promise to entertain a group of 5-10 players.

The biggest pain point we experienced was the learning curve of learning the rules. The basic two team structure and path to winning were straightforward. However, some of the mechanics were quite difficult to wrap our heads around. For example, we didn’t keep track of the rounds well enough to know when it would be possible to try to assassinate the Secret Hitler. It was also hard to track how many failed elections happened, which triggers the effect of the policy “on top of the draw pile” being enacted without oversight by the present President or Chancellor. The online version attempts to track this on the top header, but the icons were not intuitive. We didn’t know what the magnifying glass, skulls, eyes, and stars meant, for example. Additionally, the draw pile itself did not seem to be an obvious element in the online game. Instead, players relied on the instructions on the screen for cues on the next action to take.

Another significant pain point was in the way cards were laid out and selected. The online version requires you to select one of three cards to discard, instead of selecting two cards to pass on to the chancellor. This small but significant detail resulted in a number of accidental selections by players. (It is however possible that some of the players intentionally selected the cards and stated it as an accident to create a diversion from their secret fascist identity!)

An unintended difficulty of the web version is that each player gets to select their name. Some of my friends have a habit of naming themselves with the names of other players which makes tracking identities confusing. One player named himself “Hitler” and another “NOTAFASCIIIIIST!!!” “Hitler” ended up actually being Hitler! Game designers may not expect players to not use their names, but it is interesting that some players may develop unexpected habits that add a layer of difficulty, complexity, or even comedy to the game.

It would be interesting to play the in person card game, as these challenges, with the exception of the learning curve challenge, would not be an issue in a more physical game. The web version did make it easy to visualize the order of the players, which did help quite a bit. I would imagine this could be more difficult to do in person.

One thing I would change to make the game better is to provide more scaffolding in the online version, such as a narrative overlay that explains key components of the rules at relevant points in the game. For example, it can warn players that two elections have been failed before the third election attempt. It could also let players know, once 5 fascist policies are enacted, that the chancellor can now veto the agenda with the president’s permission. In other words, there is ample opportunity to remind the players of the rules and procedures in a more contextual way to alleviate players’ cognitive load.